The Canadian Senate has never had an obvious purpose.

The “fathers” of Confederation, who designed it 150 years ago, did not seem to have a clear idea as to what role they wanted their Senate to play.

In other federations — that is, countries with federal systems similar to Canada’s — the upper houses usually fulfill a “federal” function. They were designed to be the eyes, ears and voices at the centre for the federations’ “constituent units” — the states, provinces, or what have you.

There is a hint of that in the role of the Canadian Senate, but only a hint.

During the decade and a half of fevered constitutional activity that started with the run-up to the first Quebec sovereignty referendum in 1980, many demanded that the Senate be turned into a true institution of Canadian federalism.

Triple E: The Western demand

While Quebecers pushed for an asymmetric federation, one that would assign the necessary powers to their “distinct society” (a phrase that goes back to the original constitutional discussions of the 19th century), Westerners wanted a “triple E” Senate, on the American model.

Canada’s Senate, they demanded, should be elected, effective and have equal members for all provinces.

Triple E was a rallying cry of the Reform Party, of which Prime Minister Stephen Harper was one of the original class of 1993 MPs. (In fact, it was Harper who put the triple-E plank into Reform’s 1988 campaign platform.)

Even some non-Westerners have expressed enthusiasm for a more powerful, representative and “federal” upper house.

Claude Ryan, who led the Quebec Liberal Party in the 1980 referendum campaign, advocated that the Senate should be remade as a “House of the Provinces.”

Ryan’s idea was based not on the U.S. model, but on the German upper house, the Bundesrat, whose members are delegates of Germany’s constituent unit (“Länder”) governments.

The German upper house’s function is to vet federal legislation that might have an impact on the Länders’ role — which could include a lot of proposed laws.

If Canada had such a system, and the federal government were to propose new criminal legislation which the provinces would have to implement (such as increased mandatory minimum sentences), a Ryan-style House of the Provinces would be able to amend or even block it.

When the Quebec Liberal leader proposed his House of the Provinces, his federalist colleague, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, reacted the way Stephen Harper did to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

He acted as though it had never happened.

Sober second thought

There is another putative role for the Senate, the one envisioned by John A. Macdonald.

It is to be the chamber of “sober second thought.”

Liberal MP and former party leader Stéphane Dion has posted a well-reasoned essay on Senate reform on his website that, for the most part, does not overly tilt toward partisan advocacy.

In it, Dion cites the way in which, historically, the Senate has played that “second thought” role.

“Between 1994 and 2008, the Senate amended nine per cent of the Bills approved by the House of Commons and only explicitly rejected two out of 465 Bills.” Dion writes. “The Senate acted exactly how a Chamber of sober second thought is expected to. Year in, year out, it amended from eight to 10 per cent of the Bills proposed by the House of Commons and almost never rejected any.”

Dion explains that the Senate was able to perform this useful function because its members were not as involved in partisan politics as were their colleagues in the House of Commons.

He then bemoans the fact that Prime Minister Harper has imposed the same ironclad, partisan discipline on his Conservative senators as he does on House members, thus effectively stripping the Red Chamber of that historic “sober second thought” function.

A house of entitlement and privilege

There is yet another view of the Senate’s vocation that may be closest to reality.

The Canadian Senate, from this perspective, was meant to be neither a key feature of the federal system nor a legislative check on the House of Commons.

It was, mostly, designed to be Canada’s answer to the British House of Lords.

Lacking a true aristocracy, those colonial wannabes, the fathers of Confederation, decided to create an ersatz one — ergo, the fathers’ insistence that all Senators must own at least $4,000 worth of property, a princely sum in 1867.

Neither women (not deemed “persons”), nor working-class renters, nor tenant farmers were welcome in the Senate that Sir John A. Macdonald and his colleagues created.

From its inception, Canada’s upper house was essentially all about social class and privilege.

And it has not changed much in nearly 150 years.

Women were finally allowed in only in 1929, after the Famous Five took their historic case first to the Supreme Court (where they lost) and finally to the British Privy Council.

But non-property owners — and that includes the millions of Canadians who rent their homes, not to mention most Indigenous Canadians — are still not welcome.

And the principal qualification for admission remains prime ministerial whim, usually informed by partisan considerations, and not much else.

The scent of entitlement, snobbery and self-reward clings to the Senate, to this day, made only stronger by the reluctance of too many of these well-heeled political appointees to even pay for their own breakfasts (when partaking of what the airlines offer would be beneath their dignity).

That is why Canada’s traditional party of the left, first the CCF, and then its successor, the NDP, has always favoured a simple sort of reform: abolition.

How Mulcair could go about abolition without massive constitutional changes

Current Official Opposition and NDP leader, Tom Mulcair, promises that he will proceed with abolition if his party forms government.

That will not be easy.

It will require constitutional change, which, in turn, would require consent of the federal House of Commons and all of the provincial legislatures.

In the past, fundamentally changing any part of the constitution has been inevitably linked to other demands for major changes.

Quebec has not been willing to accept Senate reform unless it got its traditional demand for recognition as a distinct society.

Canada’s Indigenous people failed to get the self-government and recognition of their rightful place as full partners in the federation they were offered in the failed Charlottetown Accord of 1992.

That failure is an open wound on the Canadian federation, together with all the other affronts to Indigenous Canadians.

First Nations leaders do not have an official place at the constitutional table, but could Mulcair get away with abolishing the Senate without addressing their concerns?

Those are big and difficult questions.

Were he ever to get the chance, Mulcair might choose to address Indigenous concerns non-constitutionally, through the nation-to-nation approach he has promised.

And he might, just might, be able to convince a Quebec government to agree to Senate abolition without constitutional recognition of distinct society if he, again, were to pursue other measures that demonstrate respect for Quebec’s jurisdiction.

As prime minister, Mulcair could, for instance, repeal Harper’s federal criminal code changes that are obnoxious to Quebec, and only proceed with future legislative initiatives that implicate Quebec’s (and other provinces’) role on a cooperative, consultative basis.

In other words, if an NDP government were to set an entirely new and much more open tone in its dealings with Indigenous Canadians and with the provinces, that might make it easier for all concerned to go along with what would likely be a popular move: rolling up the Senate’s red carpet for once and for all time.

As well, as it proceeded to abolish the Senate, a new government could also move to enlarge the House of Commons, by including added members who were elected proportionally.

An NDP government might even consider mandating a minimum number of Indigenous MPs, something the New Zealanders have done with some success.

In other words, Senate abolition could be linked both to a renewed spirit of federal cooperation (which fully includes First Nations) and a program of genuine democratic reform.

That could make it acceptable to all — to use the currently all-too-fashionable term — stakeholders

It may be a tall order, but it would sure beat the status quo.

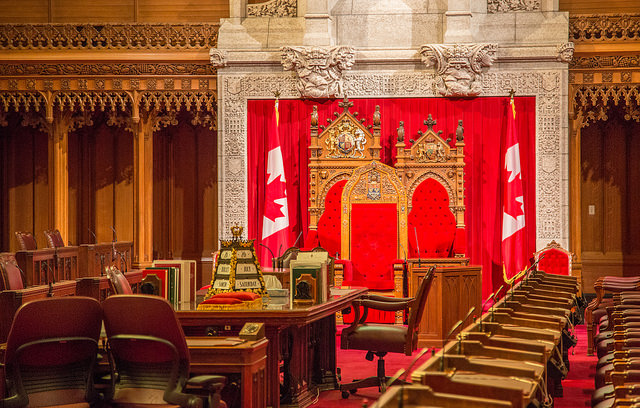

Photo: flickr/ Tony Webster