After I return from a trip to Haiti, I am often asked, “How are things in Haiti now?” Last week I returned to Haiti, and on this trip, it’s particularly difficult to respond.

When you get off the plane, there are signs of progress. The airport has been renovated. The roads around Port-au-Prince are being repaired.

For those in bright T-shirts on their way to the provinces, travel times have been considerably reduced. Stopping en route in a guarded, air conditioned restaurant or supermarket offers the appearance of relative affluence with customers stopping to inspect shelves full of packaged imported food. If one has the funds, a private vehicle and the inclination to go to a night club or restaurant in the affluent Pétion-ville, the trip home is safer, since large parts of Route de Delmas — a main thoroughfare — that now has solar lighting.

Many new light posts are adorned with pink posters alternating in French and Creole celebrating Haitian President Michel Martelly’s two years in office. One in particular asks “who has done better in the past 25 years?”

Before his career in politics, Martelly was a performer, known as “Sweet Micky,” (in)famous for his ribald lyrics and stage antics, including dropping his pants. Now, as head of state, he is performing progress, most recently to new Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro last Tuesday. Port-au-Prince was all decked out: the route from the airport was adorned with Venezuelan flags and signs saying Bienvenidos y muchas gracias.

These new signs sit next to ubiquitous banners that begin with pouvwa pèp la (the power of the people) has accomplished this or that thing: increasing the number of children in school, “helping poor for the first time,” repairing the airport, etc. often punctuated with the phrase tèt kale, Martelly’s slogan, a play on words noting his bald head but also meaning no bull.

The performance appears to be working, with positive reviews from official development agencies, NGOs, foreign governments, mission groups, many in the Diaspora, middle class and even some within Haiti’s poor majority, like my neighbor who has a job as a driver for the government.

For those with a certain means and/or on a short visit to the country, things do indeed appear to be getting better. But a closer look shows the cracks in the otherwise smooth veneer of progress.

Perhaps the best analysis comes from a fellow performer. By far the song from this year’s Carnival repeated most on the taptap (public transportation) and people’s lips is by Don Kato/Brothers Posse, Aloral. The song’s lyrics deconstruct the Martelly administration’s many public pronouncements as aloral, idle talk. People from all walks of life repeat this term to question the many overblown promises, about education, job creation, etc…

When I asked people from all walks of Haitian life who were extolling the progress, no one could identify the source of the public works projects, the company, donors, etc. One reason could be the absence of billboards or large signs typical in this “Republic of NGOs” listing the name, donor, duration, cost, and executing partner of the project, complete with NGO, foreign donor, and Haitian ministry logos.

Another explanation is that the progress began before. A commentator within the Haitian government pointed out that most of these projects began well before this current government took office. “So Martelly gets to claim credit for everything.”

Putting aside the question of who deserves credit for the improved conditions for the relatively well to do, Frisline spoke for many when she said, “hunger is killing people in [camp] Karade.”

Lavi chè (high cost of living) is a preoccupation for many people. For example, a small bag of rice used to cost 400 gourdes in 2004 (about $10). Today it’s 1250 gourdes. When people took to the streets in 2008 it was 600.

Why aren’t they now? A community leader in Delmas explained that it is because of Martelly’s effective PR machine, unlike the silence of former President Rene Préval. According to this leader, “Five percent of the population is living better, the people anwo [above, in the suburbs of Pétion-Ville, Laboule, Thomassin, or Kenscoff]. They just send rain and the trash down to the city, to the pèp.”

Another indicator was Mother’s Day at the end of May. No one bought flowers in the streets because they couldn’t afford to, so people didn’t even bother to sell them.

For those who don’t know to look for these signs, the streets devoid of both potholes and timachann (small merchants) are a good thing. On a trip to Delmas, I saw a truck of nine heavily armed individuals, only three of whom in uniform, destroy timachann stands, one plainclothes person even taking expensive merchandise like cell phone chargers and padlocks.

