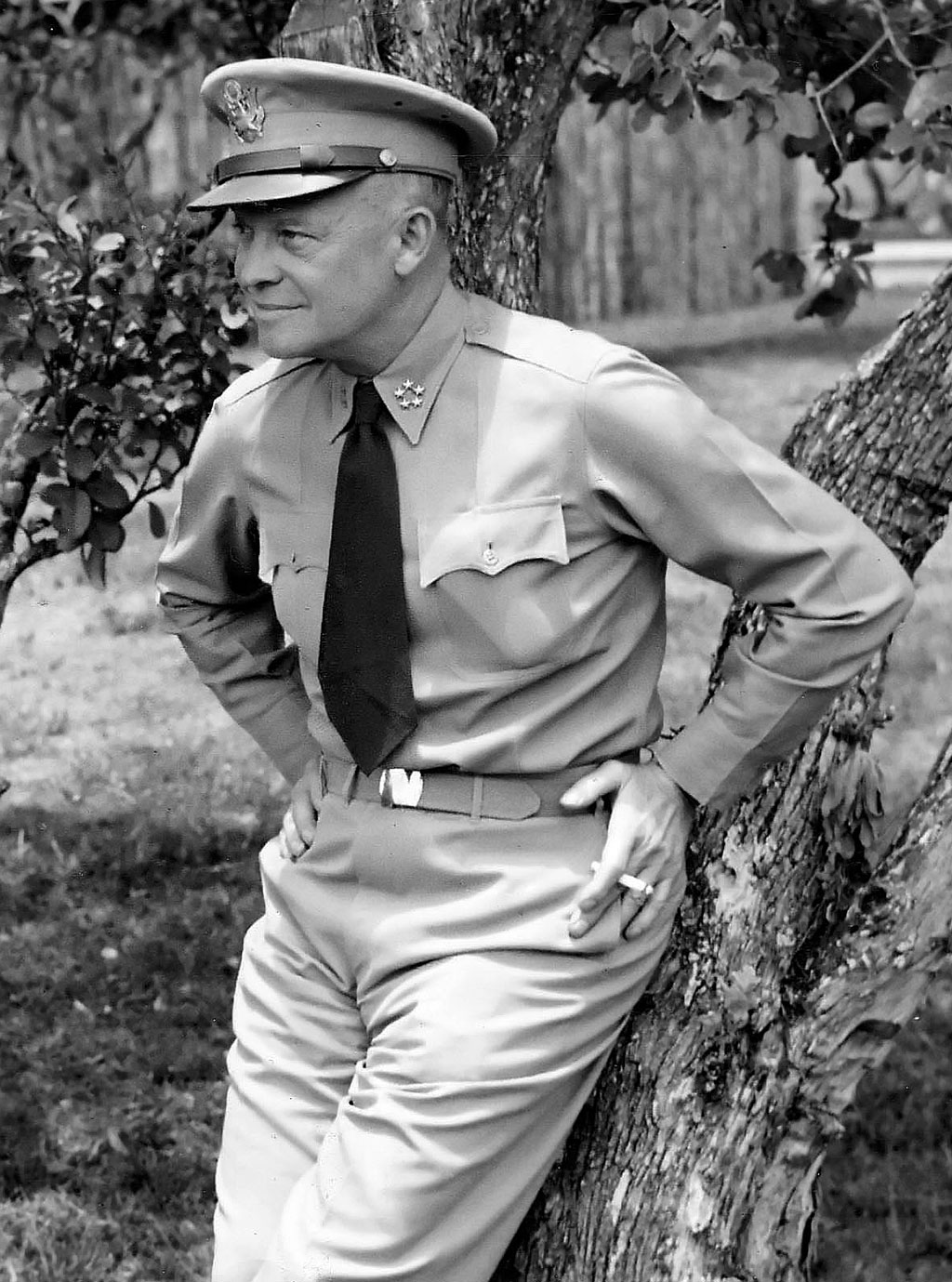

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and not clothed. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children.” — Dwight D. Eisenhower, April 16, 1953

Canadian Chief of Defence Staff General Walter Natynczyk is hot to trot, ready and eager for new military missions. He’s telling his troops to keep their “kit packed up” ready for new military adventures: “We have some men and women who have had two, three and four tours and what they’re telling me is ‘Sir, we’ve got that bumper sticker. Can we go somewhere else now?’ You also have the young sailors, soldiers, airmen and women who have just finished basic training and they want to go somewhere and in their minds it was going to be Afghanistan. So if not Afghanistan, where’s it going to be?”

