Since the publication of his book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the runaway bestseller that documents the Marx-like tendency for inequality of wealth to increase as capitalism marches onward, Thomas Piketty has become that rarest of things: a celebrity economist. You may be thinking, “OK, but what does that have to do with the First World War?”

The straightforward answer is that Piketty finds that the only things that can break the inexorable march to more inequality are catastrophes, system-wide shocks that destroy wealth and reduce the return on investment to the wealthy. Shocks such as First World War, the Bolshevik Revolution, the stock market crash of 1929, the ensuing Great Depression, and the Second World War. Overall, their effects dominate the whole period from 1914 to 1945.

This is the good news, if you will, the ray of hope from the darkest of times on the equality front.

That catastrophe has been necessary to lessen gross inequalities, to break the structure of inequality, reinforces the reputation of economics as the dismal science. It is certainly a stark counter to the Panglossian, mainstream expectation that the operation of the market would “naturally” progress toward increased equality.

Piketty examines the historical data for rich countries — some, but not all; Canada does not make the list — from the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the late eighteenth/early nineteenth centuries down to the present: Britain, France, United States, Germany, Japan. He properly infers that what is true for these countries must be true for rich countries in general.

Piketty’s message is summarized in the arithmetic truism that whenever r (the rate of return on capital or wealth) is greater than g (the rate of growth of income or output) wealth or capital accumulates faster than income grows and therefore, inequality widens. Conversely, whenever r is less than g, with the result that the share of income going to capital decreases, inequality lessens.

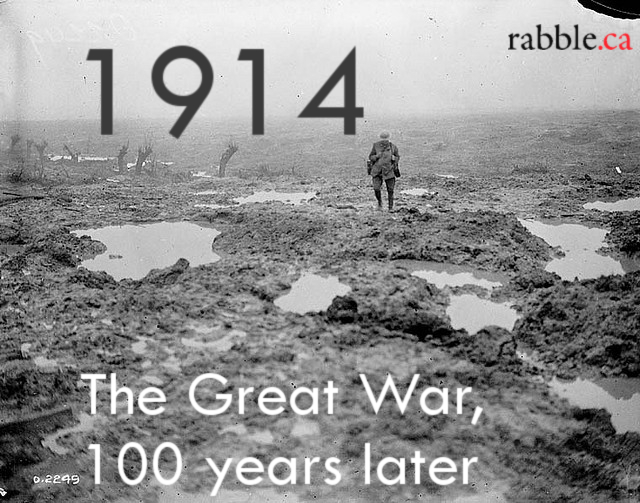

The catastrophe of the First World War destroyed capital or wealth, especially for people of large fortunes, and particularly in France. It takes time for the rich and powerful to restore the status quo, so inequality is decreased for some time.

We need also to look for what determines r and g, and, in the special cases highlighted by Piketty, in a way that reduced inequality. With the need to fund the war, countries resorted to progressive income taxes and inheritance taxes which lessened r, while the economic stimulus of war spending increased g. Both helped to put r below g.

As the war progressed, workers tended to increase their demands, a process that accelerated after the war. Recall the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919; when wages were pushed up by labour militancy, the return to labour increased relative to capital, thereby lessening r.

What Piketty has done is demonstrate how hard it is to redistribute wealth more equally. That is something political economists already knew. And honest economists too for that matter: the great Paul Samuelson said that if you took from the rich and gave it to the poor in the morning, the rich would have it back by the afternoon if you let them.

Piketty is telling us that things are even worse than most of us thought, with no easy answer at hand. No-one’s arguing that we start wars, or create other catastrophes. The lesson from Piketty is we have truly to try if we want to make a dent in inequality.

There is a ray of hope here. The 1% who are superrich and the 99% who are the rest of us has become part of the political discourse thanks to the Occupy Movement that was taking place as Piketty’s book was going to press. With the people and the professors united, anything is possible.