Police have killed 34 and injured 78 striking miners at a platinum mine in South Africa’s Marikana. The mine is owned by the Lonmin Plc, which has a 2011 total annual revenue of over $1.5 billion (sources here and here from Lonmin company accounts, used to calculate annual revenue. Revenues totaled $1.6 billion in 2010).

The strikers, meanwhile, are paid roughly $300 to $500 per month. Many live in shacks, and many of them come from the rural Eastern Cape province which sees over half of its migrant population living in what some call ‘informal settlements’. Shack dwellings are predominantly treated as undesirable by state authorities that have been known to mobilize police forces against them as well as attempt to raze entire communities with little to no warning.

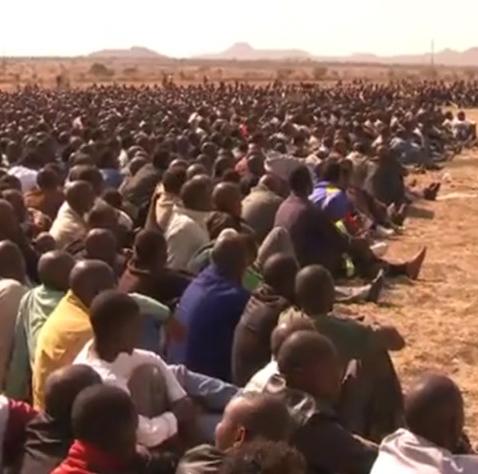

The strikers represent about 3,000 of the mine’s workers, all of them rock drill operators, a difficult and dangerous job. These rock drill operators were unilaterally offered a wage deal by Lonmin outside of the collective bargaining process, to which the affected workers responded by demanding higher wages. The workers’ demands were not met, after which they lay down their tools and occupied Nkaneng hill.

Lonmin’s platinum mines in South Africa make it the third largest producer in the world. The company is not new to resentment and resistance to its operations such as they are: they calculate for what they call “community unrest” and worker unrest in their public production reports as losses in profit and efficiency (from Lonmin Plc Fourth Quarter 2011 Production Report, found here). Under various iterations, the British firm has been doing business in the region since the time of apartheid.

Lonmin has threatened to fire all of the rock drill operators unless they return to work. In May 2011 they carried through a similar threat, firing over 9,000 workers at their Karee mine operation, prior to being asked to reapply and compete for the same jobs. Some workers claimed that they were intimidated by the union leadership of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) who supported the suspension of the workers’ branch leadership for disrespect, disobedience, for staying on past their appointed term of office, and for initiating “industrial action.” The same union has traditionally represented workers in the Marikana mine.

The rock drill operators delinked from NUM prior to the August 2012 strike and formed their own organization, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU). During the initial stages of the work stoppage, on the second weekend of August, there was violence between the AMCU workers on one side, and the NUM and police on the other, resulting in the death of 10 individuals across the board. The president and the general secretary of NUM have both said that they passed on the names of workers who they claim were violent to the police for action and that they requested steps be taken to enforce ‘security’ so that there would be a return to work. NUM’s deputy president said that “The people gathered on the mountain [Nkaneng hill] are suspects, but they are not searched, arrested or dispersed. What can a trade unionist do in such a situation?”

Some of the debate over the conditions and tensions in South Africa’s mines have led to calls for nationalization by certain members of the political elite. Ayanda Kota, spokesperson for the Unemployed People’s Movement, in response to the Marikana mine worker’s massacre, has refused to comply with the axis of national versus private ownership, calling instead for the following: “What we stand for is the socialisation, under workers’ control, of the mines. We also stand for reparations for the hundred years of exploitation.”

Such an outlook rejects to limit discussion and action to a narrow field of options that have often led to choosing between bad or worse conditions of life for the vast majority of those who work to generate the immense wealth predominantly enjoyed by a narrow band of select leaders in the dominant logic of private and public corporations.