All budgets are political in nature, but Ontario’s 2013 budget — tabled by a minority government with a new leader — stands out as a case in point: it is carefully designed to survive a non-confidence vote.

It extends a few olive branches to the opposition NDP. A promise to reduce auto insurance premiums by 15 per cent. Increases in spending on home care, youth unemployment and infrastructure in rural areas and the north. Restructuring the Employer Health Tax to claw back the small business reduction from large corporations.

It hugs the curvature of tax cuts and low public spending enough to counter opposition Conservative complaints.

It takes baby steps on several files, such as social assistance, poverty reduction, and movement toward a solution to Toronto’s gridlock woes.

And its tone is a kinder, gentler version of the last budget Dalton McGuinty tabled a year ago, which launched Ontario into a year of austerity battles with labour.

But, in substance, Budget 2013 doesn’t shift from the agenda its predecessor set in 2012: Ontario’s government is still waging austerity, it continues to drag its feet on poverty reduction, it tinkers at the margins of the Lankin-Sheikh social assistance review, and as for economic growth, it continues to rely on the good people of Ontario to drive GDP with whatever money’s left burning in their wallets.

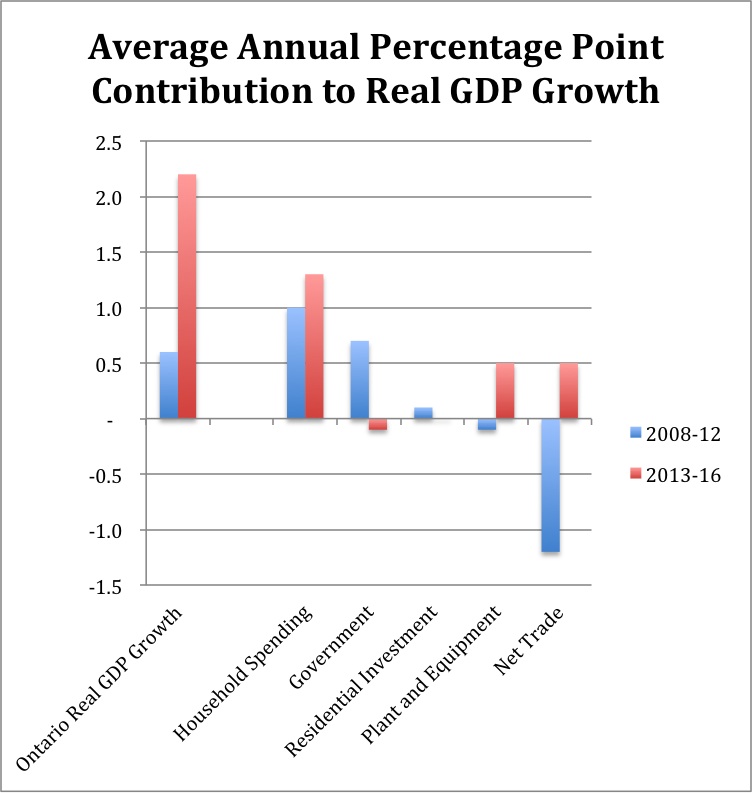

You don’t have to look beyond the government’s own charts to see the price of austerity. On page 181, the Budget presents the above chart, showing a breakdown of contributions to Ontario’s economic growth from various sectors of the economy, comparing the period between 2008 and 2012 and the period from 2013 to 2016.

The data for the 2008 to 2012 period underline the critical role that government stimulus spending played in averting an even worse recession. Government’s contribution was greater than overall economic growth. In other words, without government’s contribution Ontario’s economy would have actually shrunk in real terms over that five-year period.

However, the projection for 2013 to 2016 shows clearly how committed governments in Canada — including the Ontario government — are to austerity as an economic strategy. The projection is that after having led the recovery in 2008 to 2012, governments will actually detract from economic growth in 2013 to 2016. That is because, according to the governments; projections, between 2013 and 2016 their average annual contribution will be negative.

That means the foundation for this budget is four more years of austerity. While the government applies the brakes, Ontario is assuming that growth in business investment, consumer spending and a significant improvement in the trade balance will prevent the economy from sliding into another recession. This is precisely the recipe that created the double-dip recession in the United Kingdom and that has led to long-term stagnation in Europe. But while even the most enthusiastic boosters of austerity in the rest of the world are backing away, Ontario is forging ahead with its austerity strategy, sitting on the sidelines and hoping that consumer spending, business investment and a rebound in our trade balance will do the job for it.

Ironically, the government’s own numbers also show that the original case for austerity in Ontario was wildly overstated.

The following chart shows how Ontario’s estimates of the fiscal deficit gradually deflate from the forecast cycle through to the audited final numbers.

