A farming suburb north of Toronto seems like an unlikely place to start up a series of Indigenous programming, but the Whitchurch-Stouffville Public Library took up the call to action in 2018. The library wanted to engage its patrons with Indigenous content. It felt that non-Indigenous patrons had a crucial role to play in the reconciliation — and that the library was the ideal place for this to come about.

Whitchurch-Stouffville is located in the riding of Jane Philpott, former federal minister of Indigenous services. The new initiative had Philpott’s backing but was brought to life by library manager Shonna Froebel.

For Froebel — incorporating more Indigenous programming is personal. Her adopted brother, who is Indigenous, was part of the Sixties Scoop. In the mid-20th century, the Canadian government took Indigenous children from their families and placed them in foster homes or up for adoption.

Philpott was actively involved with the process, sending contacts and ideas to the library and how they might be helpful in incorporating reconciliation into the library sphere — such as the Blanket Exercise.

The Blanket Exercise was developed after the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996. An interactive experience, The Blanket Exercise walks participants through Indigenous rights through history — going from pre-contact with settlers, to treaties, to colonization, to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report. Participants walk on colourful blankets made to represent the land. They read prompts to help experience what First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples endured during colonization. Facilitators and Indigenous elders play the part of European settlers. Offered through the Whitchurch-Stouffville Public Library, library card holders participated in the Blanket Exercise for $10 for the session.

Just 25 people out of Whitchurch-Stouffville’s population of 45,837 identified as having Indigenous ancestry. Fifteen were First Nations, while 10 were Métis.

Despite the demographics, Froebel says circulation of materials by Indigenous authors — as well as the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission report — has been steady, meaning non-Indigenous residents are taking up an interest in the library’s Indigenous collection. Other events at the library’s Indigenous programming include presentations on the Williams Treaties — where Stouffville is situated, the Huron-Wendat — the people who lived there — and the history of residential schools.

“The library’s role in the community is kind of multifaceted but part of it is kind of informal education and offering those opportunities to learn,” she says. “Making that information available is really, really important so it’s easily accessible for people from all walks of life.”

Froebel says her staff looked to the University of Alberta’s “Indigenous Canada,” a massive open online course for inspiration, but wanted to localize the content to Whitchurch-Stouffville. Archaeological digs show that the municipality is now on the land previously occupied by the Huron-Wendat.

“One of the things with libraries is you can’t always look at what other libraries are doing because you have to be responsive to your community,” she says. “We don’t have any kind of reserve within our town limits or anything like that, but I want to look to topics that would be relevant.”

Whitchurch-Stouffville isn’t the only Greater Toronto Area suburb looking to engage non-Indigenous patrons with Indigenous materials and resources at the library. Last fall, the Mississauga Public Library ran a book club-type discussion with library patrons in the fall of 2018 to read sections of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, led by Cat Criger, the elder in residence at the University of Toronto.

Over the course of several months the book club met in a small room — next-door to the Open Window Hub — to discuss a different section of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report each week. Of the 12 attendees present at the book club’s second-last meeting, the majority were female, white and middle-aged, and expressed a keen interest in educating themselves about residential schools and intergenerational trauma. They read highlighted passages from their notes and articulated their surprise that Indigenous history wasn’t taught during their school years. Librarian Diana Krawczyk also sat in on the meetings, providing information on items in the library’s collection could further their understanding of one of the darkest chapters in Canadian history.

In 2017, the Toronto Public Library released a report on strategies for Indigenous initiatives as a response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action a few years earlier, listing 42 strategies for Indigenous initiatives like organizing an elder-in-residence program, or incorporating medicine gardens into future library landscaping. The library sought more supports such as recruitment and retention of Indigenous library staff members. The Toronto Public Library board endorsed the strategies on the condition that the library would engage with Indigenous communities and have those results presented back to them.

