In my previous post, I addressed how Québec was not reinventing itself as a socialist haven. I will now attempt to show that the NDP’s impressive showing in Quebec does not indicate a rejection of sovereignty.

What does Quebec want?

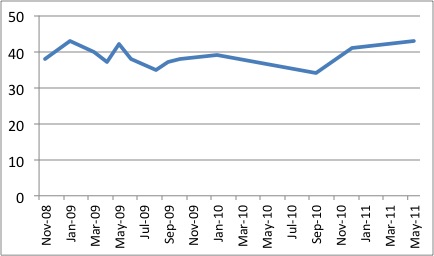

If the NDP’s Quebec surge corresponded with a loss of steam in sovereigntist support, we might expect to see dwindling numbers of Quebecers willing to vote in favor of Quebec’s separation from Canada. But is that the case?

Chart 1: In favour of sovereignty from November 2008 to May 2011

Source: CROP, Évolution du climat politique au Québec, mai 2011.

As the poll results show, support for sovereignty has not declined; in fact, in May, after the federal election, it recently climbed to its highest point (43%) in the last two years.

Another interesting fact to point out is that one in four Québec NDP voters would vote in favor of sovereignty in a referendum (as you can read in detail, and in French, here). So although the NDP is not seen as a sovereigntist party (fewer people in favour of sovereignty vote for the NDP than for other parties), it is also not seen as really hardline federalist. Accordingly, some sovereigntists feel comfortable casting their vote for the NDP because they think there is no real danger in doing so; voting NDP does not strike them as a threat to sovereignty.

Is sovereignty a thing of the past?

Some may be under the impression, that separatism is an outmoded idea, one The Economist trumpeted was “…if not dead, there are many signs that separatism has slumped into a deep coma.” But as political analyst Jean-François Lisée highlighted in his blog, the reality is not that simple.

To examine the current role of separatism in Quebec, Lisée uses as an indicator the number of persons in Quebec who identify themselves as primarily Quebecers or as Quebecers only. It may not seem directly related, but it is interesting to know that in 1980, 40% of the population of Québec considered itself Quebecers only or primarily Quebecers. In 1995, that number rose to 50% of the population.

Let’s see how it evolved in recent years.

Chart 2: Self-identification as Quebecers

(The blue line is for Quebecers primarily/only, the yellow for both [Quebecers and Canadian] and the red line is for Canadian primarily/only.)

SOURCE: CROP/Idée Fédérale et AEC/Léger

As Chart 2 clearly shows, in recent years, self-identification as primarily or only Quebecers is on the rise.

Some people from other Canadian provinces may think that they, too, have a close relationship with their province. Maybe, but not as much as in Quebec. In fact, the same study reveals that only 6% of non-Quebecers Canadians identify with their province first or only, while 67% of them identify with Canada first or only.

Identification with Quebec is not only strong among aging baby boomers, it’s even stronger among younger francophones. While 71% of total francophones consider themselves Quebecers first/only, 78% of the 18-24 youth francophone identify themselves that way.

Not only do the more obvious segments of Quebéc society say “Yes” to sovereignty (the proportion in polls is pretty stable), the “structural” identity factors also seem to indicate a growing segment of the Quebec population is open to the sovereigntist option.

So is the sovereigntist option running out of steam? Not according to the numbers. Even though a lot of Quebecers voted for the NDP, a federalist party, it is important to remember that it is in no way a sign of the end or even erosion of the “national question” in Quebec. Some could even say that the fact that the orange wave had this degree of strength only in Quebec indicates a political distinction between Québec and the rest of Canada that makes the nationalist project even more significant.

So the question remains, what does this orange wave mean for relations between Canada and Québec?

Next post: Part 3 – What does the orange wave mean?

Simon Tremblay-Pepin is a researcher at IRIS, a Montreal-based progressive think tank.

This post first appeared on Behind the Numbers.