For example, it shows that for 2011-12, the deficit gradually declined from a 2-year forecast of $19.4 billion to a final audited number of $13 billion. For 2012-13, even before the final audited numbers are out (expected in September 2013), the deficit shrank from a 2-year forecast of $15.9 billion to the estimate of $9.8 billion in this budget. Based on this trend, we could reasonably expect the deficit for 2015-16 in this plan to be, at most, $4.8 billion.

Although time is proving just how overstated the Drummond report’s deficit projections were, the government continues to follow the report’s austerity prescription of no less than 362 places to cut spending. The budget claims the province is “moving forward with about half of the 362 recommendations” and promises to implement a total of 60 per cent of the recommendations.

In other words, Ontario remains in austerity mode, despite the mounting evidence that it’s doing more harm than good.

Teachers and school workers bore the brunt of austerity initiatives in 2012, as political casualties of the province’s austerity agenda. Their collective bargaining rights were revoked and their battle with the province made them the most visible face of austerity. Budget 2013 softens the tone of the assault on labour rights in this province, but fails to stand down from the austerity ledge.

Meanwhile, hidden dimensions of the price of austerity are beginning to poke through in Budget 2013. For starters, it is increasingly evident that the provincial government will not make good on its commitment to reduce child poverty by 25 per cent within a five-year period. Last year’s austerity budget put child poverty reduction efforts on ice, despite heartening evidence that earlier initiatives were actually making a difference for the province’s poor.

Budget 2013 commits the government to increase the Ontario Child Benefit (OCB) to $1,210 per eligible child in July 2013 and to $1,310 in July 2014. That’s behind the schedule the 25 in 5 Poverty Reduction Network was urging the government to adopt.

Despite growing calls to raise the minimum wage to $14 an hour in Ontario — to lift workers above the poverty line — there is no mention in the provincial budget of any scheduled minimum wage increase. The budget says the province will create an advisory panel of business, worker, and youth representatives — a move that will be viewed as a stalling tactic by those advocating for a raise after a two-year freeze.

There will be a one per cent increase in benefits to those who qualify for the Ontario Disability Support Plan (ODSP), three per cent (including a $14 a month top up) for those who qualify for Ontario Works (OW). But this increase fails to keep up with the rising cost of living — and those receiving OW and ODSP are among the most vulnerable in our province.

Meanwhile, the province is changing some restrictive Mike Harris era rules on OW and ODSP recipients (including asset limits) but the long shadow of Harris’ political attack on the poorest in the 1990s remains steadfast in Ontario. It’s a reminder about the lessons of austerity: groups who are scapegoated and services that are cut in the name of deficit reduction are never fully returned to their previous levels once government reaches its goal of balanced budget.

The following chart traces the real value of basic ODSP and OW benefits since 1993. Notably OW and ODSP benefits will be lower this fall, after the increases announced in the budget, than they were in 2003 when the McGuinty government took office.

When all is said and done, 16 out of 25 government ministries will be spending less than they were allocated last year. In fact, Budget 2013 trumpets that Ontario will spend less, per capita, on public programs than any other province in Canada.

The rest of program spending amounts, virtually, to maintenance. There will be a little more spending on home care — but not nearly enough to meet the growing demand of an aging population. Students clamouring for a break on tuitions won’t get one. No leadership on affordable, regulated child care.

There is some movement on Toronto’s public transit file: the province now appears ready to allow a toll lane to help the GTA get out of political and traffic gridlock. It is also ready to make permanent the two-cents-a-litre gas tax to municipalities. But those revenue tools are not nearly enough to save the day.

Finally, Budget 2013 fails to address the real cause of Ontario’s revenue problems: the unsustainable tax cut agenda that Mike Harris introduced in the late-1990s. The lost revenues from those tax cuts amount to $17 billion in forgone money the government could have been using to eliminate the deficit, trim down the debt, get young people, immigrants, and the long-term unemployed working again — having been sidelined for too long since the 2008 recession.

Despite all the mounting evidence that austerity in Ontario is doing more harm than good — our estimates is that austerity measures will act as a three per cent fiscal drag on the economy for several years — Budget 2013 failed to take the province into a new direction.

And for all of its claims of balance in its approach to the deficit, there isn’t a single major new revenue raising initiative in the budget. Ontario is relying entirely on cuts in services to Ontarians — a priority that means once the budget is balanced, the gap between the services we need and the services we are receiving will be even bigger than it is today, with our per-capita service levels stuck at the lowest among provincial governments in Canada.

Nice might have replaced nasty, but it’s still austerity.

Economist Hugh Mackenzie is a CCPA research associate. Trish Hennessy is director of the CCPA-Ontario.