One major indicator of a slow burning crisis is the gradual departure of NGOs and foreign employees. If you walk the streets and take public transport, and can speak the language, you can hear people talking about the lack of jobs as NGOs leave. If you are also a blan (foreigner) you’re likely asked for a job with increasing frequency and desperation.

NGO employees earning five to twenty times their Haitian counterparts drove up prices for housing and luxury items. Behind armed guards, supermarkets are still stocking Pringles, which can go for $4 per can. And prices for housing are still, unbelievably, going up, which doesn’t even include the plummeting value of the Haitian gourde against the U.S. dollar, approaching 44 to 1.

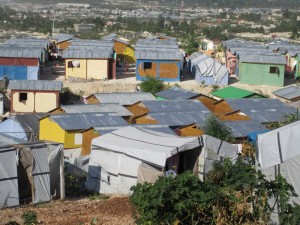

Importantly, to claim that the emergency phase is over is to deliberately ignore the many still living under tents. According to the International Organization for Migration, 320,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) remain scattered in camps that have one thing in common: their invisibility.

My neighborhood of Christ-Roi is saddled in between two very large camps: KID (referring to a political party that had its office there, after it was abandoned by a tonton makout) to the south and one of many named “Acra” (for the wealthy family that owns the land) to the north.

Both camps sit atop a major roadway from downtown to Pétion-Ville. With the progress in the roads, cars can go faster. The lights on Delmas or on the amazing new Catholic school built within months cast shadows on the entrances to the camps, rendering them more invisible. Passersby on foot — not to mention the residents who live there because they have no other choice — can’t help but notice the smell of years of neglect. Pointing to the forty-foot pile of trash meters from his makeshift tarp, Maxon, an artist living in Acra, said “No one has ever come by. They might as well just throw us on top of that heap.”

Of the eight camps in my 2011 study, only two remain. HANCHO I, at the outskirts of privately owned factories where goats roamed the trash and cactus-like vegetation, was finally closed, to make way for a new factory. The perimeter of the private property is already walled in. According to resident leaders, the Red Cross facilitated a relocation plan for most of the residents. However, 16 tents still remain, scattered across the camp.

Residents in Kolonbi, on the other edge of Haiti’s industrial park, are degaje yo, just getting by. But it has been months since a visit from any aid agency.

On the positive side, they’re not threatened by forced eviction, unlike 73,000 others according to the U.N., (Amnesty International documented 1,000 families for this year alone), from camps like ACRA I and II and Gaston in Carrefour. There’s no word at all from Kolonbi’s landowner, a former Army officer. Once in a very long while security agents come by to check things out but there’s no pressure to move. However, according to resident leaders, the Red Cross left after their work to reinforce the ravine. OIM’s gone. Oxfam’s gone. The horrible stench of rotting feces remains. And the water tap that was finally providing water after months of advocacy has again been turned off.

Karade, high on the hill overlooking the U.S. Embassy and the Aristide Foundation, seems to be stabilizing. During my visit in May, Karade had many more cars, motorcycles, and small boutiques than my previous visit in December. More houses have been made more permanent with tin roofs. There are more trees, and they sprout higher. It seems on its way to being a permanent settlement, except for one problem.

Deputy Anel Belizaire of Tabarre-Delmas (Veye Yo party, a splinter of Aristide’s Fanmi Lavalas) has been on the radio within the last couple of months saying that Toto wants his land back, and that people will have to move. A bunch of graffiti was written all over the front entrance, for the people relocated from St. Louis de Gonzague, where all the electricity and temporary shelters have been invested, saying that the people will not move, that Anel is employing a particular set of vagabonds to commit acts of violence, and that the people are ready to mobilize.

‘Veye yo’ means ‘keep your eye on them’. Residents are keeping their eye not only on Belizaire but the two institutions.

According to Reyneld Sanon of FRAKKA (the Reflection and Action Force for the Housing Cause), Aristide declared the area a public utility during his 2001-4 term, possibly to expand upon his university campus. But Belizaire publicly declared that he personally negotiated with Toto about the land to help people after January 12.