On Spadina Road — the street that got its name from the Ojibwe word for hill — a Toronto Public Library branch neighbours the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto and boasts a robust “Native Peoples collection.” The Spadina Road branch got its start in 1970 when staff and community members at the Native Centre approached the library to ask for a branch specifically designed for the Indigenous community.

Melanie Ribau, a library specialist in Indigenous community connections at the Toronto Public Library previously worked out of the Spadina Road branch. Now, she works at the Toronto Reference Library with Cynthia Toniolo, who manages adult services and program development at the Toronto Public Library.

Toniolo says that the Toronto Public Library is creating a place that is safe and welcoming for everyone — and that includes Indigenous communities.

“We seek ways to convey the message that our doors are open, our services are available and that you, too can find things here that are meaningful to you,” she says.

For non-Indigenous people — the settler community — she says education and awareness are key. Ribau says her goal is to make the settler community aware that their predetermined attitudes about Indigenous awareness could be harmful.

“It’s the people who make demands of their governments,” she says, hopeful that the public will ask more of their elected officials to include more Indigenous programs and services at the library and elsewhere.

The library has its own Indigenous advisory council — made up of Indigenous community members and representatives from Indigenous services agencies across Toronto to provide input on things like the Indigenous strategies that they felt were important to them, like the elder-in-residence program that ran in the fall of 2018. It also gave advice on the library’s “Read Indigenous” campaign, which includes hand-selected Indigenous book recommendations.

Through the first elder-in-residence program, anyone could contact the library to arrange face-to-face time with husband-and-wife elders Patrick Etherington and Frances Whiskeychan, who would answer questions or offer teachings to library patrons. Both Etherington and Whiskeychan are survivors of residential school.

Etherington is soft-spoken and chooses his words deliberately when talking about his inaugural role as elder in residence. He says the library branching out into Indigenous programs and teachings has been vital. There’s no word in the English language to describe how he feels, instead he uses the word “nanaskomin,” which he says roughly translates to “acknowledgement to all.”

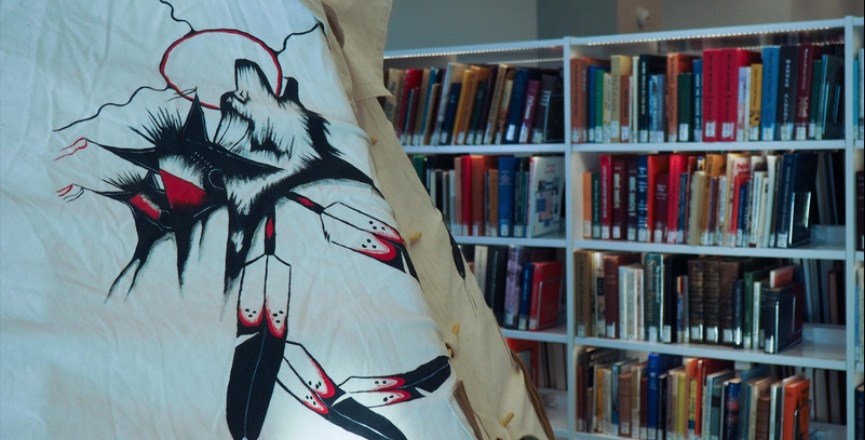

Although the elder-in-residence program ended last year, the library is looking at other ways to respond to its Indigenous patrons. In a survey last fall about a renovation for a library in Toronto’s east-end, many respondents asked if it could be a place where smudging could be permitted in the buildings. They also wanted to see more Indigenous artwork and designs in the library.

“We realize that we’re a pretty mainstream institution — about as colonial as you could possibly get,” says Toniolo. She says the library has its blind spots — but employees must take responsibility to further their education to make the library more accessible to Indigenous peoples.

“We need to start at a certain level of knowledge and awareness. We’re not asking them [Indigenous peoples] to spell everything out for us,” Ribau says.

Toniolo agrees — the library has “to do the heavy lifting.” While the increased Indigenous components in the Toronto Public Library have been well-received, Toniolo said they got “a few questioning emails” from people about the validity of the library’s land acknowledgment from a legal standpoint. There are some critics of the land acknowledgement practice who argue that land acknowledgements could open up a complicated legal situation that would allow for some First Nations to affirm legal rights to the land.

