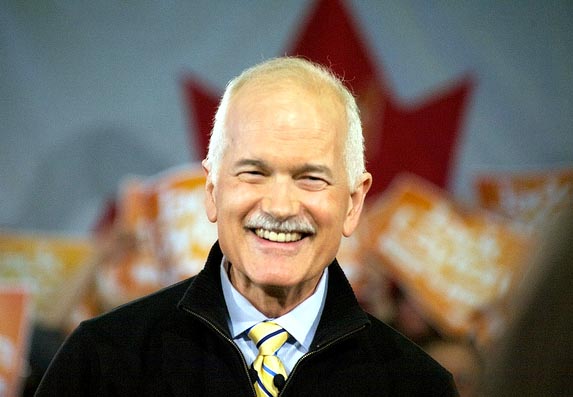

In 2003, when Jack Layton was chosen NDP leader, he and his party faced three virtually insurmountable obstacles. His good humour, positive attitude, and considerable abilities were about to be tested.

To say the federal NDP had serious organizational shortcomings was an understatement. People became members of the federal party only by joining the provincial party. So the federal party had no membership list of its own. It had loyal supporters, but was donor poor.

At election time, the federal party office relied heavily on provincial party staff to run its campaigns. Losing party status in the federal parliament — in the voter rush to get rid of the Tories a decade earlier — had deprived the small federal caucus of staff and resources. The only decent recent results for the federal NDP came in Atlantic Canada, where Layton’s predecessor, former Nova Scotia leader Alexa McDonough, brought the party to life. In other places, notably Ontario, association with a provincial NDP government was bad news for federal candidates.

In his leadership run, Layton had exhibited impressive modern organizational smarts. His campaign manager, Bruce Cox, and fundraiser, Bob Penner, were top quality. The interest in nuts-and-bolts organizing looked promising to long-time NDP members. They were not disappointed. With some help from favourable federal party financing legislation introduced by Jean Chrétien, Jack Layton and his people were able to put federal party organizers into the field on a full-time basis. Purchasing an Ottawa office building that also served as its headquarters gave the party an asset that could be mortgaged for funds to fight an election. Under Jack Layton the party could raise money, and as it showed in each succeeding election, increase the number of Canadians voting NDP each time.

While Canada is not exactly two countries, it does have two official languages, and many Canadians are locked in their own language world. This includes MPs, journalists, public servants, and of course, citizens. For most of its 50 years, the NDP was an Anglo effort. Not only did it have little exposure in Quebec, without a Quebec presence it had reduced credibility outside Quebec. By winning 59 seats in the province where he grew up, Jack Layton was able to turn this situation around in a way no one thought possible. How he did it will be debated for years.

As if resolving serious organizational issues and winning a majority of Quebec seats were not enough, Layton faced down another major challenge. “Serious people,” those who have real money, own newspapers and media outlets, and who play leading roles as opinion makers, enjoyed dismissing the NDP out of hand. The NDP had never formed a government federally, and was the fourth party in parliament. Jack himself did not have a seat.

As the old French socialist saying goes, there are only two realities, death, and the class struggle. For the rich and powerful, and the wannabe rich and powerful, Jack and his ilk were on the wrong side of the divide.

Layton brought his considerable experience as a Toronto city council member and urban activist to federal politics. He knew what issues could be used to penetrate the post-Reagan revolution knee-jerk anti-NDP attitude among the media. He also knew enough to stay away from issues that would allow others to typecast him as an out-of-touch socialist. This need to surprise brought other problems. The out-of-touch socialists wanted Jack Layton to spread the good word (because they were right, and the CEOs were wrong), not just deliver a zinger for the national news.

The Layton strategy for bringing the NDP into the national conversation was grounded in his red/green politics. When he ran for leader of the NDP, his passionate concern was that Canadians be able to conserve energy, retrofit our cities, and change the way we live. Climate change was on his mind. Elected to parliament, he thought he could get Stephen Harper to understand the importance of global warming. He even gave him a book on the subject.

Reaching out to people, getting to know what they were thinking, opening a two-way dialogue (even with serious adversaries) was what characterized Jack Layton as a leader. Canadians had Jack right. He was the guy to be with for a beer, or to share a bottle of wine. He enjoyed himself, and was easy to like, as people guessed. He wanted to share his thoughts — after he had heard from you first.

Many of us will remember where we were last August 22 when it was announced Jack Layton had died. His loss was felt deeply by people for many different reasons. His courage in fighting an election while getting around with a cane after a hip operation, touched people who rejected his politics. His NDP supporters remember his sickly appearance at the press conference announcing his cancer was back, and treasure the memory of his letter to Canadians.

In his dying, as in his political life, Jack Layton connected with people. He is missed.

Duncan Cameron is the president of rabble.ca and writes a weekly column on politics and current affairs.