If you’ve opened your eyes in the last two months, you’ll know that there’s a new boogeyman coming to deceive you and your family: the phenomenon of “fake news.”

The spectre of fake news has been flooding the airwaves — with a noticeable uptick since the U.S. federal election in November — and it seems to be gaining steam with every passing day.

But what is fake news? Everything from celebrity death hoaxes to political misinformation to actual reporting on public statements is now seemingly huddled under the fake news umbrella. Allegations are flying that concerted efforts to circulate fake news impacted the outcome of the U.S. presidential election — a claim made even by the director of U.S. National Intelligence under oath last week. If true, this is cause for concern.

Perhaps more concerning, however, is the vast potential for the fake news phenomenon, and the anxious hand-wringing it induces, to act as cover for justifying broad censorship powers — whether they come in the form of voluntary measures by for-profit platforms like Facebook and Twitter or, even more alarmingly, government-mandated action.

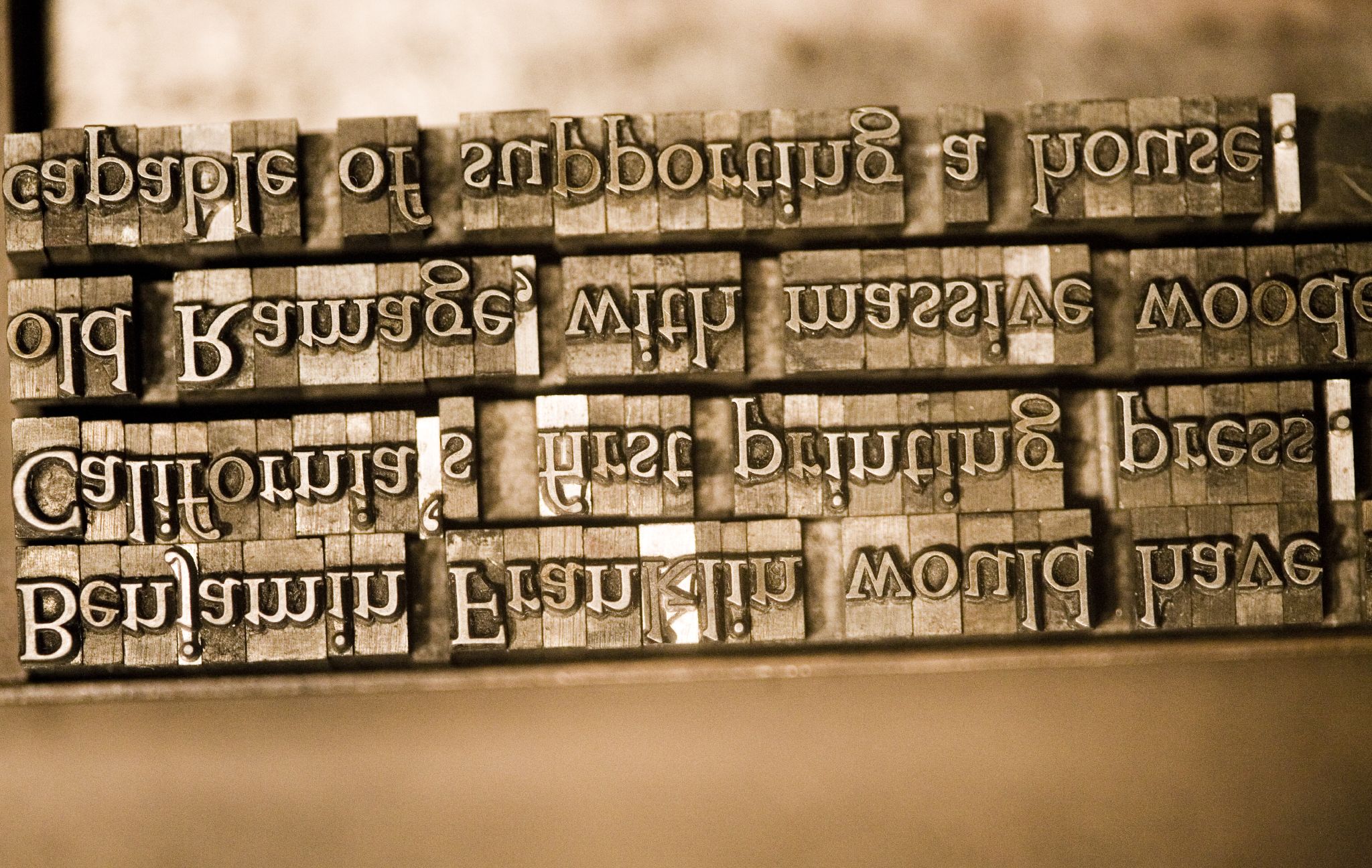

Fake news is not new

In examining the fake news phenomenon, particularly in the context of electoral politics, it has to be recognized that spreading misinformation about one’s political opponents is as old as politics itself.

