It’s now Halloween in Canada all year round. At every unexpected turn another grim apparition appears. The scream from one shock has barely faded when another ghastly spectre rises from the neo-conservative crypt of horrors to stalk the land, a headless, brainless zombie intent on political terrorism.

The faults of FIPPA

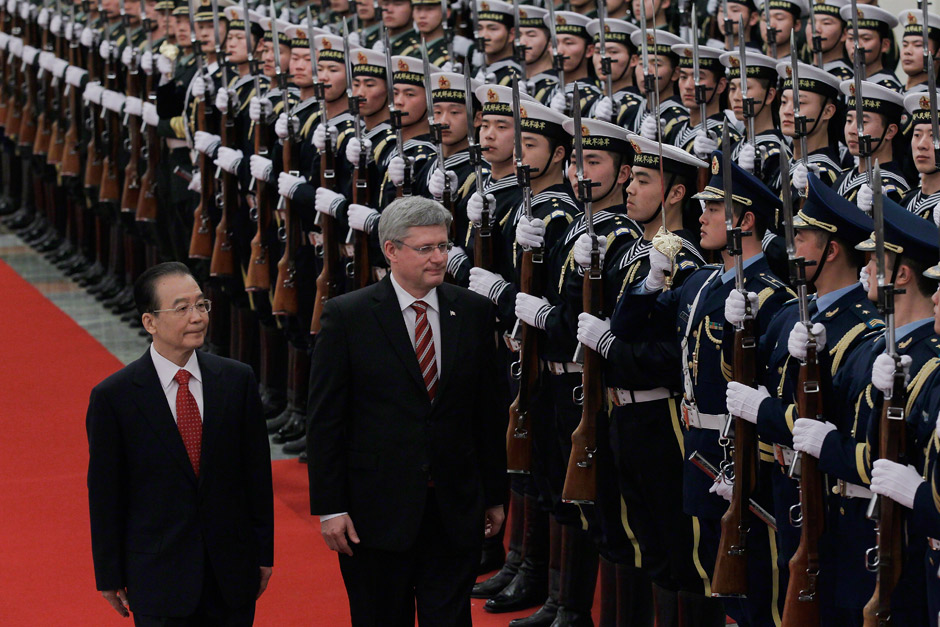

Today’s abomination is called the China-Canada Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPPA). This investment agreement, which many commentators feel is at least as important as NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement signed in 1993) in terms of its impact on Canadian trade, locks the country into a 31-year long pas de deux with a system that Andrew Nikiforuk calls “gangster capitalism.” FIPPA has suddenly leapt like a full-fledged baroque horror out of the Machiavellian political backrooms onto the front stage of Canadian politics.

Writing in the Ottawa Citizen, Terry Glavin calls this “protection agreement” a “protection racket” that works like this:

“Beijing promises that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will regularize its bribe system and put the boots to China’s subnational, provincial, county and municipal governments on behalf of Canadian companies, in the same way that the CCP’s enforcers put the boots to everyone on behalf of Beijing’s state-owned enterprises. So long as Canadian investors do as they’re told, everybody gets along.

“Beijing promises that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will regularize its bribe system and put the boots to China’s subnational, provincial, county and municipal governments on behalf of Canadian companies, in the same way that the CCP’s enforcers put the boots to everyone on behalf of Beijing’s state-owned enterprises. So long as Canadian investors do as they’re told, everybody gets along.

“To reciprocate, Ottawa promises that China’s state-owned companies will be similarly exempt from any impertinence from the Canadian courts, from the provinces and from municipalities. Any backchat — say, a law sensibly requiring that Alberta bitumen be upgraded and refined in Canada rather than pumped through Beijing-financed pipelines to awaiting tankers on the west coast — and the upstarts can be punished with penalties assigned by special, closed arbitration tribunals in decisions beyond the reach of judicial review.”

Although the NDP, Liberals, and Green Party are aghast at how this treaty is being railroaded through the House of Commons at breakneck speed, with virtually no parliamentary oversight, opportunity for examination by committees, expert analysis and testimony, or input from citizens, the real horror is a government that conducts itself in this way. In Stephen Harper and the triumph of the corporation state Frances Russell writes about the “open disdain for Canada’s system of Parliamentary democracy” displayed by Prime Minister Stephen Harper who has thrown the country’s democratic system “under the bus.”

“The Harper government has turned parliamentary democracy upside down. The government doesn’t answer to parliament, it requires Parliament to answer to the government. … This led the director of the Constitution Unit at University College, London, to write: ‘Canada’s Parliament is more dysfunctional than any of the other Westminster Parliaments. No prime minister in any Commonwealth country with a governor general, until Harper, has ever sought prorogation to avoid a vote of confidence.'”

