Parliamentary reporter Karl Nerenberg opens 2018 with a special historical series, which looks forward to the coming year in politics by looking back. In this collection of articles, we travel back through 50 years of history, one decade at a time. Read the full series, spanning 1968-2018, here.

Half a century ago, in 1968, “revolution” was the word of the year. Advertisers peddled soft drinks and soap by labelling them as symbols of revolution. Even the Beatles felt compelled to do a song called Revolution.

Last year, when the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts put on an exhibition of art and artefacts of the late 1960s they called it, simply, Revolution. There were lots of bell-bottoms and psychedelic colours. Throngs of baby boomers flocked to the show to indulge in nostalgia, not politics.

The appeal of revolution, especially to those who exploited it for profit, was ephemeral and passing, like most pop culture fads. However, in 1968 there were also genuine, grass-roots uprisings around the world. If, in hindsight, 1968 was not really a year of revolutions, at least not successful ones, it was a year of resistance and rebellion.

The U.S. Democratic convention; a pig for president

In Chicago, demonstrators of many political hues gathered at the scene of the Democratic National Convention. Their primary purpose was to protest the war in Vietnam, which U.S. president Lyndon Johnson had been pursuing in an increasingly manic and unrestrained fashion.

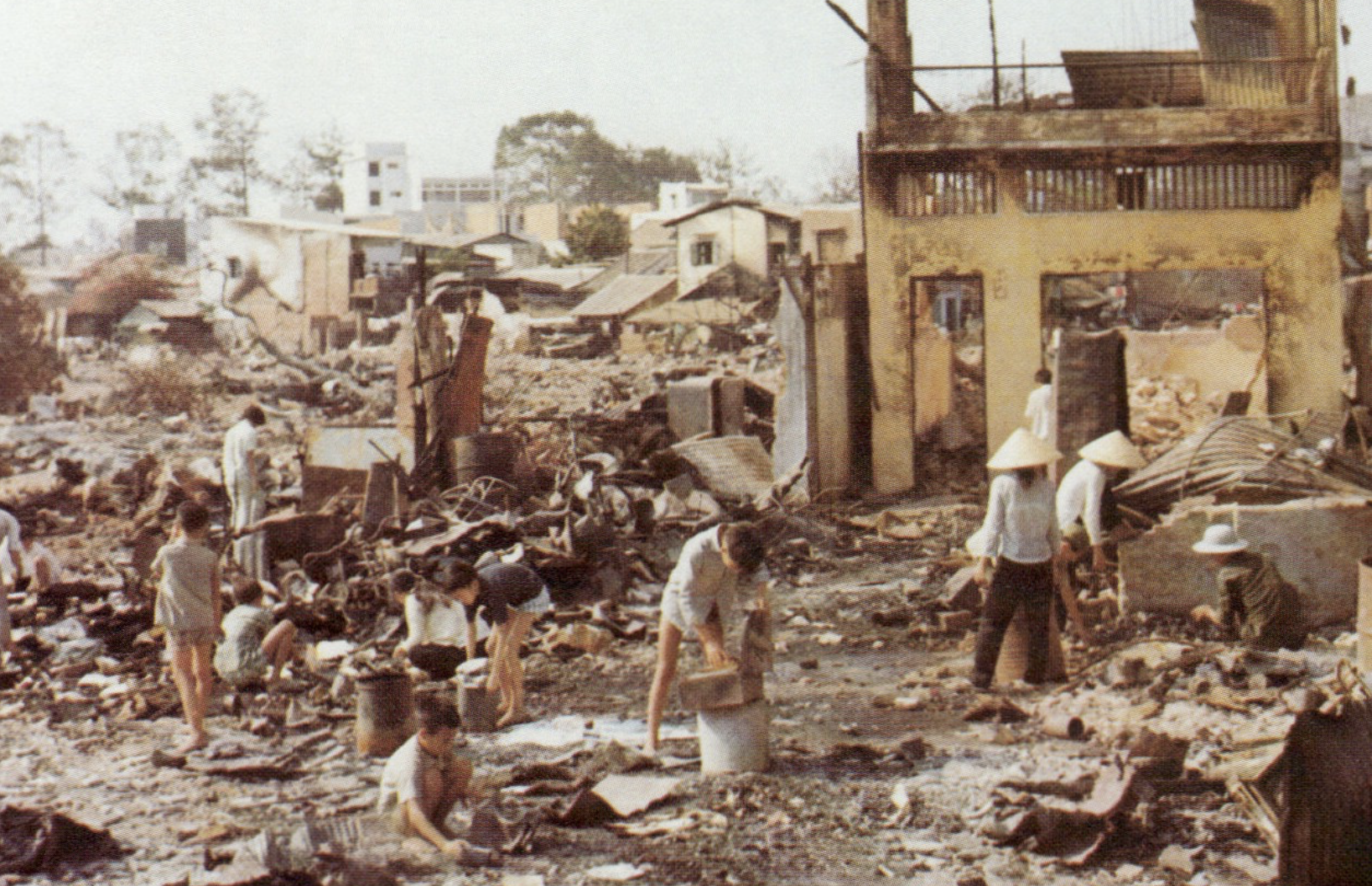

U.S. military tactics in Vietnam (and later Cambodia) included carpet-bombings and the burning of villages. The 1968 Chicago protests took many forms, with one group nominating a pig for president. The police reacted with brutal, almost gleeful, violence. They used truncheons and teargas and did not differentiate much between demonstrators and passers-by.

The convention of 1968 nominated Johnson’s vice president Hubert Humphrey, but it split the Democratic party between a reform/anti-war wing and a hawkish party establishment that included most trade unions.

It was a year of political melodrama. By the time of the Democratic convention, both Robert Kennedy, then a United States senator from New York and challenger for the Democratic nomination, and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Earlier in the year, arch-segregationist and former Alabama governor George Wallace launched his third-party candidacy for the presidency. His platform advocated continued second-class status for African Americans and harsh treatment for so-called communists and longhaired young protesters.

In the 1968 U.S. election Wallace won 13.5 per cent of the popular vote and the electoral votes of five southern states. The Wallace campaign appealed to many blue-collar voters in the north, ominously foreshadowing Donald Trump’s success in 2016.

