In the third and final story in a series on prisoner rights and labour, rabble.ca looks at some of the barriers people face finding employment, and what can be done to help them secure work.

Mark Kerwin couldn’t stop raving about his morning coffee, even as he watched it spill out of the coffee pot, spread across the counter and drip on to the floor. He was rushed; a light rainfall in the early December morning made his commute from Newmarket to Toronto’s East End longer than usual — not how he hoped a day of meetings would start.

Kerwin works long hours for little pay as the executive director of Klink Coffee, a coffee distributor in Toronto’s Greek Town, a job he calls the best he’s ever had. He has been with the company since August 2016. He loves the product, roasted by Reunion Island Coffee, a fair-trade, organic coffee roaster in Oakville, Ont. Klink purchases the coffee and sells it to businesses and individuals across Canada.

“I haven’t had anyone say, ‘I don’t love this coffee,'” Kerwin said. On a recent trip to Morocco, he found himself longing for a cup.

Business is growing. The company has made the most it ever has in recent months. But on average, it only brings in about $5,000 monthly. It needs a lot more — mainly to cover wages for staff. They’re the real reason Kerwin loves his job, and the coffee, so much.

Training individuals previously involved in the criminal justice system

Klink is a social enterprise run by the John Howard Society of Toronto. It hires people who have recently been released from jail, or who struggle to find work because of their criminal records. The goal is for more than half of the employees be people with criminal records. Not everyone who works there has a criminal record; Kerwin doesn’t.

Klink made about $50,000 last year; Kerwin wants that to climb to $250,000 by April 2019, when the organization’s funding from the Toronto Enterprise Fund, a fund that supports social enterprises across the city, expires.

Originally, Klink was set up to offer short-term employment and job training for people leaving the criminal justice system. People came to Klink for a week to learn job skills. Then, they would be placed with other businesses for 11 weeks. Since opening in 2013, more than 50 people have completed the program.

Coffee is an “easy entry product,” Kerwin said. A lot is involved in selling it: grinding beans, making labels, processing orders, delivering products, sales, marketing and promotions. The goal is to give people real-world experience so they can be competitive in a rapidly changing job market, a job market they’ve been absent from while incarcerated.

“The last thing I want to do is get people leaving here with outdated skills who can’t be hired in the marketplace,” Kerwin said.

The model’s changed a bit over the years. Now, some employees stay at Klink for much longer than 12 weeks. This increases the costs. Klink pays employees $15 an hour. The organization receives funding for part of employees’ salaries during the first 12 weeks they’re with Klink. After that, Klink pays it all. Most of the revenue goes toward salaries.

But the biggest challenge isn’t increasing sales. It’s finding people who will hire Klink’s employees after their time at the coffee company ends.

Decades of “tough-on-crime” rhetoric has made many employers fearful to hire people with criminal records, Kerwin said.

“It’s not easy,” he said. “It’s not sick kids. It’s not pandas.”

Gainful employment has been shown to be one of the main factors to guarantee successful reintegration after release from incarceration. Finding work can be hard. There are practical considerations. Conditions may restrict where people can work. Kerwin can’t send someone to deliver coffee to a school who isn’t allowed to be near one.

But the intangible barrier — the stigma a criminal record creates — is something both potential employees, and employers need to overcome.

Overcoming discrimination in hiring

Kate Collins has helped people in British Columbia find work after release for more than 20 years. She’s seen attitudes change during this time. Years ago, she would bang on doors to convince employers to hire her clients. Often, businesses didn’t want to talk to her.

It was “ignorance, in the true sense of the word,” she said. Employers had no idea what working with people who’ve been incarcerated would be like. Now, they often contact her asking for her to find them workers. She’s had employers go from hesitating to hire her clients to requesting multiple workers in a matter of days.

Collins is quick to praise these employers. Yet, they declined to be interviewed about this practice, wanting to protect both the employees and the business.

They’re not the only ones.

Earlier this year, the Poverty Roundtable of Hastings Prince Edward in Ontario surveyed local employers about how they used criminal records in their hiring practices. Employers who hired people with criminal records were reluctant to state this publically, for fear it could harm business.

This shows how much work needs to be done to change people’s perception of people with criminal records, said Christine Durant, director of the poverty roundtable.

“People have served time; they’re done,” she said. “They’ve paid their punishment. So why are we as society continuing to punish people?”

There are legitimate reasons why employers may not want to speak publically about hiring people who have criminal records. It’s not just about protecting their business interests. Fellow employees may make the workplace uncomfortable for the colleague who has the criminal record. Collins said sometimes people have had to change jobs because of the work environment.

