Excerpt from Ten Thousand Roses: The Making of a Feminist Revolution

For the people hear us singing Bread and roses, bread and roses

— “Bread and roses,” Feminist anthem by James Oppenheim

By 1977, feminists were everywhere: on campus, in the unions, in the professions. Services like rape crisis centres, women’s centres and daycare centres had begun to spread beyond the big cities. A movement against violence against women was beginning to cohere. But much of this was invisible to the general public. The media, for the first of many times, was proclaiming that women’s liberation was dead. And ideological differences within the movement became ever more present as socialist feminists, liberal feminists and radical feminists staked their claims to the various issues. In this milieu, a group of women in Toronto decided to organize the first International Women’s Day celebration in English Canada.

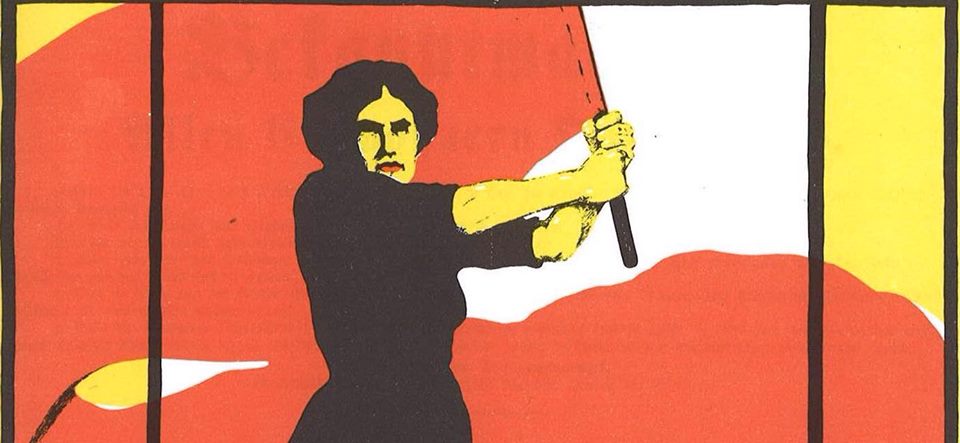

International Women’s Day had been celebrated across Europe and in Communist countries since the early twentieth century. The date of March 8 was fixed in 1977 by the United Nations. Its origins lay in the struggle of working-class women for bread and roses, a living wage and a better life. There are many myths about the specifics, including that it commemorates the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City on March 25, 1911, in which 140 immigrant women lost their lives because the bosses had lock them in, and the strike of Russian women for peace and bread at the end of February 1917, which kicked off the Russian Revolution. Quebec women had begun to organize their own IWD celebrations in 1973.

The organizing for International Women’s Day in Toronto pulled together a cross-section of feminists active in women’s groups and in various progressive organizations. As a grassroots coalition open to everyone, it embodied, sometimes quite painfully, the diverse voices in the women’s movement and the changes these women were demanding. Depending on the time of year, organizing meetings were held monthly or weekly, with as many as a hundred women sitting in a circle discussing the issues.

IWD organizing continued in Toronto after that first year, and each annual demonstration was linked to a key issue. The event was quickly taken up right across the country, becoming a gathering point for feminist activists and their allies.

International Women’s Day Coalition

Carolyn Egan

In the fall of 1977, I was approached by Varda Burstyn, who was a member of the RMG, the Revolutionary Marxist Group. She was pulling together a meeting of women from a range of organizations to talk about the perception in the newspapers that the women’s movement was dead. We were concerned because, since 1975, the International Year of Women, there had been no broad manifestation of the women’s movement. During that meeting, we agreed to plan an action for March 8, 1978.

As the planning began, a very real political difference began to emerge. There were women who defined themselves as radical feminists and those of us who defined ourselves as socialist feminists, and no doubt many in between. To my mind, the question was about how to organize, how to be inclusive and build a broad mass movement, but it became focused on whether or not men should be allowed to participate in the march.