While residents in Karade are negotiating with the government for land title, all is not well. In addition to lavi chè, water remains a dire problem. The only spigots are on the Tabarre side of the border owing to greater collaboration with DINEPA, the water and sanitation agency. But this was before Martelly revoked all but two city governments (including Delmas, where Karade sits and whose mayor Wilson Jeudy demonstrated hostility to IDPs).

None of this is to diminish the real progress that is highly visible, especially to foreigners. Indeed, those of us in solidarity need to take account and shift our narrative. However, the progress has its share of victims.

On Saturday, the recently-finished road in my neighborhood was again blocked. Not by trash or potholes this time, but by burning tires and scores of angry timachann. They demanded that the Haitian government have a formal burial for all eight people who died on June 14, as a Public Works truck careened down the hill following a brake failure. Three died on the spot, another three on their way to the hospital and two there.

I knew one of the merchants, Audanie, a single mother in her mid-forties who made anywhere from $1-3 profit a day selling hair care products. According to her friend Renete who sells next to her stand, Audanie’s three children sou kont bondye, are in God’s hands. Audanie’s death — as well as her life — unfortunately does not count. A banner made and hung up by the neighborhood organization honoring the three timachann who died right on the spot was taken down (by the police, say residents).

This dual reality in Haiti puts into question the model for development. Haiti is on its way to becoming Jamaica, or Latin America in the 1990s. Under right-wing dictatorships supported by the U.S., there was progress for the middle class. The few resources flowing through the pinch of structural adjustment were directed upward, but the poor became poorer as the societies became more unequal.

In other words, the situation in Haiti is in many ways like before the earthquake, with extreme poverty, inequality, and exclusion, but this time — like the camps in my neighborhood — hidden in shadows.

As a performer, Sweet Micky — who called himself the “president” of konpa — depended on a willing audience. The gag gets old after a while, forcing him to keep upping his game. Now that he’s president of Haiti, Martelly has several institutions which, for reasons of their own, are willing spectators to the performance.

As Don Kato asks, “Poukisa bilan gen gou lanbi nan bouch ou, epi nan bouch pèp la, se fyèl? Tèlman gen grangou?” Why do the official reports have the taste of conch in your mouth, but in the people’s mouths it is gall, because truly they’re hungry?

This article was originally published on The Haitian Times, June 30, 2013. Mark Schuller is assistant professor of Anthropology and NGO Leadership Development at Northern Illinois University and affiliate at the Faculté d’Ethnologie, l’Université d’État d’Haïti. He is the author of Killing with Kindness: Haiti, International Aid, and NGOs and co-editor of three volumes, including Tectonic Shifts: Haiti Since the Earthquake.

And here is recent, additional information on the humanitarian situation in Haiti:

* OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, June 2013 (five pages)

Among the items reported in this latest bulletin by the OCHA (Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs–UN) office in Haiti:

– Heavy rains in June killed six people and otherwise affected nearly 7,000 people in three departments.

– The number of new cholera cases in June 2013 was 4,713, a rise of 40 per cent compared to May.

– Ongoing drought conditions in some departments have created food shortages affecting seveal million people and causing sharp price rises.

– Threats of evictions of survivor camp residents are ongoing, and conditions for many continue to deteriorate.

* Survivor camp numbers decline

The most recent International Organization for Migration numbers on survivor camp residents have been published. As of the end of June, 278,945 internally displaced persons are still living in camps. From the report:

“When compared to the previous report (March 2013), a 13% decrease is observed both in terms of IDP household and individual population. This rate of decrease almost doubles that observed in March 2013 and is the highest since April 2012.”

“About 89.6% of the observed reduction in IDP households is due to return programs offering rental subsidies carried out by various partners, followed by IDPs leaving sites for returning home or for unspecified reasons (10.3%) and 0.1% as a result of eviction.”

The 14-page report is available here: http://iomhaitidataportal.info/dtm/index2.aspx.

This was a guest article by Mark Schuller.