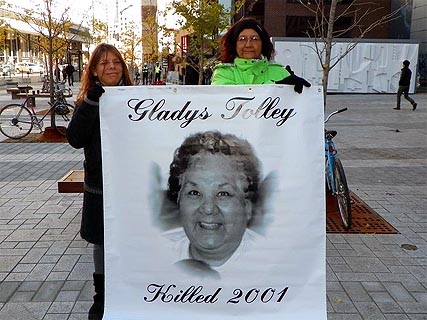

Bridget Tolley is an Algonquin grandmother of five from the Kitigan Zibi reserve in so-called Quebec. On Oct. 5, 2001, Her mother Gladys was struck and killed on the reserve by a Quebec Police cruiser. Since then, Tolley has been fighting for accountability, seeking justice for her mother.

On March 18, three days after the International Day Against Police Brutality and two days before the International Day for the Elimination of Racism, Tolley spoke as part of a panel at the Ottawa Forum on Police Violence, Incarceration, and Alternatives. Also part of the event was Ashton Alston, a former Black Panther Party member and ex-political prisoner, Julie Matson, whose father was killed by Vancouver police in 2002, and Jaggi Singh, a Montreal-based organiser and activist. Earlier in the day Tolley spoke at an afternoon vigil on Parliament Hill for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

There has been no admission of wrongdoing on the part of the Sûreté du Québec. What there has been is negligence and impunity.

From the very beginning, when Tolley tried to get a copy of the police report from the night of her mother’s death, she was forced to fight every step of the way.

“I thought they would have given it to the family, but they don’t,” she said in a phone interview. “I had to pay for mine and I had to also get a lawyer because they didn’t want to give it to me. It took me almost 13 months.”

Even on the night of the killing, “none of the police ever talked to us.”

When the family finally got the autopsy report, it was riddled with inaccuracies such as a statement claiming the family had identified the body. However, as Bridget says, “that’s not true.” As it turns out, no one in the family was ever permitted to see the body.

One of the most shocking things that the report revealed is that the lead investigating officer for the killing was, in fact, the brother of the officer who had been driving the car that struck and killed Gladys Tolley. “I definitely knew there was something wrong there,” says Bridget. “This is a conflict of interest.”

One of the central troubling issues is that, other than the doctor who declared Gladys Tolley deceased, only the police had access to the scene of the tragedy. “My people should have had jurisdiction to protect the body and the scene and this wasn’t done.”

The coroner who filed the autopsy report apparently never saw the body either. “The only people to see my mother after they struck and killed her were police, just police, and it was just like one big cover up. This is what happened and this is why I’ve been asking for an independent investigation.”

“I asked Quebec and they refused last year,” Tolley says. “I feel there is a lot of conflict of interest with the Province of Quebec.” She feels this way because all three forces that were involved — the reserve police, the Montreal police and the Sûreté du Québec — are all on the provincial pay roll. So when the Province was faced with the question of whether or not to undertake an independent investigation, as Tolley says, “of course they are going to say ‘no’.”

This is why Tolley is now focussing her fight on the federal government, trying to get them to overturn the decision from the provincial level, and find justice and accountability for what happened to her mother after almost a decade.

For Tolley though, it’s not just about her own struggle. “It wasn’t just my mother they were forgetting about,” she insists, “they were forgetting about all the women.”

Tolley has worked with the Sisters In Spirit project, a campaign of the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC). Since 2005, the project has gathered statistical information on violence against Indigenous women, revealing shocking trends and rates of violence. However, the Harper government has shut down the Sisters In Spirit project. This came amidst a series of other cuts to services and programs for Indigenous people and communities.

“This is one thing the government was trying to do is silence us again by not funding the Sisters In Spirit,” says Tolley. “I thought that they were making us disappear again.”

But, she says that she intends “to make sure to let the governments know that we are here and we are the families of the Sisters in Spirit and we are not going anywhere and we plan to remember them and honour them and not to let anybody forget about them.”

In 2010, NWAC was told that they could no longer organise the Sisters In Spirit campaign, and that they could not even use that name on or for any other project or educational material. This was the same year that the government budgeted $10 million to go towards projects to help on the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. However, the vast majority of that money is going into generic projects of the so-called justice system, and much of that directly to the RCMP.

Tolley suspects that one reason the federal government has, as she puts it, “killed the database,” is to prevent the alarming statistics around the numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women from continuing to be documented.

This past Friday in Ottawa is not the first time that Tolley’s work has brought her into spaces like the Forum on Police Violence, Incarceration and Alternatives. Last year she was involved in a similar forum in Montreal.

She tells a story from that event where she met other families from other communities struggling for justice and accountability after family members were killed by police.

“It was really something to go sit there with five other families; every time one of us told our story it was like I was telling my story over and over and over again… It was really something to meet these families and know how each other feels ‘cause we all have the same story.”

The statistics collected by Sisters In Spirit report that, across the country, more than five hundred and eighty Indigenous women have gone missing or were murdered since 1980 (some estimates say as many as three thousand), more than two hundred and twenty five of them since Bridget Tolley’s mother killed was ten years ago. That is far too many times for this “same story” to have to be told. But the truth is, even once is too many.

Alex Hundert has been an organizer with AW@L, the KW Community Centre for Social Justice and the Six Nations Solidarity Network and also involved with community radio and other forms of independent journalism. He is currently a defendant in the G20 conspiracy case and is now in Toronto under house arrest.