“We don’t expect everyone to agree but those statements are important to us. And we did it for a reason. We worked with community members in developing them and we stand behind them,” she says.

Toronto’s 100 library branches extend from as far east as the Humberwood branch near Pearson International Airport and as far west as the Port Union branch near the Toronto Zoo in Scarborough. Because of the geographic sprawl of the library system, the Toronto Public Library has three different land acknowledgement statements, written in consultation with the Indigenous advisory council. The library also has a general statement posted on its website.

“I don’t think I would still be in this position if it wasn’t personal. That’s what keeps me here,” says Ribau. “I have been kept awake at night oftentimes thinking about some of the challenges that we face. There’s a lot of self-doubt in there as well. Is this the right direction to go in? Are we doing the right thing?”

For Desmond Wong, who works out of the University of Toronto libraries, there is a difference between tangible steps to include reconciliation in the library space and those who do it as an afterthought. When librarians fail to consult with Indigenous community members, he says, it’s a failing of librarianship.

“I think it’s a check mark,” says Wong of libraries trying to justify reconciliation without that relationship-building. “That’s not what reconciliation is. It’s not a checkmark.”

Other southern Ontario libraries are naming spaces after local Indigenous history to varying levels of community engagement.

In 2017, the Markham Public Library opened its Aaniin branch. “Aaniin” means “hello” or “welcome” in Ojibwe — chosen to coincide with Canada’s sesquicentennial celebrations and according to its site, “in honour of our First Nations people” without mentioning any specific relationship between First Nations people and the City of Markham. However, earlier that year the city signed a “Cultural Collaboration with Eabametoong First Nation,” to promote “harmony and goodwill for the betterment of their residents” as well as collaboration socially, culturally and economically.

In Barrie, Ontario, the downtown branch recently underwent a renaming ceremony for one of its spaces — now known as the Enji-Maawnjiding Gathering Place. The space was renamed on April 4, and commemorated with a drumming ceremony with the Barrie Native Friendship Centre. The Georgian Bay Métis Council was also present to commemorate the renaming of the new space in the library.

To move forward with reconciliation in the library space, Wong says more Indigenous librarians are needed at higher levels within the system to create spaces for the revitalization and renaissance of Indigenous cultures. This is, in large part, because libraries have played a part in the erasure and the destruction of Indigenous identities.

Even with regular items in Toronto Public Library’s collection, it can be easy to assess whether an item is valuable to the collection based on how many times it’s circulated, or for events, how many people have attended programs to justify the cost. Ribau says this quantifiable way of tracking the items isn’t necessarily the best case for Indigenous titles — despite that there’s a flourishing literary scene of Indigenous writers — many of which have long waitlists.

“In some cases when it comes to Indigenous content for our collections, we can’t use the number of times it’s circulated because we should have that stuff there whether or not it’s circulated,” says Ribau.

The Toronto Public Library says there have been complaints about subject headings, classifications and cataloguing, but it’s bound to the wider authority of Library of Congress and the American Library Association. Now, there’s a push in the library community towards revamping the Dewey Decimal system in favour of call numbers that would better reflect items in the Indigenous collection. For example, some books about specific Indigenous cultures and traditions may still be categorized under 201 — the Dewey Decimal System classification for general mythology.

Even if those who have had a negative experience in the library space, Wong says that libraries have an indescribable quality of bringing people back.

“If I get burned by an iron, I’m going to be far less willing to touch it thereafter. That doesn’t seem to be the case with the library.”

Last week: Part 4 of rabble’s series: “Decolonizing the Public Library“

Next week: Part 6 of rabble’s series: The Future of the Public Library.

Olivia Robinson is a writer, journalist and book publishing professional. She is rabble.ca‘s Jack Layton Journalism for Change Fellow in 2019.

Image: Olivia robinson/rabble