The debate became quite sharp, to the point that we had to organize some decision-making meetings. On our side, the argument was that we wanted the march to be broad and have trade unionists come out and women from the immigrant communities, and a lot of them worked side by side with men. There were two or three meetings debating this, with about 80 women at each meeting. When the final vote came, our position won three to one. Some of the women who took the other position felt they could no longer work with us. We were saddened by their withdrawal, but we decided we had to go on.

It was a big gamble, because we didn’t know if we would be able to have an impact on the broader community. We had booked Convocation Hall at the University of Toronto. We had called it for 11 a.m., and at five minutes to eleven the hall was empty except for the organizers. My heart was sinking. And then someone who was outside came running in and said, “They’re coming, they’re coming,” and within fifteen minutes the hall had filled right up. It was mainly women who came, but there were some men as well. It was a dramatic moment. The women’s movement had really not been in the streets up until then. There was a march in ’75 for the International Year of Women, but otherwise nothing. For the organizers in 1978, the turnout was a confirmation that the politic we were arguing really had impact. The march we went on through the streets of Toronto was a powerful thing, and it was picked up in the press.

The night before the march, the women who had left the group held a women-only event. It was maybe two hundred women and a small march. But the difference was dramatic. That night you had the women who func- tioned within the structure of the women’s movement, but the next day you had a broad cross-section of women who believed they were struggling for women’s equality.

Susan Cole

Lesbians were trying to get recognized inside feminism. Lesbianism was considered a liability. We were at the IWD meetings and sniffing these things out. We were coming at it from the point of view that this was a woman’s event. All women should be welcome, and guys should stand to the side. The Trotskyist strategy was not to limit it in any way. The lesbian point of view went against that. In those days we were loud, and we knew that we weren’t dealing with popular opinions. But I still feel that a women-only expression was a reasonable thing to bring up. A woman’s

1. The Trotskyists referred to here are the Revolutionary Marxist Group (RMG) and the League for Socialist Action. The RMG emerged from the break up of the New Left and was led by a breakaway group in the left wing of the Waffle. It formed in 1973 and disbanded in 1977. The League for Socialist Action was an older group that had been active in the abortion movement.

A dance was okay; the other side thought that was a compromise. But we wanted the demo for women only. It wasn’t about having sex, it was a movement for social change, and we felt trivialized. We felt that there would be nothing more powerful for women to see than a large group of angry women asserting themselves. Politically speaking, we felt that even though the numbers might be smaller, the impact would be stronger. We were trying to articulate a different aesthetic.

This was the first time lesbians were demanding to be heard. Some of us were also members of WAVAW, Women against Violence against Women, and we were fighting for violence against women to be heard in the women’s movement as well. Socialist feminists had been political longer, and their politics came from a different place. The movement against violence against women came from women who had had that experience. That dynamic is particularly Canadian. In the U.S., violence against women was part of the women’s movement from the beginning. In Canada, the most sophisticated political people were socialist, which was different. The radical feminist view was that everything springs from gender difference. That was the politics I was working on.

These were hard things to talk about, and it was easy to dismiss us because of the lesbian issue. The Trots had a single-issue approach. They weren’t interested in multiple issues. They saw lesbianism as bad for feminist organizing, especially at that time. Lesbian organizers were closeted because they were afraid of repercussions. People wanted a political movement that would draw people in, and homophobic straight women were afraid that the lesbians would turn people off. In some ways, we were the backbone of the movement, and yet we were invisible.

IWD was fundamentally democratic, meeting every month all through the year. It was a place to find out what was going on. I wanted to be part of it. The debate was intense, and then there was a vote. I remember the WAVAW women standing at the back of the room with our arms crossed. We walked out of the meeting when we lost. This was a time of confrontation politics, and we wanted to do something different.

We organized our own fair that year and got a permit and marched through the streets. It had a different feel. It was more of a celebration, but it was still political. Later we decided we would go back to working on the big demonstration, but it took a while. And then things started to heat up around the sex and pornography stuff. IWD was the first stage in the rumbling. I think the pornography debates took it further.