Missing the boat or selling the store?

This chamber of horrors provides a fitting backdrop for another lesson from The nine habits of highly effective resource economies: Lessons for Canada, published by the Canadian International Council (CIC) and written by Madeline Drohan. The fifth habit selected by Drohan is what she calls “Get on the global boat and cast wide trade nets.” It provides a penetrating analysis of why trade is vital for Canada, and what kind of trade agreements are good — and bad — for the country. All trade agreements were not created equal and Canada can either be enriched and empowered, or sold down the river and swindled blind.

Canada has some natural advantages when it comes to trade. Our large reserves of natural resources, and our history of hewing wood and drawing water, place Canada 13th globally in goods exports (with a global market share of 2.5 per cent) and 18th in service exports (with a share of 1.8 per cent). This isn’t insubstantial, but it’s not stellar either given that the majority of Canadian exports (73 per cent) end up in just one market: the USA (in comparison, 34 per cent of American exports go to Canada).

However, our market share has been slipping badly over the past decade. The figure above illustrates the percentage change in export performance amongst the G-20 nations between 2000-2010. During that time Canada’s market share has declined 40 per cent, the second worst amongst the G-20 nations (trailing only that of the United Kingdom, whose share has slipped 44 per cent). This decline is at the expense of the BRIC nations; Brazil (+ 45 per cent), Russia (+ 55 per cent), India (+ 125 per cent), and China (+ 173 per cent); and Turkey (+76 per cent) and Australia (+ 42 per cent).

The CIC report notes that there are several factors responsible for this dramatic decline:

1. The inflated value of the Canadian dollar (a.k.a., Dutch Disease), an economic phenomenon that the Harper Conservatives continue to deny exists (see Dutch Disease denial: Inflation, politics and tar);

2. Declining Canadian productivity; and

3. Most importantly from the perspective of the report, that Canadian trade is concentrated in slow growing economies.

Indeed, 85 per cent of Canadian exports go to the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, France, Belgium, and Italy — all economies with average annual growth rates of under 2 per cent. Compare this with the BRIC nations: Brazil (3.5 per cent), Russia (5.5 per cent), India (7.5 per cent), and China (10.5 per cent). It would clearly benefit Canada to diversify its trade so as to be able to better connect to a wider variety of countries, and in particular, some of the economies where activity is currently strong. However, this is no panacea, and there are downsides (economic and social) in developing trade with nations where there is corruption, political repression, instability, or other problems. Canadian interests risk propping up un-popular or anti-democratic regimes.

However, as the CIC report makes clear, what is more important than whom Canada trades with, are the details of the trade agreements that it operates through, and how those agreements were concluded.

Not all trade agreements are created equal

In addition to NAFTA (with the USA and Mexico), Canada already has Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Columbia, Peru, Costa Rica, Chile, and the European Free Trade Association in place and the implementation of agreements with Honduras, Panama, and Jordan expected soon. A dozen others are in negotiation including the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the 27 member European Union. There are 24 Foreign Investment Protection Agreements (FIPAs). However, devils always dwell in details.

The CIC report focuses on a critical distinction that differentiates successes from sellouts:

“The interests of a small, open country like Canada are best served by the broadest possible agreement with the largest number of partners. This is true because in large negotiations Canada is more likely to achieve results that would probably elude it in one-on-one negotiations; because a multilateral deal opens many markets at once instead of one at a time; and because it sets global ground rules for trade instead of creating a patchwork of sometimes conflicting obligations.”

“The interests of a small, open country like Canada are best served by the broadest possible agreement with the largest number of partners. This is true because in large negotiations Canada is more likely to achieve results that would probably elude it in one-on-one negotiations; because a multilateral deal opens many markets at once instead of one at a time; and because it sets global ground rules for trade instead of creating a patchwork of sometimes conflicting obligations.”

With a global export market share of 2.5 per cent, Canada is not a trade superpower. In one-on-one negotiations with the United States, China — or for that matter the European Union (Canada is negotiating CETA not as one nation amongst a club of 28, but as one very junior partner with the entire EU) — Canada is a bit player with little leverage for its genuine interests to be accommodated, or to achieve reciprocity. In other words, we get steamrollered. Those countries with which Canada can negotiate equitable, reciprocal terms tend to be equally small players on the global trade scene. Thus, the CIC report recommends that Canada eschew developing an overlapping patchwork of bilateral trade deals, and focus on multilateral or regional agreements that bring greater coherence to the market, open up larger areas of the globe, and put Canada on an equal footing with its trade partners.

