In the preceding entry, we saw how the Conservative Party supporters or agents who in 2008 engineered Minister of Natural Resources Gary Lunn’s re-election through robocall fraud got away with the crime scot-free; and we noted some of the deficiencies in Elections Canada’s investigation in the 2011 ground-zero riding of Guelph. Let’s consider now some of the more substantive failings in the investigation of the 2011 vote-suppression fraud.

In what promised to be a major breakthrough, Elections Canada investigator Allan Mathews used information supplied under court order in late 2011 and 2012 by the Conservative-affiliated voice-broadcaster RackNine to track down the Internet Protocol address and the modem used in organizing the “Pierre Poutine” robocalls that had victimized opposition-party supporters in Guelph.

But having found the modem, which was rented from the communications company Rogers, Mathews was stumped: it served an open wifi connection in a house southwest of Guelph that was shared by people who had no knowledge of or interest in politics. If “Pierre Poutine” had accessed their unprotected wifi connection from a car parked outside the house, then he remained untraceable. Accordingly, news stories announced that Elections Canada’s Guelph investigation had run into a “blank wall.”

But Rogers recycles its modems — and during the 2011 election campaign that same modem had provided internet access in the campaign office of Marty Burke, the Conservative Party’s candidate in Guelph. Mathews had made an elementary error: like someone whose winning lottery ticket collects lint at the bottom of a laundry basket, he had won the jackpot without realizing the fact.

The headlines that should have reported a sensational breakthrough — namely, the discovery that “Pierre Poutine” had organized his fraudulent robocalls from within the Conservative Party’s Guelph campaign office — carried instead a message of frustration and bewilderment. And by the time Mathews’ error was corrected, months later, the corporate media either missed the story or decided not to make a big deal out of it. Most Canadians thus remain unaware that “Pierre Poutine” (who in his contacts with RackNine called himself “Pierre Jones”) was not some lone maverick doing his dirty work alone and in the dark, but rather a person with free access to the office and the computers of the Conservative Party in Guelph.

Nor is it widely understood how incriminating the material evidence is that Mathews obtained from Matt Meier, the CEO of RackNine, in the form of detailed information about the session logs that recorded customers’ access to RackNine’s servers. These session logs, summarized in paragraphs 167-69 of an “Information to Obtain” document filed by Mathews on March 20, 2012, reveal that during the 2011 election campaign there was a close relationship between two of RackNine’s clients: Client 45, who was Andrew Prescott, the Deputy Manager of the Guelph Conservative campaign, and Client 93, “Pierre Jones,” who falsely claimed to be a student at the University of Ottawa.

Prescott and “Pierre Jones” contacted RackNine from the same two Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. “Pierre Jones” logged in to two of Prescott’s voice-broadcaster sessions, and Prescott actually stored three sessions under the name “Pierre Jones.” Finally, on two occasions on election day, “Jones” and Prescott logged in within minutes of each other from the same IP address. It seems clear that they were either one and the same person, or else very closely acquainted.

Another breakthrough in the case? Don’t hold your breath.

For Conservative Party headquarters, no less, had nominated another person as chief perpetrator of the crime. In late February 2012, public concern over the telephone fraud had been re-ignited when investigative reporters Glen McGregor and Stephen Maher revealed that Allan Mathews had identified RackNine, which had done communications work for many Conservative campaigns, including Stephen Harper’s, as the source of vote-suppression calls sent into Guelph on May 2, 2011. Within days, senior people in Conservative Party headquarters had given the name of Michael Sona, a Conservative staffer who had been Marty Burke’s communications director during the 2011 campaign, to Sun News, their in-house propaganda service — and Sun journalist Brian Lilley, without giving Sona any chance to comment, made the accusation public on a lunchtime television broadcast.

Unlike Prescott, who boasted of his skills, Sona had no IT or cellphone expertise, and he was not one of the five members of the Burke campaign who had access to the CIMS database. The evidence against him consisted for the most part of claims by other Conservative staffers, including Prescott, that on one or another occasion, either on election day or shortly afterwards, Sona had boasted to them of having organized the robocalls fraud.

These claims seem in several respects dubious. None of the witnesses came forward until after Sona had been denounced by the Conservative Party, and on some important matters of fact their statements were incorrect. Moreover, several of the staffers were produced for Elections Canada investigators by Conservative Party lawyer Arthur Hamilton, who also attended their interviews with investigators (though representing the party rather than the witnesses). During those interviews, Hamilton’s prompting led the investigators to ask one witness whether she had been coached.

Not merely was Sona charged on the basis of this rather sketchy evidence, but Prescott — despite the material evidence pointing to his involvement in the fraud — was granted immunity from prosecution in order to testify against Sona. The ensuing trial was marked by elements of farce. Although the judge and crown attorney agreed that the testimony of Prescott was unreliable, inventive, and self-serving, the judge rejected arguments that the other witnesses’ evidence was tainted. Sona was convicted, finally, not of organizing the robocalls, but rather of aiding and abetting a crime committed by persons unknown.

Sona’s lawyer, at one point in his cross-examination, made Prescott read aloud a message he had sent to Sona in July 2013, when the two were still on speaking terms. Prescott wrote, in part, that the telephone fraud scheme “was clearly wide-spread, national, and well organized….it’s painfully clear to all now that the [Conservative] Party is now seeking to misdirect Canadians by accusing ‘local staffers’ of what was a national crime.”

One may suspect that Prescott shared some version of this message with other people in the Conservative Party — as an implicit threat that should he be charged, he had stories to tell. It seems possible, conversely, that Sona was charged and convicted because he had no comparable means of defending himself.

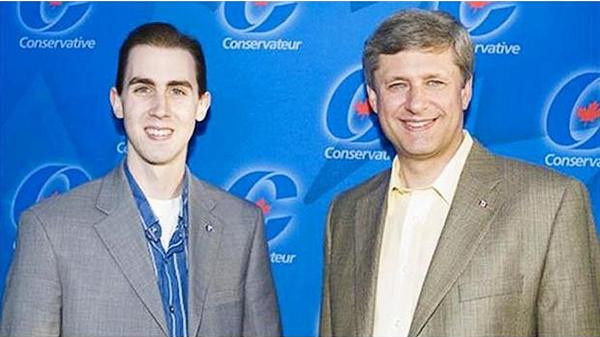

Image: Twitter