Calgary RCMP may have done Canadians a great favour by laying criminal libel charges against a man they accuse of running a website critical of Calgary city police.

With a little luck and the efforts of a capable lawyer, the Criminal Code offence of “Defamatory Libel” will end up on the scrapheap of history, where it belongs.

The Defamatory Libel provision of the Criminal Code and its Sharia-like sibling, Blasphemous Libel, have no place in the law books of a modern democracy.

On their face, these laws violate the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Specifically, our guarantee of “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.”

Moreover, by any commonsense definition, they cannot be defended by the Charter’s qualifying clause, which states that its protections are “subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

Adequate tools are available to the authorities and individuals to deal with obstruction of criminal investigations and defamations of police officers. These include the obstruction of justice provisions of the Criminal Code and the civil tort of defamation, which gives a police officer or any other person whose reputation has been besmirched the opportunity to sue for damages.

So if John Kelly of Calgary, who was arrested Thursday and also charged with obstructing a police officer from his duties, can find a lawyer willing to represent him, perhaps we can see Defamatory Libel proceed to the chambers of the Supreme Court of Canada for its long-overdue disposal.

Kelly’s website, according to the Calgary Herald’s prudently worded account, “accused officers of perjury, corruption and destroying evidence… Police deny the charges, saying they injure the reputation of Calgary police officers and interfere with an ongoing homicide investigation.” (RCMP are handling the case on the sensible grounds the Calgary Police Service ought not to investigate on its own behalf.)

The website is hosted in the United States, however. While, as the Herald pointed out, “RCMP can ask the New York-based Internet provider to take it down,” the Internet provider can also tell the RCMP its writ does not extend to New York State. Indeed, if memory serves, citizens of the United States established quite decisively in the late 18th Century certain limitations on the prerogatives of groups of men with the word “Royal” in their titles, mounted or otherwise.

The Internet provider may be inclined to do just this, owing to the fact that the country established after the rebellion of 1776 came to have, in the words of the United States Supreme Court, “a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

The Supreme Court of Canada would do well to consider the wisdom of the reasoning of that civil-rights era American case, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, when it eventually considers the criminal prosecution against Kelly.

In 1964, Times v. Sullivan turned the law of defamation in the United States on its head, one American innovation we would do well to imitate in Canada. And while it related to the civil tort of libel, much of the reasoning applies directly to Canada’s absurd and unconstitutional Defamatory Libel criminal offence.

Kelly has expressed strong views about members of the Calgary Police Service, which the RCMP says it can prove are false.

Times v. Sullivan, a case involving strong statements made about Alabama police officers in an advertisement, established in the United States the important principle that the plaintiff in a libel case (that is, the person who claims to have been defamed) must prove that the person who made the statement knew that it was false or acted in reckless disregard of the truth.

