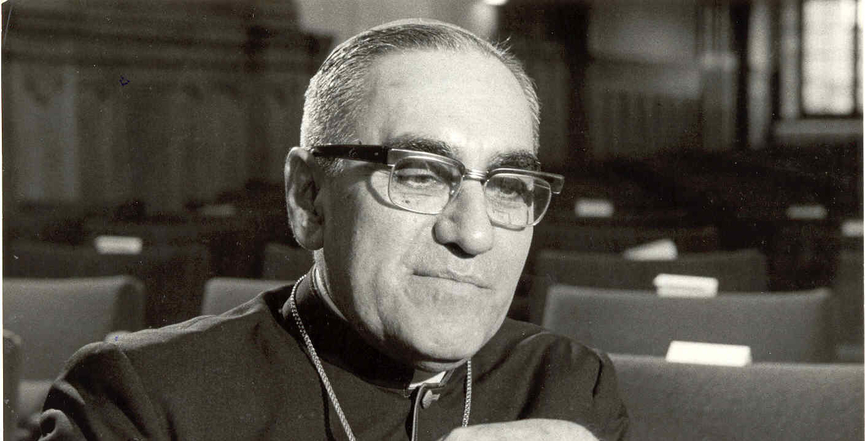

On March 30, 1980, I was one of at least half a million people who attended a funeral in San Salvador. It was the funeral of Oscar Romero. For those who may not know, Oscar Romero was the Archbishop of San Salvador from February 7, 1977 to March 24, 1980. He was assassinated on March 24, 1980, while presenting the eucharist at a mass for a deceased elderly community member.

Oscar Romero was murdered because of his unequivocal opposition to the violation of human rights in El Salvador, the government’s violent military repression and the country’s extreme poverty. On the day of his funeral, the Salvadoran army attacked the crowd gathered around San Salvador’s cathedral, killing several hundred people. This year marks the 40th anniversary of that horrendous assassination which I remember as if it was just yesterday.

Some would argue that Oscar Romero was chosen as archbishop because of his “conservative” views and because he sided with the powerful economic elite. After all, he did have good relations with members of the oligarchy at the time of his appointment. It is said that San Romero underwent a moment of transformation or conversion just weeks into his position as archbishop when a close Jesuit friend, Father Rutilio Grande, was assassinated by El Salvador’s national guard. Many believe the killing of Father Rutilio Grande and two of his assistants, 72-year-old Manuel Solorzano and 16-year-old Nelson Rutilio Lemus, was the catalyst for Romero’s “conversion.”

There are so many ways one can reflect on Oscar Romero’s life and legacy. We can talk about his theological courage, his struggle with the hierarchy of his own church, his determination to stand with the most vulnerable, and his impact on all people — not just Christians — around the world. The list is long.

Oscar Romero once said: “I have been frequently threatened with death. I must say that, as a Christian, I do not believe in death without resurrection: if they kill me, I will rise again in the Salvadoran people.”

As a Salvadorean, I have witnessed over these 40 years the “resurrection of San Romero,” not just in the Salvadorian people, but in people around the world. In Toronto, where I now live, there is a street in a housing co-op that bears his name. Toronto also has a refugee centre and a high school named after Romero. I am sure there are more “signs of Romero’s resurrection” across Canada.

In June 2019 I visited El Salvador. Everywhere I went there were photos and statues of this beloved man, as well as highways, schools and community centres named after him. Even El Salvador’s international airport is named after Oscar Romero. When the plane landed, and I saw his name in big letters at the airport, I thought: “yep, you rose again in the Salvadorian people.” I leave to your imagination the feelings and emotions I experienced when I landed in San Salvador. Writing this piece brings back those feelings and emotions.

I remember the soft, humble, down-to-earth man with a gentle smile who presided over my confirmation just months after being appointed Archbishop of San Salvador in 1977. It was in the unfinished basement of San Salvador’s cathedral, which was under renovation at the time. It was a small gathering and well in line with San Romero’s humility.

I close my eyes and try hard to go back to those moments. I want to remember what he told us, remember the sound of his voice. I can see his face, but I cannot for the life of me remember his words. It’s not because I wasn’t paying attention. He kept it short and simple. He was aware that actions speak louder than words. He knew that as inquisitive young people we were listening not only to him but, like him, we were also listening to the people and what was going on around us at the time.

He once said: “The spirit speaks to me through the people.”

He trusted that the spirit was speaking to us.

What I do remember are the hours, days, weeks, months and the social context leading to Romero’s assassination. For example, on January 22, 1980, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in San Salvador to demand better living conditions, respect for basic human rights, and an end to violent military repression. The government’s response: more repression and killings. Many died right in front of Oscar Romero’s cathedral. I know because I was there. January 22 is infamous for another terrible tragedy. In addition to the massacre in San Salvador, it is also the anniversary of the genocide 48 years earlier, in 1932, of more than 30,000 Indigenous people in the western part of El Salvador.

On January 31, 1980, in Guatemala City, a group of Indigenous people occupied the Spanish embassy. In response, the Guatemalan government security forces burned the embassy. Thirty-seven people, mostly Indigenous people died, including Vincente Menchú, father of Nobel Peace Prize recipient Rigoberta Menchú Tum. That, in a nutshell, was the social context in which Oscar Romero’s assassination took place. He joined thousands of human rights defenders who were assassinated. Sadly, 40 years later, Indigenous human rights, water and land defenders are still being persecuted and assassinated worldwide.

Since that day, more than 40 years ago, the month of March has been a loaded month for me. It’s full of so many memories and emotions. From deep sadness to anger, from longing to overwhelming frustration. The feelings and emotions are mixed and contradictory. I am happy the Vatican finally recognized what we, Oscar Romero’s people, have always known: that Oscar Romero was, is, and will always be a saint. However, I am frustrated and profoundly disappointed that, four decades since his martyrdom, poverty, inequality, corruption and violence are still too big a part of life in El Salvador.

Every year on March 24 I celebrate the life of this exceptionally and genuinely generous human being. Only someone with the sensitivity and love of Oscar Romero can live and give his life for his people. Only someone with such a deep connection to and understanding of Jesus can feel and say:

But perhaps my favourite Oscar Romero teaching, the one I always keep in mind as I go through my own life, is this one:

Alfredo Barahona is the KAIROS blanket exercise global and newcomer coordinator with KAIROS Canada

Image: Felton Davis/Flickr

Editor’s note, March 30, 2020: A previous version of this article incorrectly suggested that in Guatemala City a group of Indigenous people occupied the Spanish embassy, which was then burned by Guatemalan government forces, the day after Oscar Romero’s funeral. In fact, the embassy occupation took place on January 31, 1980, nearly two months before Romero’s assassination on March 24, 1980. The article has been corrected.