“We’ll have to work … the dark side, if you will. We’ve got to spend time in the shadows … A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion … it’s going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal basically, to achieve our objectives.”

These were the words of former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney, during a Meet the Press interview with Tim Russert five days after the September 11 attacks of 2001.

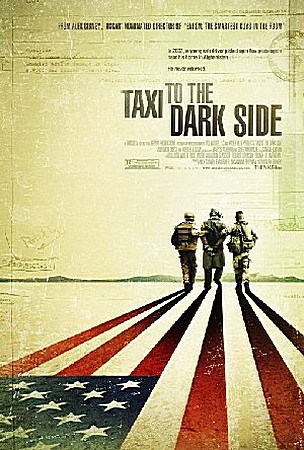

Acknowledging Cheney’s words as a telling precursor to America’s self-serving and calamitous ‘War on Terror,’ Alex Gibney’s 2007 documentary Taxi to the Dark Side provides viewers with a glimpse of what the ‘dark side’ of the Bush administration’s tactics and policies entailed for detainees who had been apprehended by U.S. military forces.

Film still relevant despite regime ‘change’ in D.C.

News articles published in the wake of Obama’s visit to Ottawa on February 19 suggested that many Canadians welcomed him with the same sense of blind optimism that Americans and much of the world has expressed. Recent polls indicate that Canadians foresee positive results with the Obama administration on several issues with respect to Canada-U.S. relations. However, why Canadians feel this way — whether it is because they have actually looked into Obama’s policies or because Obama is someone other than George W. Bush — is not as clear.

Taxi to the Dark Side received an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature but the film grossed very low numbers due to an alleged shortcoming on the part of ThinkFilm to distribute and market the film appropriately. Gibney’s frustration over this matter led him to file for arbitration in 2008, but the lack of viewership may also be due in part to a wilful resistance on the part of the public itself. Indeed, although the film is still in the New Releases section of many movie rental stores, the story it tells remains on the shelf in the same way that the film’s topics do — untouched or purposefully ignored.

Produced during the Bush Era, the film exposes horrors that many hope will no longer be applicable to the present. Obama is here, Bush is gone and yet the question of what to do with Omar Khadr, a Canadian child solider who has been in Guantanamo Bay since 2002, remains unanswered. In fact, Prime Minister Harper did not even bring this issue up during his recent meeting with Obama and many Canadians seem satisfied with Obama’s brushing off of the issue with yet another open-ended promise — ‘we are looking into it.’

The reaction, or lack thereof, to Taxi to the Dark Side in Canada is very similar to the reception of Khadr’s case by his fellow citizens. Khadr is part of a past that many would rather forget and that the future will hopefully take care of, eventually. Nevertheless, Taxi to the Dark Side is still relevant for any Canadian who is interested in more than just a surface level assessment of America’s policies under the Bush administration and for anyone who is interested in delving deeper into the policies of the Obama administration.

In a February 22, 2009 Globe and Mail article, conservative pundit Norman Spector makes an important observation, one which liberals and leftists may find more difficult to face squarely:

“Few Canadians have clued in yet to the policy similarities between Mr. Harper and Mr. Obama on issues such as climate change, extraordinary rendition and Afghanistan. Our British cousins, on the other hand, have already noted that Mr. Obama is refusing to recognize prisoners’ rights at Bagram — Afghanistan’s equivalent of Guantanamo. Nor did it escape notice that Mr. Obama’s Pentagon produced a report last week that found Guantanamo to be in compliance with the Geneva Conventions.”

Gibney’s film, which won an Oscar for best documentary, examines the case of a falsely accused Afghan taxi driver named Dilawar who was tortured to death by his interrogators at Bagram Airbase in 2002.

While the U.S. military initially claimed that Dilawar had died of natural causes, later reports revealed that the innocent man, a 120 pound, 22 year old son of a peanut farmer from a rural village in Khost Province, had been subjected to various forms of torture that included sleep deprivation, forced standing, forced nudity and sexual humiliation, as well as several beatings to his legs that resulted in them being “pulpified” (turned to mush). Only after their attempted cover-up had been exposed through investigative journalism did the military admit that Dilawar had indeed been the victim of homicide.

Shining light on cruel, counter-productive tactics

While probing America’s policies on torture and interrogation and the Bush administration’s endorsement and defence of these methods, Gibney also analyzes the results of these tactics in terms of what (if any) reliable intelligence can result from torture, as well as the long-term effect this approach will have on the populations of the countries that America has come to occupy.

Moazzam Begg, a British Muslim who was taken to both Bagram and Guantanamo Bay and later released without charge because he had always been innocent, remembers hearing Dilawar’s agonizing screams of distress while they were both detained at Bagram. Begg later recounts one guard telling him that if the detainees “weren’t terrorists before they came in … they certainly will be when they leave.”

The irony of America’s ‘War on Terror’ actually producing terror, both by inspiring violent methods of resistance in the countries they have invaded, as well as by physically imposing it on elements of the population through warfare and in certain isolated detention centres, resonates throughout the film.

For the more informed viewer, the images of the gagged and bound detainees with their arms shackled high above their heads will summon memories that will fuel foreboding. In 1981, after vowing to crack down on terrorism, Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak incarcerated and brutally tortured hundreds of men — some of whom later fled and joined Al Qaeda. One of these men, a physician from Cairo, went on to become bin Laden’s deputy. The lesson of history is that torture begets terror, rather than preventing it.

It is also important to note that the torture victims’ handlers appear at the forefront of the film as the main interviewees. Gibney lets their testimony expose the administration’s massive violations of the Geneva Conventions along with their calculated moves to protect those who issued the commanding orders from being charged with war crimes.

