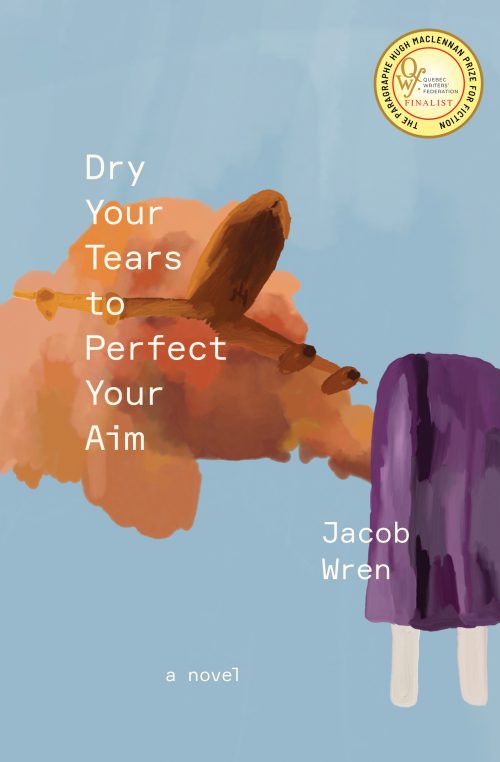

In Montreal author Jacob Wren’s new novel, Dry Your Tears to Perfect Your Aim, the protagonist is an earnestly neurotic and well-meaning writer from a First World country who travels to a fragile utopian liberated zone that is being bombed by his government. Some of his narrative is an account of what he experienced among the revolutionary activists he met there, especially the women fighters and organizers, and some is a pained reflection on whether it is legitimate for him to be among these militants. Is he a genuine ally, or an opportunistic tourist gathering up material for his next book? What are the responsibilities of a sympathetic visitor among a beleaguered population that suffers beneath bombs he indirectly funds through his taxes?

The American muckraker Lincoln Steffens famously said after visiting Russia during their revolution that “I have seen the future and it works.” Wren’s protagonist might represent an update on that assertion for the post-modern political pilgrim. – “I have seen the future and it is a disrupted, self-conscious narrative with an unreliable narrator who is more interested in his own inner life, such as it is, than in the revolution he came to support.”

The fictional liberated zone is largely based, according to the author, on Rojava, the three semi-independent Kurdish cantons of North Syria, and the political thought of Kurdish insurgent Abdullah Ocalan with other elements drawn from experiences of the Spanish revolution of the 1930s, the Nicaraguan Sandinistas and the Argentinian Neighborhood Assembly Movement of 2001-03. An explicit pro feminist commitment and focus on local autonomous organizing drawn from these historic models is reflected in life in the “thin strip of land” portrayed in Wren’s novel.

The protagonist spends time among the revolutionaries, sits in on committee meetings and popular assemblies, donates his never very competent labor to work projects in the liberated zone. He learns to shoot, although never very well, and is captured by the enemy on his first armed patrol. Held and tortured by the enemies of the revolution, the protagonist experiences all the Kafkaesque horrors of this period through the dulling lens of his depression. He returns home and tries to turn his experiences into literature, the book we are currently reading.

Wren’s protagonist is not the first visitor from safer, more privileged parts of the world to visit revolutions in progress, and to wrestle, with varying degrees of success, with the ethical puzzles that permeate this strange, somewhat difficult but in the end important work of fiction. Lord Byron and other Romantics travelled to the Greek revolution in the 1820s and American Transcendentalist author Margaret Fuller reported sympathetically on revolutionary struggles in Rome in 1849.

Lincoln Steffens was not the only America based radical who travelled to support the Russian revolution. Louise Bryant and John Reed also visited Russia during the revolution there and reported rapturously from the front lines. Emma Goldman, the great anarchist thinker and activist, was a pro-Bolshevik visitor at first, but realized sooner and more clearly than many other Western fans the profound flaws in democratic process that marred the Russian revolution and later turned the phrase “really existing socialism” into a bitter joke.

Later, Canadian icon Norman Bethune lent his medical skills to the Spanish Republic when it was attacked by fascists in the 1930s and later provided similarly useful help to Mao’s forces during the Chinese revolution. I am not aware of any of these earlier political pilgrims agonizing about personal authenticity or legitimacy in the way Wren’s protagonist does.

Still later, many Western sympathizers travelled to observe and participate in the Cuban revolution or to support the Sandinistas in Nicaragua or the Zapatistas in Mexico. A notable figure among these pilgrims was American feminist/ poet/activist Margaret Randall, who lived and worked in Cuba and Nicaragua for years and has written extensively about those experiences, including several books that critique these revolutions for their failure to fully integrate feminists perspectives, including Cuban Women Now: Interview with Cuban Women (1974), Sandino’s Daughters: Testimonies of Nicaraguan Women in Struggle (1981), Sandino’s Daughters Revisited: Feminism in Nicaragua (1994), and Gathering Rage: The Failure of 20th Century Revolutions to Develop a Feminist Agenda (1992). Randall may well be the figure among the crowds of political pilgrims the West has sent to foreign revolutions who has most successfully managed the inherent ethical dilemmas of the political pilgrim, the problems that so vex Wren’s unhappy protagonist.

None of this is to dismiss the real if modest literary success of Wren’s odd little novel. It is difficult to portray depression and torpor in ways that do not depress and immobilize the reader, and in large measure Wren pulls off that difficult task, while incorporating some of the currently popular themes of auto fiction. He is unlikely to find a large audience with this book, but some readers will find it fascinating, and use it as an invitation to tough reflection about their own political and literary work. Worth a look and some thoughtful examination.

For the Kurds from whom some inspiration for this novel was taken, they are once again facing adversity, but also opportunity, as the oppressive regime of Syrian dictator Bashar Al-Assad has begun disintegrating in recent weeks.