Varda Burstyn

The way it started in Toronto was that I had been a member of the Revolution Marxist Group, RMG, for six years. We were a small group and we were discussing joining with the Trotskyists. Outside, tremendous things were happening. The women’s liberation movement started in the late 1960s, and in Toronto there was a tremendous crisis of political direction. Broadside, a monthly newspaper that was the voice of radical feminists who thought everything flowed from men and that they were the enemy, was forming in Toronto. They were launching their WAVAW and did important work. We’d had ten years of social democratic and trade union discussions of feminism. But they didn’t have anything to pull them together or any way to place themselves in the political landscape. There were liberal feminists as well who felt the pie was fine but that they wanted a more of it. This concerned me because the radical feminists couldn’t provide the full leadership that was necessary. Here we had a huge wave of women radicalizing, and I thought we needed an event to cohere that. It seemed to me for a variety of reasons that a big event that would allow us to pull everyone together would be to occupy a space at Convocation Hall at the University of Toronto to see ourselves and speak to ourselves and take us out there into the world.

We identified ten women who we felt were particularly important in the women’s movement. We included the WAVAW women and we called a meeting. We had a series of meetings, and WAVAW and IWD meetings were going in tandem. So when we had the division with WAVAW, I thought it was a failure. On the other hand, if you say that you want to be inclusionary, then you can’t exclude men, it doesn’t make sense.

The reason it worked is a lot of the women who were part of that original organizing committee also wanted to have some way to act. They didn’t want to go to the NDP, which wasn’t feminist enough or socialist enough. They wanted to have a way to show themselves and there was a great will to work together. So we were able to achieve balance within that. There were struggles and negotiations among those of us who remained because there were a variety of feminists. There was a tremendous will to come together.

We organized from the very first meeting for every woman there to identify individuals and organizations that each woman would bring to the next meeting. We chose people on the basis of their track record to organize; people who were embedded in their milieu. To join our first group, you had to commit to doing that. It was an unbelievable six months of organizing. Everybody went to the people they were involved with and brought them and their organizations. We formulated motions to support it. Union locals passed resolutions and their people came and carried banners; women in international solidarity groups did the same thing. We wanted to show both organizational and individual support. It was important to all of us to show that feminism was socialist feminism. It was part of a movement for socialism. It was important to show us as an important current of women, that we were connected to something big and substantial, so it was important to us to have endorsements. By the time we got to the rally, a hundred organizations endorsed us.

One doesn’t like to remember the mistakes one made, but I doubt we were against a theme of violence against women. We wanted to have a theme, and the majority of women didn’t want violence against women to be the theme. That was WAVAW’s theme, and we didn’t want that to be the theme of our first major splash. We were thinking it was important to have a front that the press could relate to and that would have an impact. We listed twenty demands and we had a debate about which would be the one to focus on.

Dionne Brand

I belonged to a group called the Committee against the Deportation of Immigrant Women (CADIW), which had a lot of links with WAVAW. We thought that feminists needed to organize around this issue, which was mainly the deportation of Jamaican domestic workers. We were disillusioned with the black community organizations. So we leafleted and organized meetings. There were just three of us who comprised the organization in 1978, but, remember, only five guys started the Black Panther Party.

CADIW went to the IWD meetings to raise the issue of women being deported. We felt there would be support for our demands there. Since we were still organizing in the black community, our relationship with IWD at that time was a nervous one. We didn’t know what the interests of those women were, nor did we see them as dovetailing with ours. So we went there in coalition mode, rather than to become part of the organization.

I went to Granada in ’83, and when I came back there was the beginning of the Black Women’s Collective. We started to get involved in IWD to bring that element to it. We still worked in the black community wanted to embody the women’s movement, to be part of it in a formal way that would also change it. We thought it should have a wider sense. In 1986, when IWD came up with the slogan “Women against Racism from Toronto to South Africa,” we decided we would pick up on that. We heard that it was going to be a year about anti-racism, and we went to the meetings. We thought this was our issue and we could give some kind of direction.

