It’s membership time. Cultivate Canada’s media. Support rabble.ca. Become a member.

In April Firdaus Kharas told the Global Health and Innovation Conference at Yale University about his work, about how animation is one of the best tools to promote social justice around the world. He wondered why a medium so open to humour and cultural acceptance has rarely been used by professionals. Perhaps, he mused, “doctors should stay with being doctors and not try to be mass communicators.”

Sixteen years ago he said the same thing about bureaucrats, and it spun him onto the path of public service announcements (PSA) that would help shift how the world talks about health.

In the early 1990s Kharas was working for Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Board. It trained him in systems and reactions, and provided uncomfortable glimpses into the darkness of the human soul. But bureaucracy doesn’t create change, at least not the kind that human rights advocates thought would be more evident as the new millennium approached.

So he left, making a surprising jump to television because “I couldn’t see a better way to influence people. I’m completely a capitalist, a director and producer, maybe a social innovator.” Mainly he wanted to reframe how cultures thought about global issues. But first he’d have to make a living.

He named his company Chocolate Moose Media in 1996 and chose Singapore and Malaysia for early productions: a children’s TV series (Let’s See, Let’s Learn) and Malaysia’s first English-language adult soap opera (City of the Rich). He returned to Canada to produce Genie-Award-winning moves like Such a Long Journey and more animated children’s TV like Daft Planet and For Better Or Worse.

Yet the industry’s commercial emphasis was more irritant than lubricant. “I was asked to do a ‘Big Brother’ and said not unless you let me do it with six Israelis and six Palestinians.” Even in satire Kharas is fueled by social justice.

It came from his mother, an NGO worker in 1960s Calcutta, where Firdaus grew up as a middle-class Parsi. She took him to Mother Teresa’s hospice and taught him that a good life meant creating positive impacts by using one’s own resources. His Master’s thesis at Carleton University was on the state’s use of torture, perhaps a little prescient for 1980.

“All my work has ever been based on is the notion of universal values and that all humans have fundamental rights, not just because of their citizenship,” he says. With Chocolate Moose a financial success, another change was in store.

In 2002 Kharas helped co-produce Animation Jam for UNICEF, shorts from 14 animators that talked about health, education and equitability issues from a children’s point of view. He saw how media opened youth to behaviour change and how animation could be used across cultural boundaries. It could transcend politics.

And this was the goal when he sat down with Johannesburg film maker Brent Quinn to figure out a way to stem the world’s largest epidemic of HIV/AIDS that South Africa’s government was trying to ignore: in 2003 alone, 150 AIDS-related deaths a day of children under five and two million “AIDS orphans.”

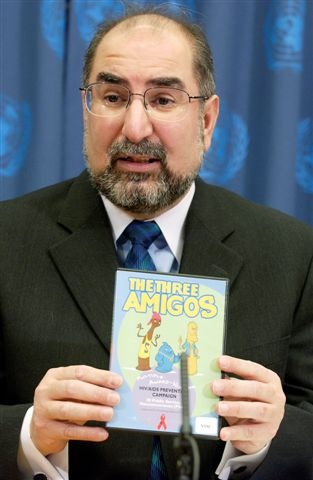

What emerged from their collaboration was about youth, humour and three animated-condom friends named Shaft, Stretch and Dick. By 2004 Kharas and Quinn had turned The Three Amigos into 20 short PSAs that stressed the value of condoms in the battle against AIDS. They had only two goals: to change behaviour and to save the lives of as many children as possible.

The series was officially launched to confused reporters in the press room at the United Nations’ headquarters in 2005: latex characters telling jokes about sex was well outside the organization’s usual box.

Within a year it was the world’s best-known condom campaign on TV and had earned Kharas a George Foster Peabody Award, the staunch advocacy of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu and death threats from Christian fundamentalists in the United States goaded by a critical Russ Limbaugh radio broadcast.

The campaign was produced completely by volunteers and supplied free of charge to any broadcaster around the world. By 2012 it had been translated into 47 languages and broadcast in 150 countries with a potential audience of 5.5-billion people, the only time condoms had been shown on Iran and North Korean television.

In 2008 Kharas produced a another non-profit PSA series called HYPERLINK Buzz and Bite, 30 animated spots to help combat malaria, and in 2011 he went after one of the world’s sacred cows – cultural justification for violence against women and children.

No Excuses uses 11 animated spots to reframe definitions of domestic violence, and again reporters at the UN launch were left wondering why this sensitive subject was being addressed by humour, sarcasm and characters of uncertain origin. Kharas felt it was the best way to bridge cultural and religious divides.

It’s why he calls himself a social entrepreneur rather than a media producer. “You have to understand that each individual is their own culture. This kind of idea, this innovation, is to get people talking, to change their frame of reference,” he says.

His non-profit work has continued with a pair of documentaries: A Child Without a Country: Pedro (2012), about a young Angolan boy caught for eight years in Canada’s refugee system, and No Thanks, We’re Fine (2011), about support for caregivers for those with dementia. He’s currently partnering with Nokero to create PSAs aimed at replacing kerosene and other unhealthy fuels with low-cost, solar-powered light bulbs.

Recent for-profit work has also focussed on progressive education: Magic Cellar (2006), the first African series about local culture for children; and Nan and Lili (2009), the first series for pre-school Arabic children.

It’s ironic that Firdaus Kharas is a household name in most of the developing world yet remains virtually unknown in Canada, unable to find funding for future projects that address international problems. His story will get a broader view when Gatineau’s Chispa Productions finishes its documentary called The Animated Activist that focusses on No Excuses. No broadcast date has been set yet.

Mike Levin has been a working journalist for 35 years covering the environment, business, culture and the music industry for daily newspapers and magazines in Canada, the United States, Europe and Asia. Now living in Ottawa he focusses on the arts and on creative people who fly under Canada’s mainstream cultural radar.