Please help rabble.ca stop the ongoing corporatization of Canadian universities. Become a monthly supporter.

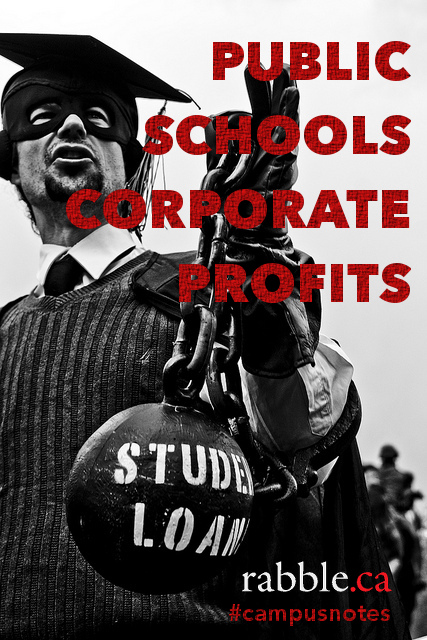

The firing of outspoken University of Saskatchewan Dean Robert Buckingham this May raised questions not only of academic freedom, but of the ongoing transformation of Canadian post-secondary institutions as sites of private profit rather than public education. rabble.ca is proud to launch this special summer series on the corporatization of Canadian universities, by USask Professors Sandy Ervin and Howard Woodhouse. See their previous entries here and here.

Canadian universities have become sites of knowledge production for multinational corporations to increase their global competitiveness and maximize stockholder value. Boards of Governors are increasingly composed of members of the corporate elite. Rather than oppose their economic and cultural domination, university presidents support it, taking up the rallying cry of “We must compete” as their mantra.

In what ways, then, do Boards of Governors (BOGs) and university Presidents enable the transformation of universities into private corporations?

BOGs are the highest level of authority in Canadian universities. They control the revenues and financial affairs of their respective universities. This includes the administration of all properties, the construction of buildings, and the determination of tuition fees. They also appoint the president and other senior administrators, and approve the appointment of faculty. As members of BOGs, presidents exert considerable influence over decision-making.

In the past 40 years, BOGs have been stacked with members of the corporate elite. As Canadian universities have been defunded by governments and have had to rely on alternative sources, captains of industry have used their alleged financial ability and multiple corporate directorships as leverage. BOGs at so-called elite universities like McGill, Toronto, and Queen’s have included directors from Teleglobe, TD Bank, Molson, Noranda, and Bombardier. BOGs at universities in different regions of Canada, like Calgary, Laval, and Dalhousie have included directors from RBC, Scotia Bank, TD Bank, Coca-Cola, and Bank of Canada. All universities are now drawn into the same net as decision-making power is vested in corporate representatives.

Members of the corporate elite on BOGs act as a powerful force normalizing market relations at universities. One example is the way in which the mechanistic discourse of corporate culture has replaced the language of education: Students become “educational consumers;” subject-based disciplines and the professors who teach them become “resource units;” curricula become “program packages;” graduates are now “products;” and “competing in the global economy” has replaced the search for knowledge and truth.

As evidence of this approach, Susan Milburn, chair of the BOG at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S), when she was vice-chair, compared the university to a “high-performing corporation.” On this view, the maximization of private money profits is no different from the advancement and dissemination of shared knowledge. This fallacious reasoning fails to recognize that the corporate market operates on a different, indeed opposing, logic from that of education. While the acquisition of money increases in value as it is accumulated by individuals or corporations, knowledge increases in value as it is shared, refined, criticized, and superseded by members of the educational community. This key difference does not compute.

People’s interests not represented

The current BOG here at the University of Saskatchewan demonstrates the typical corporate bias — it overwhelmingly reflects resource, property development, and financial sectors. You find no artists or cultural sector workers, farmers, unionized workers, officials from First Nations or multicultural organizations, or the large not-for-profit or nongovernment human delivery sector — all of which surely could be considered important stakeholders in both the Province and its University. It could be claimed that, otherwise, First Nations people are indirectly represented — the elected President of the Students’ Union, the Chancellor, and an official from a mining giant are proudly First Nations people. However, the latter two are deeply connected to the corporate sector — the Chancellor himself owns an oil company and the mining employee does not per se represent First Nations interests — but mining interests.