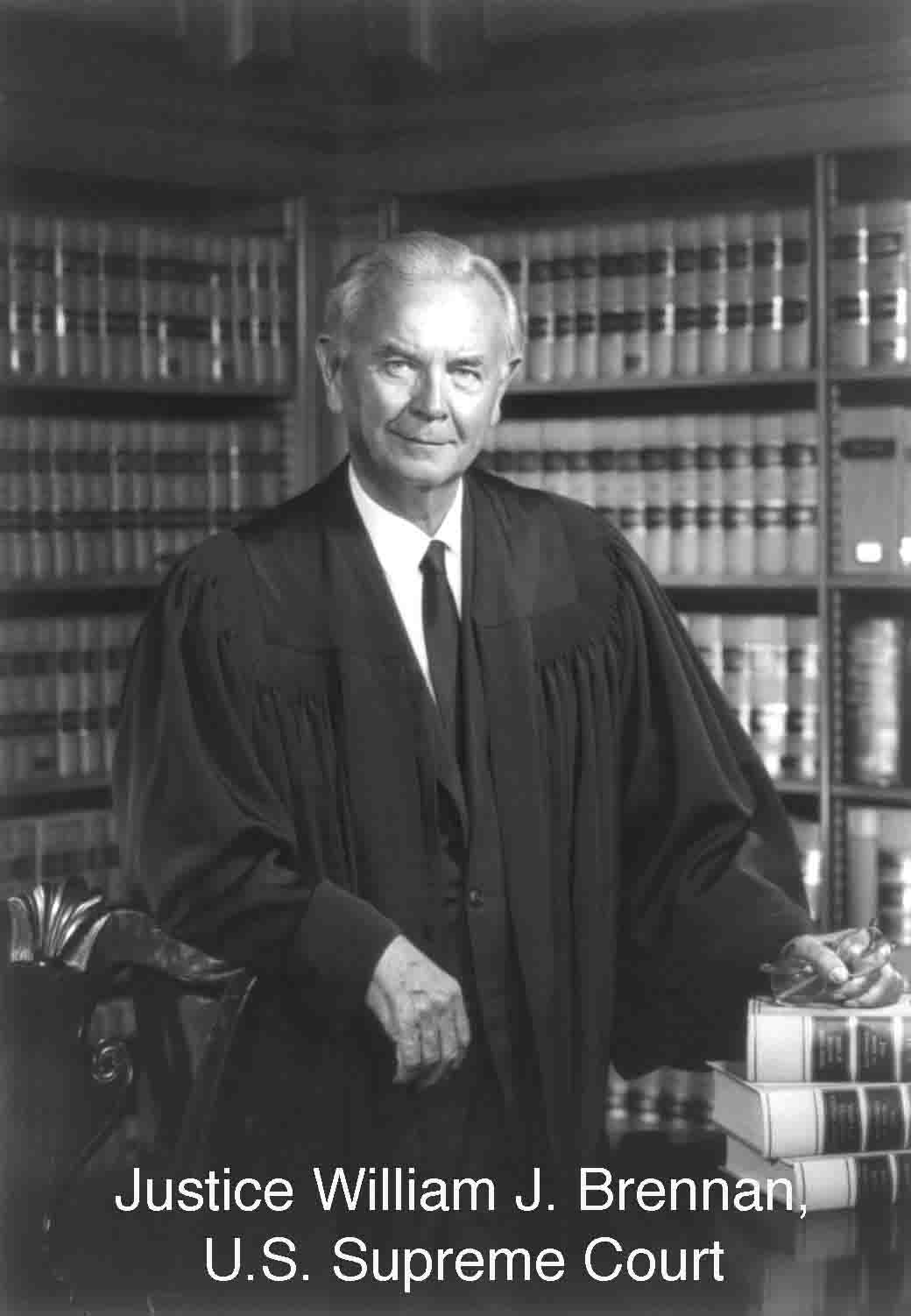

This was necessary, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. of the U.S. Supreme Court wrote, because erroneous statements are inevitable in the kind of strong debate on which a democracy thrives, and freedom of expression needs “breathing space” in which to survive.

The Supreme Court of Canada has already gone part way down this road, creating in 2009 the new civil libel defence of “responsible communication in the public interest.” While this new defence still holds journalists and others to high standards, it does recognize that minor errors made in good faith alone should not result in a defendant being held liable for defamation — as long as the story is in the public interest.

Significantly, the Court also noted in 2009 that cases involving police officers accused of acting wrongly are clearly matters about which all citizens should be concerned and therefore can automatically be defined as being in the public interest.

Obviously, Justice Brennan’s courageous logic extends to the outrageous idea of criminal prosecution of defamatory statements, especially those made against powerful people and groups in society.

Indeed, this is especially true in the case of Defamatory Libel since the mere existence of this law combined with the aggression and prosecutorial powers of the police and courts will inevitably exercise a powerful chilling effect on the willingness of citizens to make legitimate criticisms of the authorities.

It’s been 73 years since we last had the opportunity in Alberta to do something about Canada’s iniquitous Defamatory Libel law. But since Social Credit MLA Joe Unwin and George Frederick Powell, advisor to the Social Credit Board, served time at hard labour for calling for the extermination of bankers’ toadies, we have a new tool to defend our fundamental rights — the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Thanks to the RCMP, now is the time to complete this long journey and purge the Criminal Code of this insult to Canadians’ freedom of expression.

This post also appears on David Climenhaga’s blog, Alberta Diary.