The fractured political environment of 1968 ushered in the election of Republican Richard Nixon, who took heed of Wallace’s success with traditional (white) Democratic voters. He actively pursued a southern and white working-class strategy for his party, which had once been the elite, country club party. Nixon said he was for the “silent majority” of folks who were patriotic, hard-working, God fearing and did not march in the streets.

Nixon’s strategy has informed the continued, and too often successful, efforts of the American right to lure working-class Americans into voting against their interests by appealing to racism, jingoism and intolerant religiosity.

On the radical left, the Democratic convention resulted in major and very open splits as well. In 1969, a year after Chicago, the large umbrella youth radical group, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), dissolved into factions, including Maoist Progressive Labor and the Weather Underground, which unequivocally advocated violence against capitalist and state institutions. The Weathermen took their name from a line in a Bob Dylan song – “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows” – and they immediately became an object of intense scrutiny by the FBI and other security forces.

Over the subsequent years, most of the Weather Underground leaders were arrested, although few served long sentences, and almost all returned to mainstream professional and political lives. Two of them, Bill Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn, married, became respected academics in Chicago, and were, famously, early supports of an obscure state politician by the name of Barack Obama.

One of the original Weathermen, John Jacobs (J.J.), stayed underground. He fled to Canada and lived under an assumed name until his early death from cancer at the age of 50. Before J.J. decided to flee, three members of the faction of which he was part died in an explosion in a New York city townhouse. It had been caused by a blast from dynamite two of them were using to build a bomb.

And so, while after 1968 the left, to a large extent, disintegrated, the right turned in a populist direction and built a new base of support among blue-collar workers.

The Prague Spring

At the beginning of 1968, the reformer Alexander Dubcek became first secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and set about instituting a program of “socialism with a human face”. His reforms included decentralizing government and removing restrictions on freedom of speech and expression. Within months the Soviet Union and several of its Warsaw Pact allies invaded. The massive peaceful protests in the streets that ensued were no match for a military force of more than half a million troops.