The report’s other main conclusion is that Canadian firms understand the changing nature of trade. Increasingly, it is not the case that companies produce a product “lock, stock, and barrel,” but rather that they assemble goods and services in complex ways through what are know as value chains or value grids (also known as distributive or integrative trade). Companies can position themselves at the top of a chain (as Canadian manufacturers such as Research in Motion and Bombardier, or cultural producer Cirque du Soleil, have done) and/or plug specific goods or services into the value chains being assembled by others. If Canada wants to step beyond the traditional “hewer of wood and drawer of water” role that it has cast itself in, government and business need to understand the global value chains of their sectors, pro-actively take advantage of these, and be prepared to create imaginative new ones of their own.

Further FIPPA fibs

It’s worth underscoring that little of the above good advice holds true in relation to the China-Canada FIPPA, an investment agreement, which it appears will have Canadians over a bitumen barrel. In recent days the debate on this FIPPA has reached the boiling point. Spearheaded by LeadNow.ca, almost 67,000 Canadians have petitioned Stephen Harper to reject the treaty. New Democratic Party leader Thomas Mulcair has been adamant that “The Conservatives will not tie the hands of the NDP. We will revoke this agreement if it is not in the best interests of Canadians.” Green Party leader Elizabeth May said that the treaty “threatens our security, our sovereignty and our democracy” and will turn Canada into a “resource colony” of China. Meanwhile, interim Liberal leader Bob Rae is protesting the lack of transparency surrounding the agreement and why it requires 15 years advance notice to withdraw from it when the term specified in most trade agreements is a year or less. Such secrecy, he said, “creates suspicion in the public that there’s something to hide.”

And FIPPA, doesn’t only look like a rotten investment deal for Canada; it’s principle function will be to even further enrich the über-elites of the Chinese Communist Party that control its web of mammoth State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Back to Terry Glavin’s article The Canada-China investment protection racket:

“While China’s per-capita income hovers around that of sand-rich Turkmenistan, last year the net worth of the wealthiest 70 members of China’s laughably named National People’s Congress, by Bloomberg News’ calculations, was $89.8 billion. China’s nouveau riche know very well that the jig is up. Two surveys carried out in 2011 by China’s Merchant Bank and by Shanghai’s Hurun Institute found that roughly 60 per cent of China’s millionaires are already preparing for emigration or are planning to leave the minute a chance arises.

“While China’s per-capita income hovers around that of sand-rich Turkmenistan, last year the net worth of the wealthiest 70 members of China’s laughably named National People’s Congress, by Bloomberg News’ calculations, was $89.8 billion. China’s nouveau riche know very well that the jig is up. Two surveys carried out in 2011 by China’s Merchant Bank and by Shanghai’s Hurun Institute found that roughly 60 per cent of China’s millionaires are already preparing for emigration or are planning to leave the minute a chance arises.

“The Communist Party’s princelings have been plundering the country so ravenously that China’s financial institutions are starting to feel the shocks of capital flight. The China Economic Weekly reports that over the past 12 years more than 18,000 executives and officers of Chinese state-owned enterprises have been caught trying to flee with plundered funds. According to a study published just last week by the Washington, D.C.-based organization Global Financial Integrity, China’s elites squirrelled $472 billion out of the country last year alone. This isn’t socialism with Chinese characteristics. This is the Sopranos with Chinese characteristics.”

If Canada is not to become complicit in the resource plunder of our own country, as well as the corruption and economic plunder of other states, we need to have a political administration that understands there are ethical dimensions to trade. That equitable and fair trade can enrich people and their societies and bring prosperity and stability, but that poorly conceived, unfairly structured, inadequately regulated, and inequitably distributed trade can ruin the environment, squander resources, destabilize the climate, undermine social structures, and enrich the power elites and transnational corporations at the expense of the other 99 per cent of humanity. Back to Winnipeg-based freelance writer Frances Russell who captures this perfectly:

“[Harper’s] fixation with control and secrecy drives his government’s relationship with the provinces, with whom he largely refuses to meet, as well as the negotiation and conclusion of trade treaties, which he signs with abandon, and with virtually no parliamentary oversight, consultation or debate allowed. In fact, elevating corporate rights over the rights of citizens and their democratic institutions seems to be the Harper government’s core agenda.”

[Part 5 of this series is Superpower or Supermarket? The folly of foreign investment; Part 3 is Carbon attacks: The Harper Conservatives and the Canadian resource economy.]

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.