Supplying the ideological framework for Natynczyk’s military operational perspective is Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s militaristic vision of Canada’s mission. Harper, who believes that the “courageous warrior” is a founding principle of Canadian identity, told MacLeans, “Canada has a proud military history, beginning with the War of 1812 that essentially began to establish our sense of national identity. The real defining moments for the country [are] where you take a side and show you can contribute to the right side. We have to be prepared to contribute more, and that is what this government’s been doing.”

Military Adventurism

Author Yves Engler has argued that Prime Minister Stephen Harper is preparing Canada to be in a constant state of war readiness. And, indeed, on any objective grounds it seems clear that the Harper Conservatives intend on taking Canada into a new phase of aggressive militarization. The purchase of four giant C-17 Globemaster military transport planes; the government’s stubborn insistence on purchasing 65 F-35 stealth fighter jets at a cost of $25 billion and counting; the $35 billion National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS) awarded to Halifax and Vancouver shipyards to build 21 combat and 7 non-combat vessels; recent agreements the Harper Government has concluded for military bases in Germany, Jamaica, and Kuwait and negotiations for others in Kenya, Senegal, Singapore, South Korea, and Tanzania; the ongoing military training mission in Afghanistan (950 personnel are posted there) after over a decade of military operations; Canada’s recent involvement in the NATO military campaign in Libya; and the Conservative Government’s $28 million campaign to glorify the Canadian involvement in the War of 1812 (in point of fact Canada did not exist in 1812 so the military campaign actually involved British forces).

It’s a colossal escapade in military adventurism by a country historically better known for its many contributions to United Nations peacekeeping missions, and for former Prime Minister Lester Pearson’s Nobel Peace Prize for his role in defusing the Suez Canal Crisis. Is this really where we want to go as a nation?

It’s a colossal escapade in military adventurism by a country historically better known for its many contributions to United Nations peacekeeping missions, and for former Prime Minister Lester Pearson’s Nobel Peace Prize for his role in defusing the Suez Canal Crisis. Is this really where we want to go as a nation?

In 2011 Canada’s military budget was $21.2 billion, 1.4 per cent of the country’s GDP and the 14th largest in the world. It pales in comparison with our neighbour to the south, by far the most profligate military spender in the world, who shelled out $687.1 billion in 2011, 4.7 per cent of the country’s GDP. Furthermore, the military-industrial complex in the USA, annually sells upwards of $12.2 billion of weapons, 34.8 per cent of the world’s trade in arms. Nevertheless, despite the fact that absolute American spending is 32.4 times that of Canadian expenditures, per capita American spending of $2,141 USD is only 3.8 times that of Canadian at $560 USD per capita, a clear indication that Canada is shoveling a substantial amount of money into the gaping military maw. Although the Harper Government is promising to cut $1.1 billion in spending from the military’s budget by the 2014-2015 fiscal year (a 5.2 per cent decrease), it’s difficult to ascertain if this means anything substantive, since purchases such as F-35 fighter jets and combat vessels are not planned to show up in the government’s books until 2016 and 2018 at the earliest.

Seduction Starts Here

Nevertheless, such military spending is proving irresistibly attractive to Canadian provincial governments. Both Nova Scotia’s NDP government, and British Columbia’s Liberal government, fell all over themselves in paroxysms of joy at winning shipbuilding contracts (Halifax’s Irving Shipbuilding will be building the 21 combat vessels; Vancouver’s Seaspan Marine the 7 Coast Guard vessels). In Nova Scotia it even lead to the patently pointless Ships Start Here campaign [pointless since the process of awarding the contracts was entirely merit-based, with sloganeering and hucksterism not factored into the equation at all] — a transparent attempt by the Nova Scotia government to siphon credit for the deal into its own political coffers.

Nevertheless, such military spending is proving irresistibly attractive to Canadian provincial governments. Both Nova Scotia’s NDP government, and British Columbia’s Liberal government, fell all over themselves in paroxysms of joy at winning shipbuilding contracts (Halifax’s Irving Shipbuilding will be building the 21 combat vessels; Vancouver’s Seaspan Marine the 7 Coast Guard vessels). In Nova Scotia it even lead to the patently pointless Ships Start Here campaign [pointless since the process of awarding the contracts was entirely merit-based, with sloganeering and hucksterism not factored into the equation at all] — a transparent attempt by the Nova Scotia government to siphon credit for the deal into its own political coffers.