It would be a generation before liberalization would come to Czechoslovakia and other eastern European countries. Today, we see that the democratization of the 1980s and 1990s has opened the doors to racist treatment of the Roma minority, widespread rejection of migrants and refugees from the developing world, and the rapid rise of nationalist and populist forces of the right.

The Tlatelolco Massacre

Mexico hosted the summer Olympics in 1968, the first Latin American country to do so. Ten days before that event, students staged a demonstration to protest the authoritarian and anti-worker polices of the governing Institutional Revolutionary Party, the PRI.

About 10,000 people gathered peacefully to listen to speeches in a large public square in the Tlatelolco district of the capital. Some chanted: “we don’t want Olympics; we want revolution.” The authorities’ reaction was brutal and bloody. They attacked the protesters from the air, by helicopter, and from the ground and nearby buildings, with live ammunition. Their tactics included snipers and machine guns. Hundreds were killed, and more than a thousand arrested. Many bystanders were shot, including Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci. Soldiers shot her three times, then dragged her body into a basement to leave her for dead.

Despite the bloodshed, the Olympics took place in Mexico City, as planned, and the PRI candidate went on to win the next presidential election in 1970. PRI candidates won every subsequent Mexican election, save one, in 2000, when Vicente Fox of the neo-liberal National Action Party (PAN) won.

May in Paris

The events of the month of May 1968 in France have acquired near legendary status. Veterans of that conflict call themselves soixante-huitards (sixty-eighters) and wear the label with pride. The uprisings in France were far more broadly based than in the U.S. or elsewhere and had significant consequences, both short and long term. They started in the Paris suburb of Nanterre. A small group of students and activists occupied a university building demanding more equitable access to higher education. The protests then spread to the Sorbonne on Paris’ left bank and throughout the country.

Workers joined with the students and community activists, almost spontaneously. At one point in May 1968, 11 million French workers were on wildcat strikes or were occupying their factories. The program of the uprising, to the extent there was one, had expanded from demands for reforms in higher education to an attack on the class structure of French society and on the power and influence of U.S. imperialism.

French President Charles de Gaulle was forced to flee the country and his government seemed paralysed. For a moment it looked like France was on the verge of another revolution. Members of the upper classes were actually arming themselves to prepare for the coming battle.

But the revolution did not happen. The then-strong Communist Party refused to take extra-legal action to overthrow the government, sticking to its belief that it should achieve state power only through the ballot box. The myriad of other May 1968 groups and groupuscles lacked anything resembling a coherent plan. And, in counter reaction, hundreds of thousands of government supporters had taken to the streets. De Gaulle regained control. He did so, in part, by calling a snap election for June. His party and its allies went on to win that vote with an increased majority.

Still, the uprisings of May 1968 marked the beginning of the end for the French president. Despite his and his allied parties’ electoral victory, de Gaulle remained unpopular. The World War II leader of the Free French, who had notionally rescued France from the threat of a military/extreme-right coup in 1958, was now seen as an authoritarian and disconnected figure.

De Gaulle tried to re-fashion himself as a reformer. He held a constitutional referendum a year after the events of May 1968, which would have created a more decentralized form of government. But he failed. Shortly thereafter he resigned and retired to his country home.

Reverberations in Quebec

The events in France found their echo elsewhere, especially in Quebec, where there was an active student movement and where students took to the streets and occupied school buildings.

One of the Quebec protesters’ key demands was for increased access to higher education. Historically, post-secondary education in Quebec had been reserved for a small elite. The system was built on the private collège classiques, which excluded most poor and working-class youth. The large reform of the early 1960s, which saw the creation of public community colleges, the CEGEPs, went part way to opening educational opportunities for all. But it did not go far enough because it did not sufficiently expand the university system.

After massive student protests in the fall of 1968, significantly inspired by the French example, the Quebec government decided to create the public Université de Québec system, consisting of five, French language, public universities throughout the province. A sixth was added subsequently.

This reform, in the spirit of the times, was accomplished quickly, over a two-year period.

In the final instalment of this series, we will look at the early Pierre Trudeau era and the beginnings of an Indigenous peoples’ movement in Canada. Stay tuned.

Photo: United States Army Center of Military History/Wikipedia

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism.