“Everybody talks about the weather,” Mark Twain observed, “But nobody does anything about it.” A century and a half later, scientists are looking for a way to do something about the weather, and lawyers are studying who should pay for the work.

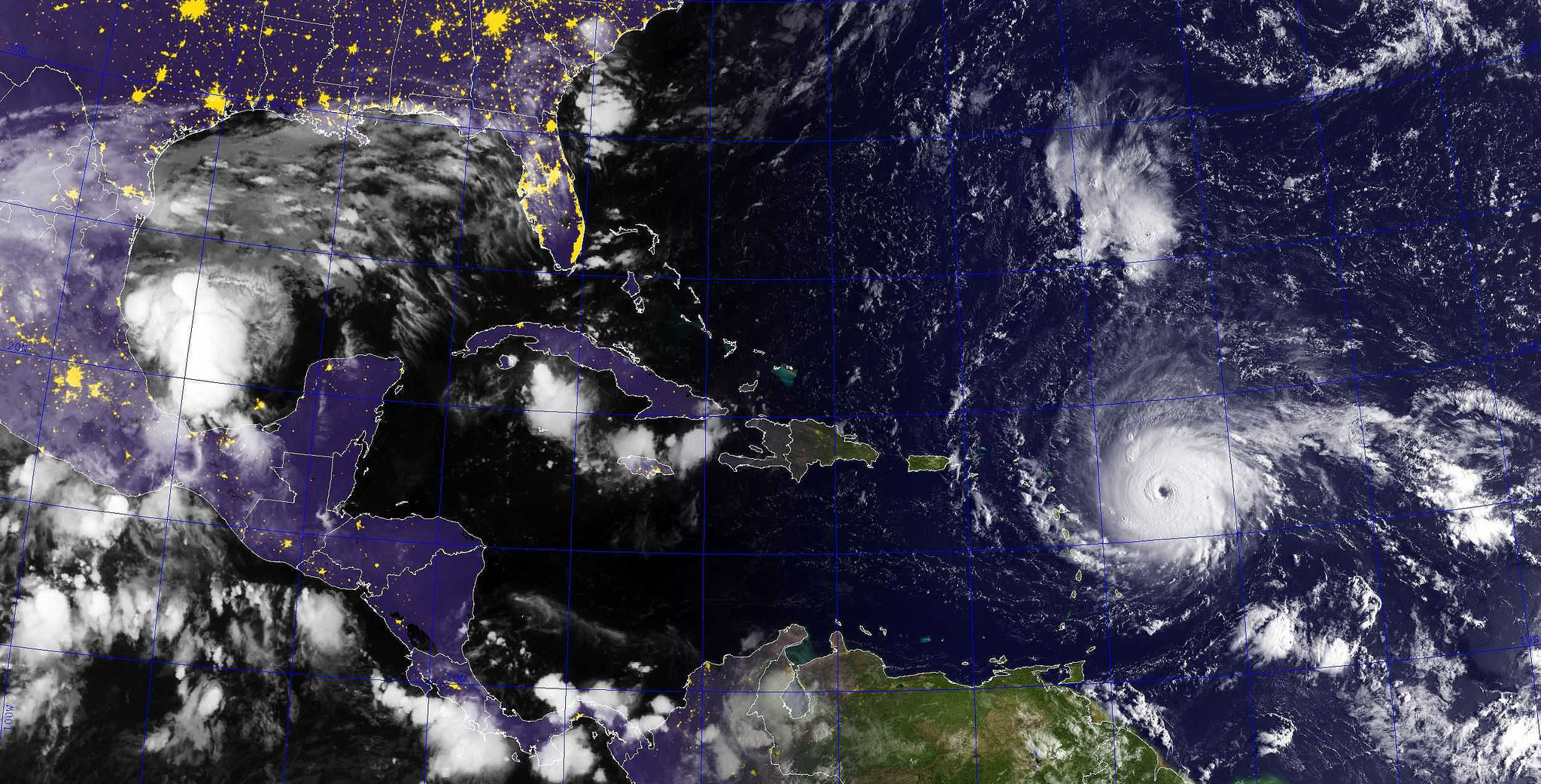

As the U.S. Gulf Coast reels under the impacts of Hurricanes Harvey, and probably soon Irma and Jose, disaster specialists, urban planners and insurance companies already estimate that cleaning up and repairing each region will cost tens of billions of dollars — $40 billion to repair Houston, perhaps as much as $125 billion for Florida, depending whether the 400-mile wide storm hits as a Category 4 or Category 5 hurricane.

Evidence is mounting that such cataclysmic storms are not unforeseen natural events or Acts of God; they are the foreseeable (and foreseen) result of human impact on the climate. The International Panel on Climate Change predicted extreme weather years ago. The problem until now has been to identify who is responsible for the damaging greenhouse gas emissions.

