Like this article? Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Finance ministers of the 19 Eurozone countries (the Eurogroup) are making life difficult for their Greek counterpart, Vanis Varoufakis. Despite being ranked first by the OECD in implementing reforms, Greece is last in economic growth. No matter, the Eurogroup argues Greece should continue with IMF measures it agreed to in 2012, and that have contributed to financial ruin.

The Greek finance minister wants the suicidal policy course imposed on his country to end. Absurdly, Greece was expected to triple the amounts it is now paying its creditors.

Last Friday, the Eurogroup agreed to continue to provide bridging finance to Greece for a four-year period, and loosened the debt repayment conditions. Ministers also accepted that Greece would write its own reform plan, but asked to approve it, which was not helpful.

Uncertainty surrounding Eurogroup negotiations has contributed to massive deposit withdrawals imperiling the Greek banking system. Instead of working to ensure financial stability, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been doing the opposite, withdrawing borrowing power from Greece, then handing out liquidity after precipitating unease among Greek bank deposit holders.

With the ECB about to start its own version of U.S.-style “quantitative easing” or printing money to buy its governments bonds — a risky undertaking — provoking a run on the Greek banks hardly seems smart.

The nature of the European financial crisis has been obscured by domestic politics and silly national stereotyping. As Michael Pettis has pointed out, the European economy is made up of sectors, and they can become unbalanced.

In northern Europe (Germany and Holland), the banking sector ran up large surpluses (in part because workers had made wage concessions), and it loaned heavily in Mediterranean real estate construction.

Northern money flowed south, including into government bonds. Spain became the second-largest destination for foreign investment in the world, Greece the fifth largest. When the world financial crisis hit, real estate investments went bad, and southern European governments (Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece) had difficulty making interest payments.

The world banking system got massive bailouts. In Europe this took the form of transferring private bank loans to EU institutions. The banks got bailed out, but not governments that had taken on debt.

Much Greek government debt to private banks was transferred to the ECB and European Union financial institutions. This was the Greek “bailout.” The Greeks still owed money. The northern European private banks had been let off the hook.

After Greek government debt to the private sector was restructured in 2012, it represented only 12 per cent of the total Greek debt.

Charles Dallara, the former chief negotiator for the private financial actors in that debt renegotiation is calling on the troika (made up of the ECB, the European Commission, and the IMF) to restructure and forgive Greek debt owed to the troika itself, and EU governments.

Indeed, Dallara blames the unwillingness of governments, the EU, and the ECB to provide debt relief for the sad state of the Greek economy today.

He told Euromoney magazine: ” There is a material risk of destabilizing the Greek financial system….”

The financial markets recognize that the Eurogroup policy of economic growth through debt reduction is preposterous. Led by an obviously out-of-his-intellectual-depth German finance minister, the Eurogroup is ignoring the basic rule of finance: when debts are too onerous to be paid, they will not be paid.

Debt relief works best when it is done immediately, and completely. Such was the case in 1953 when the Federal Republic of Germany received large-scale debt relief, an operation recalled by Varoufakis that deserves to remembered by a wider circle than those who benefited at the time.

Varoufakis has strong economic arguments working for him. All of Europe is suffering from deflation — forces of economic contraction. As families, companies and government simultaneously attempt to pay down debts, the European economy weakens. Greeks have suffered more than others from this “debt deflation” — paying debts instead of spending or investing — because Greece has succeeded most in cutting government spending per capita and squeezing the economy.

The outcome of the prolonged negotiations between Greece and the Eurogroup must be something the Greek government supports, and can ask its population to support. Otherwise the negotiations will have failed. However, the ad hoc, haphazard procedures adopted in Europe for the negotiations with Greece could well end in tragedy.

Duncan Cameron is the president of rabble.ca and writes a weekly column on politics and current affairs.

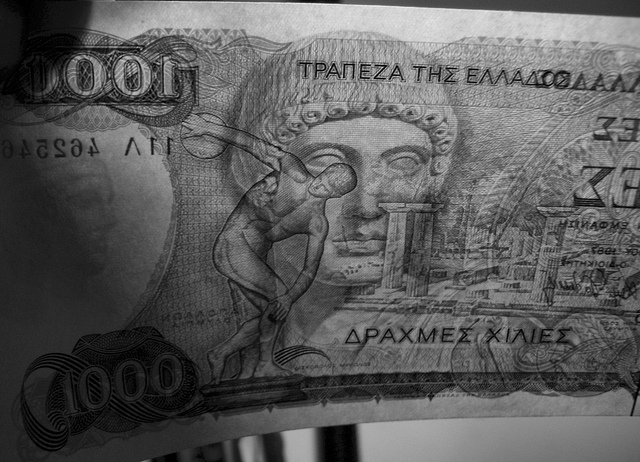

Photo: Pictoscribe/flickr

Like this article? Chip in to keep stories like these coming.