There’s no doubt, of course, that such construction programs will generate employment and substantial spin-off (including corporate profits). Dangle such luscious carrots in front of cash-starved provincial governments and they will salivate like a leaky Enbridge pipeline. Of course, the perpetually un-asked question in such contexts is, what comparative economic impact (jobs, economic spin-off, technological, social, and environmental dividends, etc.) could $35 billion spent otherwise (say, invested in developing renewable energy) have? It’s a shortsighted political calculus that takes as self-evident that such military spending is indispensable and thus inevitable.

Nonetheless, the situation isn’t entirely black and white (for reasons discussed below) and a satisfactory resolution to this issue provides a substantial challenge for Canadian progressives, given how deeply embedded military culture is in Canada, and the realities of the global stage. For these reasons I propose … military subversion.

Military Subversion

In Canada the ministry is called the Department of National Defence (DND), and not of Offence, and certainly not of War. Supposing we take this seriously, and not in the Orwellian sense of the Harper Conservatives [Statistics Canada shorn of its capacity to collect statistics; the Department of the Environment doing it’s utmost to compromise environmental integrity; the Department of Agriculture overseeing the destruction of the Canadian Wheat Board; the Department of Immigration providing obstacles to immigration and demonizing refugees; the Department of Finance doing its level best to deprive the government of finances through never-ending tax cuts]. Supposing that the Department of National Defence could be directed to defending — Canada’s citizens, its environment, its natural resources, and the social, ethical, moral, and political values of its people. There is a plethora of ways — some variable currently recognized and supported, others not at all — in which the skills, abilities, training, and resources of a Department of National Defence could serve important and constructive objectives.

This is, then, a covert program to subvert by stealth — fossilized thinking, belligerent posturing, wasteful spending, and macho chest-pounding — and replace it with something better and more productive.

1. International Humanitarian Assistance

Vividly in the minds of many Canadians is the role that the military was able to play in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake that devastated large areas in the south of the country, killing an estimated 316,000 people, injuring over 300,000, and leaving homeless over a million. Such disasters are beyond the capacity of any country to deal with, let alone an impoverished state such as Haiti. Searching for and rescuing survivors, providing medical care for the injured, supplying food, housing, and clean water, clearing rubble, rebuilding damaged infrastructure — these are all tasks that an energetic, skilled, well-trained, and well-resourced group like the military can and should undertake. Equipping and training our military to do this allows Canada to make a tangible contribution in relieving suffering and rebuilding nations.

Vividly in the minds of many Canadians is the role that the military was able to play in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake that devastated large areas in the south of the country, killing an estimated 316,000 people, injuring over 300,000, and leaving homeless over a million. Such disasters are beyond the capacity of any country to deal with, let alone an impoverished state such as Haiti. Searching for and rescuing survivors, providing medical care for the injured, supplying food, housing, and clean water, clearing rubble, rebuilding damaged infrastructure — these are all tasks that an energetic, skilled, well-trained, and well-resourced group like the military can and should undertake. Equipping and training our military to do this allows Canada to make a tangible contribution in relieving suffering and rebuilding nations.

2. Coastal Patrols

Canada has already had vivid experience in human, drugs, weapons, and other contraband smuggling. The Coast Guard and the RCMP have roles to play in intercepting and stopping such activities, but the skills, capacities, and technology of the military can make significant contributions to such efforts.

3. Fisheries Patrols

Canada has an enormous coastline, some 243,000 kilometers, by far the longest in the world. As such, its territorial waters cover some 7.1 million square kilometers — equivalent to about 70 per cent of its land mass. Canada is responsible a huge swath of the ocean, preserving its ecological integrity and safeguarding its fisheries resources. Canada has already experienced illegal fisheries, and with the ocean being ruthlessly exploited and fish stocks being depleted, it is reasonable to suppose that such attempts at exploiting closed areas, using illegal fishing gear, unlawfully harvesting protected stocks, and other exploitation will continue. The Coast Guard plays a role here, but with a national fleet of 26 large vessels, 33 small vessels, 22 helicopters, and 45 lifeboats, and 7.1 million square kilometers to cover and a multitude of tasks on its plate, its capacity is clearly limited. The military’s skills, capacities, and technology could make a valuable contribution.

Canada has an enormous coastline, some 243,000 kilometers, by far the longest in the world. As such, its territorial waters cover some 7.1 million square kilometers — equivalent to about 70 per cent of its land mass. Canada is responsible a huge swath of the ocean, preserving its ecological integrity and safeguarding its fisheries resources. Canada has already experienced illegal fisheries, and with the ocean being ruthlessly exploited and fish stocks being depleted, it is reasonable to suppose that such attempts at exploiting closed areas, using illegal fishing gear, unlawfully harvesting protected stocks, and other exploitation will continue. The Coast Guard plays a role here, but with a national fleet of 26 large vessels, 33 small vessels, 22 helicopters, and 45 lifeboats, and 7.1 million square kilometers to cover and a multitude of tasks on its plate, its capacity is clearly limited. The military’s skills, capacities, and technology could make a valuable contribution.

4. Search and Rescue

Ditto. The Canadian Coast Guard takes a point position on search and rescue, but with its role in installing and servicing navigation aids, surveying navigation channels, conducting hydrographic missions, escorting vessels through ice, assisting with the management of commercial ship movements, and dealing with pollution events, they have their hands full. Furthermore, budget cuts by the Harper Conservatives have lead to the loss of some 763 Coast Guard positions, part of the federal government’s plan to cut the Department of Fisheries and Ocean’s (DFO) operational budget by $79.3 million. Sinking ships, fishers in distress, air crashes — the military’s skills, capacities, and technology can help avert or mitigate disaster and human suffering.

Ditto. The Canadian Coast Guard takes a point position on search and rescue, but with its role in installing and servicing navigation aids, surveying navigation channels, conducting hydrographic missions, escorting vessels through ice, assisting with the management of commercial ship movements, and dealing with pollution events, they have their hands full. Furthermore, budget cuts by the Harper Conservatives have lead to the loss of some 763 Coast Guard positions, part of the federal government’s plan to cut the Department of Fisheries and Ocean’s (DFO) operational budget by $79.3 million. Sinking ships, fishers in distress, air crashes — the military’s skills, capacities, and technology can help avert or mitigate disaster and human suffering.

5. Arctic Patrol

Ditto. Are the Russians or the Americans sending nuclear submarines through the Canadian Arctic? What about pollution events or oil spills in remote arctic regions? Who can find these? Who can respond?

6. Domestic Disaster Relief

Earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, mudslides, avalanches, hurricanes, tornados, ice storms … Canada has had recent experience with all of these. With extreme weather events dramatically on the rise as a result of climate change, such potentially disastrous situations are certain to become more, rather than less, frequent. Finding victims, helping the injured, evacuating the wounded and vulnerable, clearing wreckage and debris, filling sandbags, shoring up dikes … it’s important to have a rapid-response capacity to do all of the above. It’s an opportunity for talented, skilled, well-trained, and energetic people to help their fellow citizens in distress.

Earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, mudslides, avalanches, hurricanes, tornados, ice storms … Canada has had recent experience with all of these. With extreme weather events dramatically on the rise as a result of climate change, such potentially disastrous situations are certain to become more, rather than less, frequent. Finding victims, helping the injured, evacuating the wounded and vulnerable, clearing wreckage and debris, filling sandbags, shoring up dikes … it’s important to have a rapid-response capacity to do all of the above. It’s an opportunity for talented, skilled, well-trained, and energetic people to help their fellow citizens in distress.

7. Scientific Research

When I started oceanographic research in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, the Bedford Institute of Oceanography was arguably the third most active and prestigious oceanographic research institute in the world (after Woods Hole and Scripps in the USA). As a result of successive government cutbacks it’s now a pale shadow of its former self. Where once there were four major oceanographic research vessels (and more contracted on an annual basis) there is now one. Many research groups are financially unable to mount any field- research. Canadian capacity to understand and monitor our own oceans has been reduced to the skeletal.

This urgently needs to be reversed, but one low-cost way in which more basic oceanographic, physiographic, and meteorological data could be gathered is in the course of military missions. Side-scan sonar to record bathymetry; ongoing measurements of salinity, temperature, chlorophyll, nutrients, and current flow; ozone, methane, and carbon dioxide measurements; meteorological observations, sightings of whales. DND personnel can’t be expected to become scientists, designing experiments, analyzing, data, writing publications — but they can be trained to be scientific technicians: operating equipment and gathering and logging data. Canada could take advantage of opportunities to collect and share important oceanographic, meteorological, and ecological information.