Gibney also shines a critical light on the motivation and meaning behind the sentencing of the soldiers who contributed to Dilawar’s death. While the soldiers were indeed responsible for their actions and should be held accountable, Gibney invites his viewers to consider the ramifications of the Bush administration’s directing of blame and responsibility away from the high ranking officials who sanctioned these actions, to the ground forces that carried them out.

Criticizing the means, not the ends (of the U.S. Empire)

Despite the fact that Gibney’s film has been accused by some on the Right of contributing to the lowering of the morale of U.S. military men and women, Taxi to the Dark Side can hardly be considered a critique of the American Empire. While Gibney must be applauded for his attempt to give a human face to the victims of America’s infamous off-shore detention centres, his analysis is still very much rooted in a jingoistic desire to, as he noted during his Oscar acceptance speech, “turn this country around, move away from the dark side and back to the light.”

Accordingly, no commentary is made about the fact that Dilawar’s interrogators admit little or no remorse while providing testimony about the disturbing course of events and their own complicity in Dilawar’s violent death. Rather, Gibney attempts to show that America was unwillingly hurtled into the “dark side” by the Bush Administration and is just as innocent as Dilawar’s interrogators, who stand by the excuse that they were merely following orders.

Blind spots

Gibney has dedicated his film to “…Dilawar, the young Afghan taxi driver, and my father, a navy interrogator who urged me to make this film because of his fury about what was being done to the rule of law.” Despite his supposed devotion to upholding the rule of law, he fails to provide commentary about America’s illegal invasion of Iraq or America’s transferring of detainees from countries like Iraq and Afghanistan to Guantanamo Bay, which occupies Cuban soil without permission.

While Gibney’s stated purpose was to focus on America’s use of torture after 9/11, context is key if he is committed to providing a balanced analysis of the whole story; his silence about whether America has the right to invade and occupy sovereign nations and then proceed to torture their citizens in the first place — some of whom are fighting the presence of their invaders, and others like Dilawar who were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time — is deafening. Moreover, Gibney says nothing about the indirect causes of Dilawar’s death, namely, the American invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, only talking about prevention by suggesting that the rules and regulations around American interrogation methods should be strengthened and better enforced.

That America has only recently fallen from Grace is impossible to accept if we dig even only a little deeper into the memory hole that has come to replace history before 9/11. As Naomi Klein notes in a 2005 article in The Nation: “The terrible irony of the anti-historicism of the torture debate is that in the name of eradicating future abuses, past crimes are being erased from the record. Since the U.S. has never had truth commissions, the memory of its complicity in far-away crimes has always been fragile. Now these memories are fading further, and the disappeared are disappearing again.”

Whose morale should we be worried about?

During a 2007 interview with Beckey Bright from the Wall Street Journal Gibney responds to claims that his film could demoralize America military members by stating that he hopes “…not to have an impact on morale. The military felt it had clear guidelines that were being fiddled with and undermined by civilian leadership. It’s up to officers to instill guidelines and it’s up to leadership to ensure guidelines are being followed.”

Throughout Bright’s interview Gibney reveals that Taxi to the Dark Side is more about what he identifies as an erosion in the sanctity of the American military than about the victims of America’s military. Gibney openly acknowledges this position later in the interview: “With this film, I try to get inside the thinking of the perspectives of those who were involved. I thought it would be more interesting to see this story from the inside out. The viewer is meant to see the story the way the soldiers did. Far from being a leftist screed, I think it’s quite the opposite.”

He goes on to show the extent of his empathy for the torturers: “These [soldiers investigated over Dilawar’s death] are regular guys. Not bad apples. The administration has referred to the abuses at Abu Ghraib as the work of a few bad apples. But like the movie’s title, most of us have a dark side, and we will go there under certain circumstances.”

By leaving out the indirect causes of Dilawar’s death, Gibney fails to adequately provide the perspective of the person that is central to his film’s arguments. The film received an Oscar, but with all its emphasis on blaming an administration that is no longer in power, Gibney’s documentary remains rooted in a very distinct period in the past that many would like to forget, even though its focus is still very relevant to the present. Accordingly, rather than producing a meaningful impact with his well-crafted analysis, Gibney’s film becomes yet another addition to the existing library of anti-Bush films.

In Canada, Gibney’s film remains unnoticed or blatantly ignored in the same way that Omar Khadr’s case is constantly brushed aside or buried beneath other issues. Unlike Khadr, who was only a minor when he was apprehended, Dilawar was a young Afghan man with a new family. One could also argue that Dilawar was in fact luckier than Khadr, for at least he was able to leave Bagram five days after his arrival.

Khadr, on the other hand, who is now 22 (he was 15 when he was captured), was transferred from Bagram to Guantanamo and has been tortured on several occasions. Unlike Dilawar, Khadr’s death has been impeded, no matter how much he may have wished for it; his inability to know the length of his imprisonment is yet another kind of torture that he continues to be subjected to with the help of the Canadian government’s willful indifference. Dilawar’s death was tragic, but Khadr’s life must be unbearable. He was apprehended as a child soldier and remains in Guantanamo Bay untried, seven years after his arrival.

The taxi driver may have been murdered, but America’s Dark Side is still alive and well.

There will be a special screening of Taxi to the Dark Side Saturday, Mar. 28, 7p.m. at Vancouver’s Pacific Cinematheque, 1131 Howe St, presented in conjunction with the Canadian Muslim Union, Siraat and the Pacific Cinemathque.

Jasmin Ramsey is a Vancouver-based writer and photographer.