In 2014, climate researcher Richard Heede narrowed down emission sources in his paper, “Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010,” published in the influential journal, Climatic Change.

Heede wrote: “This paper provides an original quantitative analysis of historic emissions by tracing sources of industrial CO2 and methane to the 90 largest corporate investor-owned and state-owned producers of fossil fuels and cement from as early as 1854 to 2010.

“The purpose of this analysis is to understand those historic emissions as a factual matter, to invite consideration of their possible relevance to public policy, and to lay the possible groundwork for apportioning responsibility for climate change to the entities that provided the hydrocarbon products to the global economy…”

Heede suggested that while nations bear some responsibility for carbon emissions, so do the companies that profited from pushing the emitting products. He asks us to consider that “some degree of responsibility for both cause and remedy for climate change rests with those entities that have extracted, refined, and marketed the preponderance of the historic carbon fuels.”

This month, September 2017, Brenda Ekwurzel et al published a follow-up paper titled “The rise in global atmospheric CO2, surface temperature, and sea level from emissions traced to major carbon producers,” also in Climatic Change. Ekwurzel is a senior climate scientist and the director of climate science at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). The new paper adds quantities to the names of companies identified as chief emissions contributors.

Who bears responsibility for climate change has always been a key question in multi-national discussions. The 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change starts from the principle that nations that had produced the larger share of historical emissions bore a greater responsibility for avoiding “dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate.”

While most researchers traced emission source by nation or region, Richard Heede and then Brenda Ekurzwel decided instead to trace the commercial origin of the fuel that became the emissions. Heede pointed out that, for example, Nigeria exports a lot of fossil fuels but their value is not reflected in the national budget. However, their value is reflected in the profits of the company that bought the right to exploit the resource.

Ekwurzel’s group set out to see who profited. “This study lays the groundwork for tracing emissions sourced from industrial carbon producers to specific climate impacts and furthers scientific and policy consideration of their historical responsibilities for climate change…”

Their research identified 20 top companies that were responsible for 27 per cent of the increase in carbon emissions from 1880-2010 and nearly 20 per cent (19.6) of carbon emissions from 1980-2010 — including several state-owned oil companies. “Strikingly,” the researchers note, “more than half of all emissions traced to carbon producers over the 1880-2010 period were produced since 1986, the period in which the climate risks of fossil fuel combustion were well established.”

They conclude with a call for more research and the hope that, “These factors coupled with ethical, legal, and historical considerations may further inform discussions about carbon producer responsibilities to contribute to limiting climate change through investment in mitigation, support for adaptation, and compensation for climate damages.”

Two of the study’s co-authors, Peter Frumhoff and Myles Allen, published a piece in The Guardian on September 7, titled,“Big Oil must pay for climate change. Now we can calculate how much.“ They note that, “Lawsuits filed in July by three coastal California communities against ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP and other large fossil fuel companies argue that the companies, not taxpayers and residents, should bear the cost of damages from rising seas…”

Of course, there’s a big step between assigning blame and collecting compensation. Oil and cement companies can say that they were just playing by the rules. At the moment, it’s hard to see who has legal standing to sue for compensation, and what statute or international treaty they would use.

On the other hand, the world has already reached consensus that climate change is anthropogenic, human-caused according to work by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the World Bank, the 2015 Paris COP21 agreement, and the new Global Pact for the Climate (a kind of an environmental Bill of Rights launched last June at a conference hosted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature).

The Global Pact for the Climate actually begins by setting out personal and government responsibilities. The official first draft, presented by French President Emmanuel Macron, at the conference begins with these declarations:

Article 1

Right to an ecologically sound environment

Every person has the right to live in an ecologically sound environment adequate for their health, well-being, dignity, culture and fulfilment.

Article 2

Duty to take care of the environment

Every State or international institution, every person, natural or legal, public or private, has the duty to take care of the environment. To this end, everyone contributes at their own level to the conservation, protection and restoration of the integrity of the Earth’s ecosystem.

Not resting on their June achievement, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) will hold a free public one-day conference about the Global Pact in New York City on September 20, to present the draft Pact and gather public opinions. IUCN members include 218 State and government agencies, and more than 1100 non-government organizations. They will be pushing the Global Pact in their own regions.

Now the race is on to identify the companies that profited from selling fossil fuels, quantify how much carbon their products have added to the atmosphere, and build winnable lawsuits. Time is an issue, not only because the world is suffering from extreme weather, but because the oil companies are suffering too.

One leading oil company identified as a major polluter is Exxon. Exxon’s profits fell to $7.8 billion dollars in 2016, half of what they were in 2015. But Exxon still distributed $12 billion in dividends to shareholders — money that could make a big difference on ruined islands like Barbuda and St Martin’s.

With the Global Pact gathering momentum, it looks like maybe soon everybody will be talking about the weather — in court — as a way to do something about it.