Seven of the ten positions then, other than the President as ex officio, reflect very strong corporate interests. Among the corporate representatives are BHP — Billington, the controversial global mining colossus that has been expanding its considerable reach into Saskatchewan’s highly lucrative potash industry. Several years ago BHP-B attempted a hostile takeover of PotashCorp of Saskatchewan, the world’s largest fertilizer and also major influencer of U of S policies.

The most significant board representation, and the most egregious in our opinion, has been that of Cameco Corporation, the world’s largest publically traded uranium company that seems unofficially to have a permanent seat on the Board of Governors. As a very abbreviated case example of what we consider to be a stunning conflict of interest and the power of corporate links, consider the following case: In the Fall of 2011 the BOG approved the establishment of the Canadian Centre for Nuclear innovation (CCNI) at the University of Saskatchewan. This was to be supported by a $30-million grant from the Provincial Government plus later additions of $5 million each from GE Hitachi (who recently shifted its Canadian Headquarters to Saskatoon, likely for the purpose of developing modular nuclear reactors in partnership with the U of S) and again from the provincial government.

The Chair of the BOG at the time was Nancy Hopkins, a director of Cameco with over $2,000,000 in Cameco stocks. Two of the University’s four vice-presidents had vested interests in uranium and nuclear development, and then President Peter MacKinnon had been the guest of Cameco in its northern operations that summer. CCNI clearly serves research functions for both the uranium and nuclear industries. (For more information on this convoluted set of networked relations see D’Arcy Hande’s “Follow the Yellowcake Road” and examine that article’s links). Finally, recall that according to Canada Revenue Agency’s recent suit, Cameco owes the Canadian and Saskatchewan taxpayers $850,000,000 in back taxes as was reported in the business section of The Globe Mail in May 2013.

U of T President: “We need a more market-driven system.”

University presidents play the same corporate game. Their salaries range anywhere from $275,000 to $1.2 million, and they also serve on corporate boards. While president of the University of Toronto, Robert Prichard was active on the boards of Imasco, Moore Corp., and Onex Corp. As president of UBC, David Strangway, was a member of the boards of BC Gas and MacMillan-Bloedel. And George Ivany, former president of the U of S, was rewarded with membership on the board of Cameco a few days after stepping down. He had been instrumental in persuading the federal government to bring the Canadian Light Source synchrotron to the U of S.

President Prichard even acclaimed the corporate market as the ruling principle of the Canadian university system: “We need a more market-driven, deregulated, competitive, and differentiated [i.e. product-mandated] system., production of better services to customers. The market model give (sic) universities more freedom…by allowing administrators to set fees higher and…by aggressively courting private donors.” The logic of the market is revealed in stark terms: universities must deregulate, and they mustcompete, bringing more products to market and providing better services to “customers.”

Ironically, the discipline of the market is seen as a source of freedom that allows administrators to raise fees and seek funding from the private sector. Once again the fact that higher tuition fees exclude large numbers of students does not compute. And the erosion of public university education by corporate “donations” does not even register.

In order to oppose these corporate linkages, we suggest the following measures:

-

Restrict the number of corporate representatives on BOGs to no more than one and prevent presidents from holding directorships on multinational corporations.

-

Broaden the membership on BOGs to include a cross section of the local population.

-

Ensure that academic decisions are made by faculty by strengthening established collegial procedures.

-

Ensure University Acts prevent presidents from having veto power over tenure or faculty appointments.

-

Strengthen democracy on BOGs by making meetings and minutes open and transparent.

-

Hold BOGs publicly accountable for all financial decisions.

Howard Woodhouse is Professor of Educational Foundations at the University of Saskatchewan and author of Selling Out: Academic Freedom and the Corporate Market (McGill-Queen’s University Press 2009; Alexander (“Sandy”) Ervin is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Saskatchewan and a long time board member of CCPA (Saskatchewan). His most recent book Cultural Transformations and Globalization: Theory, Development, and Social Change is in press with Paradigm (2015).