8. Pollution

From oil spills to floating garbage, many hazards afflict Canada’s waters and shorelines. The March 2011 tsunami that hit Japan is estimated to have cast some 4.8 million tones of debris into the Pacific. This vast field of debris is being propelled by wind and currents across the Pacific Ocean. Some items have already started washing ashore in British Columbia, and oceanographers calculate that the main debris field will reach North American shores sometime between March 2013 and March 2014. How much may wash ashore is an open question with some scientists estimating that 95 per cent may remain in a North Pacific “garbage” gyre. This debris poses significant hazards to both navigation and to sea-life. Canada could make a significant contribution to navigational safety and the ecological integrity of the oceans and shorelines by mounting a major military mission to track this garbage, coordinate the gathering and disposal of washed-ashore debris, and investigate methods or removing or otherwise remediating the risks of the material that remains at sea.

From oil spills to floating garbage, many hazards afflict Canada’s waters and shorelines. The March 2011 tsunami that hit Japan is estimated to have cast some 4.8 million tones of debris into the Pacific. This vast field of debris is being propelled by wind and currents across the Pacific Ocean. Some items have already started washing ashore in British Columbia, and oceanographers calculate that the main debris field will reach North American shores sometime between March 2013 and March 2014. How much may wash ashore is an open question with some scientists estimating that 95 per cent may remain in a North Pacific “garbage” gyre. This debris poses significant hazards to both navigation and to sea-life. Canada could make a significant contribution to navigational safety and the ecological integrity of the oceans and shorelines by mounting a major military mission to track this garbage, coordinate the gathering and disposal of washed-ashore debris, and investigate methods or removing or otherwise remediating the risks of the material that remains at sea.

9. Peace-keeping, peace-making, and genocide-prevention

Bosnia, Kosovo, Rwanda, Libya, South Sudan, Syria … all these places and many others now carry sinister overtones. Who can forget the July 1995 massacre of over 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys in the town of Srebrenica, while the world and the United Nations Protection Force of 400 Dutch peacekeepers stood by on the sidelines? Who can forget the genocidal murder of over 800,000 Rwandans (Tutsis and pro-peace Hutus) while the world vacillated?

Bestial forces exist in the world and responding to these in the context of multi-lateral missions is the sharp and dangerous end of a controversial stick. There is little doubt that had NATO coalition forces not intervened on March 19, 2011 in Benghazi, a wholesale massacre of Libyan people would have taken place by loyalist forces of Muammar Gaddafi, already then entering the western and southern precincts of the city.

In helpless horror the world watches the daily atrocities perpetrated by the regime of Syrian strongman Bashar Assad on the citizens of his country, United Nations action paralyzed for months by the indifference and self-interest of the Russians and Chinese who have blocked action by the Security Council. The Russians are major arms suppliers to the Syrian regime and have a vital military base in Tartus in Syria, their last remaining military base outside the territory of the former Soviet Union and its only Mediterranean fuel depot. There is little doubt that such shortsighted mercenary objectives drive Russian intransigence.

Canada has long played a prominent role in global peace-keeping operations: in the Suez (1965-1967), Congo (1960-1964 & 1999-), Indonesia (1962-1963), Cyprus (1964-), Israel and Syria (1974-), Lebanon (1978), Sinai (1981-), Namibia (1989-1990), Western Sahara (1991-1994), Cambodia (1992-1993), Somalia (1992), Croatia (1992-1995), Haiti (1993-2000 & 2004), Rwanda (1993-1996), Central African Republic (1998-2000), East Timor (1999-2002), Kosovo (1999-2002), Sierra Leone (1999-2005), Ethiopia and Eritrea (2000), Sudan (2005-), and Darfur (2009-). Canada has taken part in 33 United Nations (UN) peacekeeping missions. Once considered a major player in the development of peacekeeping (following Lester Pearson’s role in the Suez Canal crisis) Canada’s role has diminished in the past two decades. For example, in 2006 Canada ranked 51st in its contribution of UN peacekeepers with only 130 members amongst the total UN deployment of over 70,000.