“There’s just a stigma attached to it,” said Marcia Nozick, CEO of EMBERS. The award-winning social enterprise in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside runs a temporary staffing agency that mainly places workers in construction jobs. All the people who come to EMBERS are in a transition that makes it hard for them to find work. Some are new to Canada, others have left drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs. Many have criminal records.

EMBERS hires workers, screens them and places them at appropriate job sites. Sometimes, workers from EMBERS are hired full-time by the companies where the agency places them. But Nozick remembers a business that cancelled its account with EMBERS when they find out an employee has a criminal record.

“People are not necessarily that forgiving,” said Nozick.

The best way to solve the problem, she said, may be for people with criminal records to tell their stories.

Stories help. Kerwin said people are often willing to buy coffee from Klink once they learn more about what the company does. The company’s “sweet spot” has been selling coffee to other social enterprises. One of his goals is to have Klink served in every John Howard society in Canada, and then potentially be used to raise funds for the organization.

He doesn’t think people only need one second chance. “I believe in millions of second chances,” he said. “I think we all get many chances every day, if we’re honest and humble. We all make mistakes on a regular basis.”

It’s not always easy. Some former Klink employees have re-offended.

Klink’s had failures, too. The coffee shop it used to run in Toronto’s West End had to close due to lack of funding. Kerwin wants to improve the online ordering process, and he’s constantly looking for volunteers who can sell the coffee at markets on the weekends. The more orders they get, the more people Kerwin can hire to fill them. Klink shares space with other John Howard Society of Toronto employees, and things get cramped.

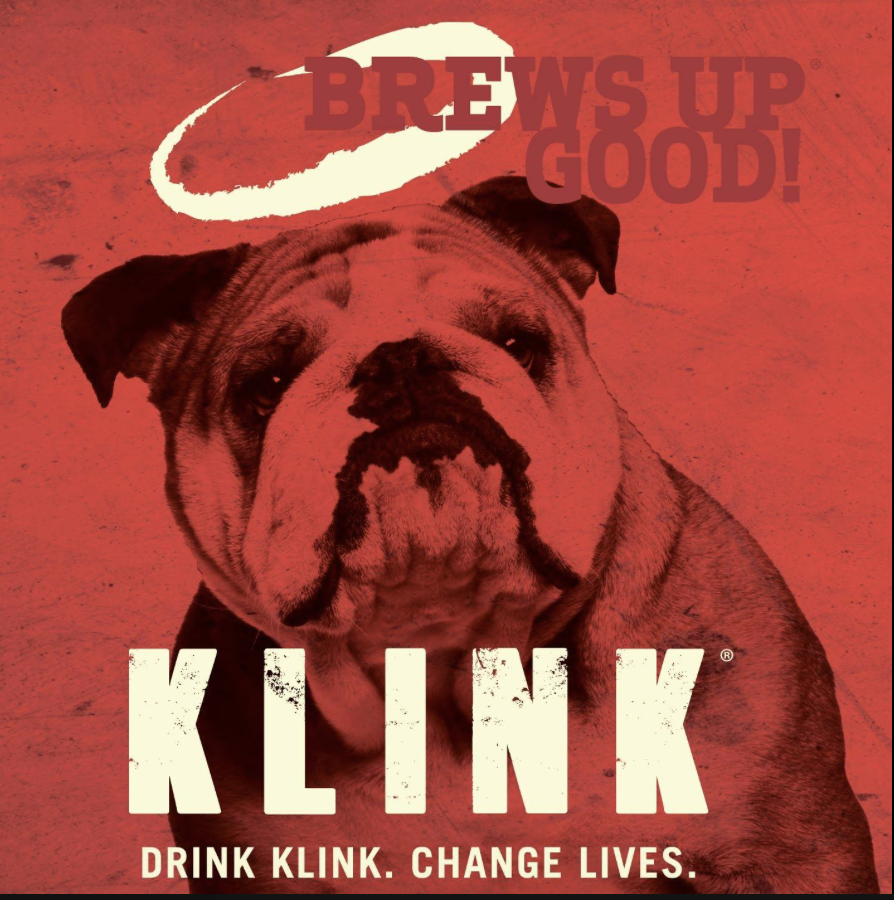

But for inspiration, he only needs to look at the company’s logo: a bulldog with a halo.

“It’s a dog with a heart of gold, that looks a little rough on the exterior,” he said. “British bulldogs are also known for standing their ground in the face of adversity, being stubborn, which represents us. Our mission in social justice. It’s really difficult. It’s hard to advance the cause, but we need to do it.”

Meagan Gillmore is rabble.ca‘s labour reporter.

Photo: Facebook.com/klinkcoffeecanada

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism.