It’s the final week of our supporter drive and we need you, gentle reader! Please help rabble.ca stop Harper’s election fraud plan. Become a monthly supporter.

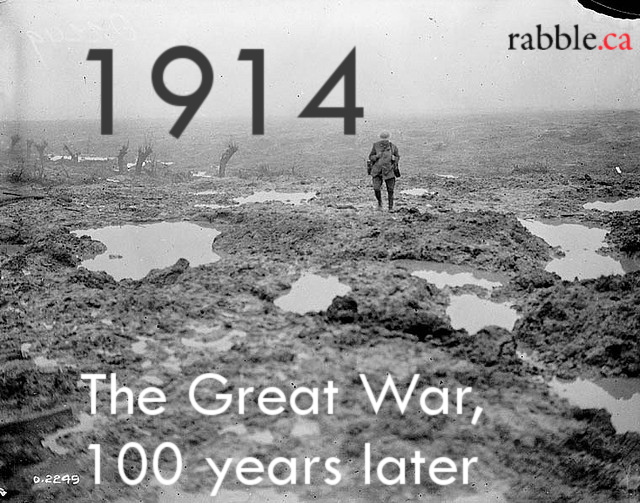

Watching World Cup soccer on TV and reading about the First World War on the occasion of its centenary, keeps this ancient blogger on his learning curve.

A classic book on the First World War (a.k.a. the Great War) and Britain is Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory. Writing about football (as soccer is known in Britain) Fussell observes “[T]he young man’s fondness of it was held to be a distinct sign of his natural superiority over his German counterpart” with an alleged herd-like quality. It makes men “individuals” and “daredevils” with a clear sense of “playing the game.”

Seeing war as a game, and a game that is popular and liked, makes men see war as an innocence that it most definitely is not. The name of the war game for the First World War ought to be dead men walking. For the “individual,” the odds are to be killed if you keep playing the game.

In Fussell’s words, “One way of showing the sporting spirit was to kick a football toward the enemy line while attacking.” Done in 1914, only months into the War, it “soon achieved the status of a conventional act of bravado.” In the first and most famous example, in preparation for an attack, a company commander with four platoons got one football for each and offered a prize to the one which first kicked its ball, with the men of the platoon in hot pursuit, up to the German front. The men were persuaded this was a “walkover.” The commanding officer kicked off the first ball and was killed instantly by German machine guns, which was predictable. But he got his reward: “Two of the footballs are preserved today in English museums” and his name is in the history books.

No wonder the Brits feel badly when their team is beaten, “bloodied,” in the first round of the World Cup. As for the Germans, they live on.

Still, there’s a good side to soccer and the War. In sudden uncoordinated outbreaks of deep decency by the men themselves, in Christmas 1914, British and German soldiers went into the deadly No Man’s Land between their two trenches, declaring a de facto ceasefire, and danced and sang and played soccer.

It was one the most inspiring and deeply democratic moments of the War and has been much celebrated, the subject of writing and plays. Left to themselves, the men in the trenches craved peace and fraternity and saw soccer as part of that package. Their high command roundly condemned what was done and it never happened again in anything like the same scale.

Let us note parenthetically that in Brazil professional players, insisting on players’ rights vis-a-vis their clubs and fans, have begun “locking arms at the start of games and refusing for several minutes to kick the ball. ” (New Yorker Jan.13, 2014) Was there any mention of that in the hours of coverage of a World Cup taking place in Brazil?

On TV, on the big screens, it is painfully obvious both that soccer is a cruel sport, like hockey, that brings out the aggressive side of the players and increases the hurt they do to themselves, and that, unlike hockey, the culture has built into it, as the norm, faking injuries. As The New Yorker points out, in the world outside soccer this kind of behaviour is called “malingering,” that not only sets a bad example for all of us, but in the armed forces, as a serial practice, is a serious and punishable offence. In the Great War, a soldier charged with “malingering” risked being executed.

American soccer players, to their credit, though part of the most individualistic of cultures, deplore these theatrics, and made it out of the first round of the World Cup.

And then there’s the literal connection of soccer and war: the so-called Soccer War, between El Salvador and Honduras in 1970.

With tensions running high between the two countries over immigration and land reform, soccer between their teams competing for qualification for the FIFA World Cup set off riots between the fans which became the tipping point for war.

It’s not news, but the fans can be the problem, but that “unsportsman-like acitivty” is part of the “game.”

I’m back, watching the TV at home — where no-one riots — and reading the books. But with a better understanding that war is not a game and a game is not war. We can’t change the Great War but we can our memory of it. We can urge that soccer be thought of as simply a game, a beautiful, thrilling game of co-operation and co-ordination, that needs to be played without deliberate bodily harm to others and without fakery. Non-violence is contagious. And with our increased awareness of the long-run consequences of concussions, shouldn’t something be done about the risk from headers?