Canada has long played a prominent role in global peace-keeping operations: in the Suez (1965-1967), Congo (1960-1964 & 1999-), Indonesia (1962-1963), Cyprus (1964-), Israel and Syria (1974-), Lebanon (1978), Sinai (1981-), Namibia (1989-1990), Western Sahara (1991-1994), Cambodia (1992-1993), Somalia (1992), Croatia (1992-1995), Haiti (1993-2000 & 2004), Rwanda (1993-1996), Central African Republic (1998-2000), East Timor (1999-2002), Kosovo (1999-2002), Sierra Leone (1999-2005), Ethiopia and Eritrea (2000), Sudan (2005-), and Darfur (2009-). Canada has taken part in 33 United Nations (UN) peacekeeping missions. Once considered a major player in the development of peacekeeping (following Lester Pearson’s role in the Suez Canal crisis) Canada’s role has diminished in the past two decades. For example, in 2006 Canada ranked 51st in its contribution of UN peacekeepers with only 130 members amongst the total UN deployment of over 70,000.

There are those who argue that the path to peace involves abolishing the military altogether, and that there is no justification for the application of force. It’s a principled, ideological position, and I respect the intentions of those who advocate for pacifism. As an operational principle it fails to grapple with the challenges posed by despots like Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Radko Mladic, Radovan Karadzic, Muammar Gaddafi, and Bashar Assad who without hesitation embark on campaigns of mass murder for ideological reasons, or for simple greed and avarice. In such situations the choices we are presented with are not between war and peace, but between something bad and something very much worse. Consequently, it is important that Canada not wash its hands of peacekeeping, peace-making, and genocide-prevention challenges.

Military Transformation

These are only some illustrations of what useful roles the military could play in Canada and in supporting Canadian humanitarian and environmental values abroad. The overall objective of such subversion being the transformation of the military culture to one that fully embraces defence — environmental, social, ethical, moral, political, and humanitarian — and isn’t cast solely in the offensive, combative image of the traditional military.

These are only some illustrations of what useful roles the military could play in Canada and in supporting Canadian humanitarian and environmental values abroad. The overall objective of such subversion being the transformation of the military culture to one that fully embraces defence — environmental, social, ethical, moral, political, and humanitarian — and isn’t cast solely in the offensive, combative image of the traditional military.

None of this is truly subversive unless these transformative principles permeate the military and its political masters. Refocusing the military would require that all decisions from recruitment, equipment purchases, and training reflect these objectives. So, for example, the purchase of F-35 stealth, first-strike, battlefield jet fighters — virtually useless for any other purpose — would immediately drop off the radar. Aside from the grotesque and ballooning costs, aircraft such as these would simply have no place in a military focused on defence. Every other equipment and training decision would have to be viewed through the lens of how it would — or would not — serve a military with a different set of objectives.

Objections

It can be argued that some of the points outlined above can be as well or even better served by directly increasing funding to the Canadian Coast Guard, to scientific research through DFO, or via other mechanisms. This is an entirely valid point that I have no objection to. How to transition from a society with an embedded traditional military culture towards a different value-set is what is principally at issue. There may be more than one pathway to arrive at such a result: what’s important is that we set out in the right direction, and sooner rather than later.

Political Resolve

Of course, subverting the military involves political will. How do Canada’s political parties stack up in their determination to do so?

A. The Harper Conservatives: Dead in the water

It’s clear that the politics of Stephen Harper are moving — hell bent for leather — in precisely the opposite direction, towards aggressive militarization predicated on narrow “might-is-right” ideology. Defense Minister Peter McKay’s vision of guiding the military towards more civilian objectives would appear to be limited to the use of military aircraft to fly him from fishing lodges to lobster festivals.

B. The Green Party: Changing the frame

The Canadian Green Party has an extensive defence policy, really a lengthy concatenation of policies pertaining to a large number of specific and general situations. Its general principles include adherence to:

- Alternate conflict resolution, ecosystem protection, disaster relief, and strengthening of the UN;

- The international Green pillar of nonviolence, working for a culture of peace and cooperation between states, the rejection of militarism, and the commitment to economic and social development, environmental safety and respect for human rights;

- Multilateral disarmament, peaceful resolution of conflict, military conversion, support for United Nations peacekeeping operations, and the strengthening of the United Nations through reform of the Security Council and the expansion of the role of the General Assembly;

- Reviewing Canada’s membership in military alliances including NATO and NORAD and recommitment to its opposition to nuclear weapons, and a ban on the export of military equipment;

- The right of all countries to be free from military intervention by other countries except under the United Nations Responsibility to Protect doctrine.