We came into the room and said, “Wait a second. What do you mean, and how do you do this, and what kind of decisions are you making?” There were capable women who had run IWD for a long time, and the bureaucracy of it was well in hand. So we came in conflict with some of the ways they did things. Suddenly it was very charged. We also had connections with some Aboriginal women and the Native Women’s group. We got in touch with them and invited them to join the meetings with IWD as well. At those meetings, when people started to vote on things like who should speak, what route the march would take, what the poster would look like, the writing of demands, we said, “Hold it.” We held up the meeting and said we had to caucus on some things. It introduced into the coalition the possibility that how decisions got made wasn’t necessarily democratic. Racism in the society means something about how power is distributed. You can’t have the tyranny of the majority. That shook things up in the coalition that year.

We had discussions in our group about how to proceed in coalition with other people who might not have all interests intersecting with yours. We had a central issue about the liberation of women, but we had a different sense as black people about what knowledges people have in the world and who we were with in the world. From being involved in radical left politics, you learned about the exclusion of women in decision making. Then we came to the feminist movement and we dreamed about how to organize it. We talked about how to work it out, and we read a lot, too.

It was hot. The women’s movement is where all this kind of stuff happens. It’s very charged and angry, but it’s where it happens. People from outside can look at it and see it as fighting, but we’re fighting for some- thing. It will look like it’s in disarray, a mess, but that’s what struggle looks like. You’re fighting for ideas, you’re fighting all the prejudices. It looks messy, and at the time you feel like, who do they think they are? I do think that the vision of us, 10 Black women, walking into the room was scary for people, and that played to our paranoia. Like, what the hell do you mean, scary? That’s a racist concept about what Black people represent, which is totally not what we are. We are in the weakest position, so how could we be scary? I think we had allies, and I don’t think the women who were upset with us were against us. I also think there were women who admired us. It was ground we had to fight on and for. I don’t think anyone coming into the room was who they were before. It was a transformative time. Its effects were both good and bad. I think it spawned some radical changes, but also some not-so-good changes. Some white women threw their hands up in the air because they lost control and so felt they couldn’t do anything. They withdrew their goodwill.

I also think there were people who interpreted those interventions as nationalist moments. In years after I would hear things like, “Okay, these people must always lead the march”—like “Native women must always lead the march”—and “These people must always do that.” Why should that be a fast rule? Not all the radical politics got spread through. It clumped itself down into that kind of nationalism, as opposed to a process of thinking and rethinking what this might involve.

When we went into IWD, we said that the racism thing is not like an issue that you can do and then go away. It’s how some people live, and there needed to be radical change in thinking to figure that out. The general society was also going through this guilt thing. We hated the guilt. Guilt is petrifying. Guilt means you can do nothing. Guilt also means that you don’t see how your life will change. Lots of decisions were made on guilt. I thought what the coalition needed to do was some workshops for white women about racism. Not where the black women and women of colour come in and say what racism is, but white women sitting down with each other and talking about how it works. We suggested that, and it was a no no. I don’t understand why. We wanted them to talk about how racism works in all our lives. We all live in the same space, and racism affects white women. Not just as perpetrators of racism—it affects your life, too. Who you think you can be friends with, who you don’t. It would have been a good, thoughtful way of going about things to have workshops about it.

After ’86, there wasn’t any organizing in the women’s movement that wasn’t inclusive. People really tried for inclusion. I think there wasn’t another IWD where the speakers weren’t varied. As much as it was difficult and rancorous, as much as people didn’t speak to each other for years, for years, I don’t think another discussion came up without attention to inclusiveness. That was good. What was bad was that we thought we couldn’t speak to each other after the fight. Everyone learned from it, not just white women but also black women and other women of colour . If white women can see racism as structuring their lives too, and not always to their benefit, as limiting their lives, though not in the same way it does for women of colour, then that’s the moment in which they can embrace the experiences of women of colour. And that is the moment at which they can challenge some of those things. We had it right about what we feel, but not always about what to do. I always hope for that moment. It didn’t happen in 1986, but I am sure it happened between two people somewhere. It’s not impossible for you to figure out what I might be living.

Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.