After all, who can forget the spectacular political rivalry between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson in the late 1700s — hailed as the “birth of negative campaigning” — an era plagued with smear campaigns, and even a false news report about the death of a candidate.

Before we had “fake news,” we had propaganda. And before propaganda, we had gossip. And in the wake of recent events, there have been numerous articles pointing out that there’s nothing new about being misled — whether intentionally for personal or political gain, or as a result of bad reporting.

For a comprehensive history of ways we’ve been led astray, check out The Real History of Fake News by the Columbia Journalism Review.

Governments taking action

Just because fake news isn’t new, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be concerned about it. The fact is, democratic systems are designed in order to facilitate the participation of an informed populace — and the spreading of misinformation affects this.

The real question is how we define and combat the problem.

Recently, in an interview with Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, whistleblower Edward Snowden was asked about the issue of fake news. His comments picked up on a refrain we often hear echoed by free expression advocates — he eschewed the need for “referees,” saying:

“The answer to bad speech is more speech. We have to exercise and spread the idea that critical thinking matters now more than ever.”

But governments around the world are taking an approach that is about as far from this principle as possible, in many cases suggesting that new legislation is needed to tackle what they’re calling propaganda.

In Germany, chancellor Angela Merkel has suggested making it a criminal offence to publish fake news, a call quickly echoed by an Italian antitrust chief, demanding fines and censorship for those circulating fake news stories.

In the U.S., immediately following the election, Hillary Clinton came out swinging, saying that “lives are at risk” due to fake news and that “bipartisan legislation is making its way through Congress to boost the government’s response to foreign propaganda, and Silicon Valley is starting to grapple with the challenge and threat of fake news.”

Last but not least, we have Canadian Member of Parliament Hedy Fry, who has been outspoken in the past on her concern about the veracity of information found online. In early 2016, she raised those concerns in a Heritage Committee meeting, saying:

“Who is going to regulate in terms of accuracy, the digital platforms? Anyone can put anything out there and nobody knows if it’s accurate.”

It must not have been pointed out to Fry that there is nobody who regulates truth in books or magazines, either, and it was reported mere weeks ago that the same committee is looking into ways to curtail fake news.

The idea that governments everywhere are exploring legislation that, presumably, would put them in charge of determining what is “accurate” should sound alarm bells. The inherent dangers that come with giving legislators the power to decide what constitutes “truth” undermines both free expression and freedom of the press.

It’s also a system that’s ripe for abuse. Imagine, if you will, that you agree with the definition set out by the government of the day that punishes or criminalizes fake news — are you so sure that you’ll agree with that definition if and when that government changes it under future leadership?

Real journalism = fake news

Still not convinced? Let’s take a look at a real-world example playing out before our eyes. A recent controversy involving the largest police union in the U.S. sheds light on how the term “fake news” can really just mean “something I don’t like or disagree with.”

In one corner we have the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) calling foul on VICE News, among other outlets, for reporting a story based on a social media post made by the police union. The post appears to be addressed to the Trump Administration, in which a number of issues are enumerated that seem to be either policies the union supports, or requests from the union itself to the administration.

Despite the document being made public by that very union, when VICE reported it with the headline “What America’s Largest Police Union Wants,” this did not sit well with the FOP — who promptly issued a press release claiming that they had been the victims of fake news.

In the other corner, we have journalists looking bewildered. Once again, there’s nothing new with this “two sides to every story” tale. But when we have powerful organizations seizing upon a potent new threat in the mind of the public — namely fake news — and governments threatening to criminalize that same fake news, real reporting is bound to get caught in that dragnet.

Who decides is important

So what do we do about fake news? As Washington Post reporter Margaret Sullivan points out, it’s a real phenomenon:

“Fake news has a real meaning — deliberately constructed lies, in the form of news articles, meant to mislead the public.”

As it stands, there are at least two problems with the furious debate on this burgeoning issue. The first is that the term has been co-opted almost as fast as it was imagined: Ask 10 different people and you will get 10 different explanations of what counts as fake news and what doesn’t. There is nothing but shades of grey.

The second problem is the attempt by politicians to legislate around this issue. Without a clear definition of what counts as “fake” and what is “real”, attempts to create policies that punish fake news or its creators will at best alienate vast segments of society who disagree with the proposed definition, and at worst lead to baseless censorship.

Citizens should be wary, and pay close attention to the conversations being had by policymakers attempting to regulate speech. At OpenMedia, defending free expression is at the heart of what we do — and we won’t let controversy around this new buzzword become the latest excuse to censor the Web.

Join us, and stand up for free expression.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: Flickr/Thomas Hawk