There’s little doubt that if Canada were to espouse these principles, it would radically reframe the role of the military in the country. However, with only one Member of Parliament and the support of 9.5 per cent of Canadians, this seems unlikely as an immediate prospect.

C. The Liberal Party: Mixed signals

The Liberal Party of Canada has espoused a variety of policies. On the one had, under former Prime Minister Paul Martin, the Liberals refused to be drawn into a continental ballistic missile system with the United States. On the other hand, in 2001 under former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, Canada began a long entanglement in the war in Afghanistan, with complex and contradictory objectives and results. On military spending, former Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff vaguely intimated that the Liberals would not reverse anything, but would simply review future plans once a Liberal government took office. In their 2011 election platform “Red Book” the Liberals proposed that:

- Canada should remain in Afghanistan until 2014;

- Canada would work for a wider acceptance of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine in preventing and addressing conflict and mass-scale human rights abuse;

- Canada should increase its participation in United Nations peacekeeping operations;

- Military spending should be increased;

- The Liberals would cancel the sole-sourced F-35 contract and replace it with an open completion (which would include the F-35s);

- Savings from a scaled-back Afghanistan mission would be channeled towards international development assistance.

The military analysis website Ceasefire.ca categorized these as potentially “good, bad, or ugly” depending on one’s point of view and how one interpreted some of the deliberately vague language of the policy paper.

D. The New Democratic Party: Changing the focus

The New Democratic Party (NDP) has consistently supported Canada’s role as a peacekeeping nation and has consistently opposed the purchase of the F-35 stealth fighters. It has opposed cutbacks to the Canadian Coast Guard and has supported improvements to Canada’s search and rescue capacity. NDP leader Thomas Mulcair has promised to “fortify the ability of Canada’s armed forces to respond to crises and disasters.” The NDP’s 2011 election platform promised to maintain current levels of defence spending and affirmed that under an NDP government the Canadian Forces would be “properly staffed, equipped and trained to effectively address the full range of possible military operations.”

The NDP’s 2011 election platform established three priorities for the Canadian military that military analyst David Pratt notes are a significant departure from postwar Canadian defence policy, which hitherto has been based upon: a) the defence of Canada; b) the defence of North America with the United States; and c) contributions to international peace and security. In contrast, Jack Layton’s 2011 NDP policy identified the priorities as a) defending Canada; b) supporting peacekeeping and peacemaking; and c) assisting with natural disasters at home and abroad. This is a significant departure in two regards:

1. “Peacekeeping and peacemaking” represent a quite different approach from “promoting international peace and security.” The concept of combat is firmly embedded in the latter, whereas it lies on the extremity of the former. As Pratt writes, “With the exception of the Libyan bombing campaign, the NDP has shown a marked reluctance to commit the Canadian Forces to combat missions. Consequently, it is reasonable to believe that the party will be predisposed against any future combat missions.”

2. Secondly, astute readers may have noticed that continental obligations to the United States (and perhaps even to North American military structures such as NATO and NORAD) are conspicuously absent from the NDP platform, which instead focuses on domestic and international disaster relief as an important priority for the military. In contrast to previous Canadian administrations, the “joined-at-the-hip” conception of Canadian-American relations is conspicuous by its absence.

Parting Shots

With the exception of the jingoistic belligerence of the Harper Conservatives, the seeds of military transformation are present in the platforms of all other Canadian political parties. To varying degrees they all appear to understand that a different conception of the military in Canadian society is at least possible. Yet the corrosive effects of militaristic values, military spending, the blunt instrument of military force, and the merchants of death are hard to underestimate. It was former American President Dwight D. Eisenhower who first warned against the “military-industrial complex”, coining the term in his farewell address to the Nation on January 17, 1961:

“This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

“We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals so that security and liberty may prosper together.”

Five-star former army general that he was, Eisenhower recognized more clearly and presciently than most, what a dire threat militarism posed, not only to other countries, but also to the democratic foundations of the host nation itself. Faced with such imperatives — which have only increased since the time of Eisenhower — we need to insist that our political parties listen to Eisenhower’s message — and take action accordingly. If civil society doesn’t succeed in transforming the military, it may itself become subverted — into an appendage of the military-industrial complex.

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.