In Failing grades: The Canadian resource economy — Part 1 I embarked on an exploration of Canada’s resource economy. My motivation was the publication of The nine habits of highly effective resource economies: Lessons for Canada. Issued by the Canadian International Council (CIC) and written by Madeline Drohan, the Canadian correspondent for The Economist, it is a detailed inquiry into where Canada should go if we wish to make intelligent use of the natural assets with which our country is endowed.

The first important determinant of a wise resource economy strategy involves saving the windfall profits in sovereign wealth funds, not only to avoid the pitfalls of the “resource curse” and the attendant Dutch Disease it brings on its coattails, but also to build a multi-generational nest egg for the future when non-renewable resources run out. Salting away royalties in a stability fund can also insulate against the vicissitudes of commodity price fluctuations. On this measure, the policies of provincial governments and the Harper Conservatives clearly warrant a failing grade. In Part 2, I examine Habit # 2: Don’t stand still. Add, extract, and build value.

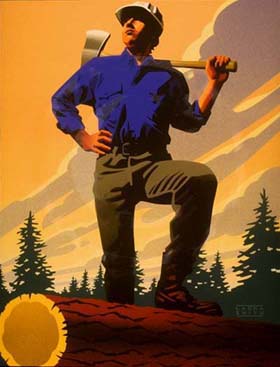

We return again to the “hewers of wood and drawers of water”. Natural resources are the sine qua non building blocks of any economy. Subsequent economic layers — manufacturing, processing, sales, service, professional, knowledge — all either add value to the base layer or exist in association with it. Wood must be hewn and water drawn, but they become useful economic entities when employed for larger purposes. Raw materials should be the starting point for an economic chain, not simply the endpoint

We return again to the “hewers of wood and drawers of water”. Natural resources are the sine qua non building blocks of any economy. Subsequent economic layers — manufacturing, processing, sales, service, professional, knowledge — all either add value to the base layer or exist in association with it. Wood must be hewn and water drawn, but they become useful economic entities when employed for larger purposes. Raw materials should be the starting point for an economic chain, not simply the endpoint

Adding value involves transforming raw materials (using forest products as an example) from raw logs to furniture, cabinetry, construction materials, paper, and musical instruments. In a more general sense, value can be added to forests by developing an understanding that they are more than pulp and lumber on the hoof, but managed sustainably can be the source of products like maple syrup, cork, nuts, pharmacological products, recreation, and tourism. Thus one can manage forests for reasons other than simply cutting them down.

Building value, in the sense used by the CIC report, involves developing technologies that are employed in all of the above activities, from harvesting machinery to forest mapping software. The training programs, whether through institutions or in a master-apprentice relationship, are also value built upon raw resources. Students (national and international) can attend institutions to learn skills, and master craftsmen can travel the world imparting their knowledge.

Extracting value ratchets technological development one notch higher through the creation of substances such as biofuels, nanocrsytalline cellulose, acetylated wood, and other high-tech products.

Similar value chains are constructed in relation to all other raw resource materials. Where these chains are not being built is Canada.

As one metric of this Drohan examines “technology exchange” [the sum of imports and exports of technology materials and services as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)]. Using technology exchange data compiled by the Conference Board of Canada from fifteen OECD nations, Canada sits at the bottom of the heap with a percentage of 0.3 per cent of GDP, a ranking that received a score of “D” from the Conference Board. Ireland, with a technology exchange of 27.6 per cent towers above other OECD countries, but even nations like Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Germany, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States have levels in the single digits, a degree of magnitude better than Canada.

In case you think that our poor performance on technology exchange might be an anomaly, think again. The Conference Board of Canada has graded the country on a large variety of measures having to do with innovation. It received on “B” for the number of scientific articles published (ranking 8th out of 17 peer OECD countries), two “C’s” for knowledge-intensive services (10th out of 17 OECD countries) and aerospace market share exports (a respectable 4th out of 17 OECD countries behind France, United States, and United Kingdom). In every other metric — nine of them — Canada received a “D”, trailing the pack or near the very bottom. And in case you think this is better than it is … the Conference Board allowed everyone to pass and didn’t assign any “F’s” on its report cards. Otherwise Canada would certainly have been sent to the dunce’s corner to repeat the semester

Although Research and Development (R&D) undertaken by Canadian universities is ranked very high — second only to that of Sweden — the transfer of this R&D into business is very low. Drohan quotes Dick DeStefano of the Sudbury Area Mining Supply and Service Association who told her, “If you look at Canadian mining, it has 0.2 per cent in R&D. If you look at mining suppliers, it’s something like 0.3 per cent. Compare that to any other industry in the world — plastics, pharmaceuticals — it’s 7, 8 and 9 per cent.”

The State of the Nation 2010: Canada’s Science, Technology and Innovation System report noted, “Research and development performed by business in Canada is low by international standards. Furthermore, from 2007 to 2009 Canadian industry R&D declined further in both current and real dollar terms.

Turning this around is a complex undertaking involving policies and initiatives from federal and provincial governments, but also from the private sector, corporations, financial establishments, and educational institutions. The salient point made in the CIC report is that “While it is business that turns a crisis into an opportunity, companies have difficulty doing so without access to an educated workforce, adequate infrastructure, and public research (emphasis added) — all within the purview of government.”

So what is the federal government doing in these areas that might benefit innovation and add value to the economy?

1. Education

The Canadian Federation of Students says the average debt for university graduates is almost $27,000 and nearly two million Canadians have student loans that total over $20 billion. The weight of this debt burden has the potential to impoverish an entire generation of young people, who not only have to repay these substantial sums, but are also doing so while paying interest rates of between 5 and 9 per cent. Canadian students pay on the order of $5.3 billion every year in tuition. Moreover, undergraduate, graduate, and college tuition rates have continued to increase at a rate greater than inflation (see An idiot’s persistence: Asinine adventures of the Harper Conservatives for further details).

2. Infrastructure

In a report to the Federation of Canadian Municipalities in 2009, Saeed Mirza and Cristian Sipos detailed a staggering infrastructure deficit and the urgent need for new infrastructure. Canada’s water, wastewater, transportation, transit, waste management, and cultural, social, and recreational facilities are greatly inadequate and aging. Twenty eight per cent are almost archaic at between 80 and 100 years old (well past their intended life of service), and a further 31 per cent are 40-80 years old (a total of 59 per cent). Much is in need of replacement, improvement, and maintenance.

In a report to the Federation of Canadian Municipalities in 2009, Saeed Mirza and Cristian Sipos detailed a staggering infrastructure deficit and the urgent need for new infrastructure. Canada’s water, wastewater, transportation, transit, waste management, and cultural, social, and recreational facilities are greatly inadequate and aging. Twenty eight per cent are almost archaic at between 80 and 100 years old (well past their intended life of service), and a further 31 per cent are 40-80 years old (a total of 59 per cent). Much is in need of replacement, improvement, and maintenance.

The Canadian government pledged $33 billion towards improving infrastructure, however Mirza, said, “That is a very small amount of money; $33 billion is totally inadequate…. Our politicians are forgetting our infrastructure deficit is really $400 billion. We need another $400 billion to upgrade on all levels and, unfortunately, our governments are not paying attention.” Mirza added that rather than focusing on legitimate needs, too much of the Building Canada fund has been spent on frivolous or trivial programs such as the construction of gazebos and lakes during the G-8 conference in Toronto in 2010. “The ministers” says Mirza “were shameless about it.”

3. Research

The Harper Government has presided over what is certainly the most systematic, concerted, and extensive attack on scientific research ever seen in Canada, indeed probably in the developed world. An editorial by Nature, one of the two most prestigious scientific publications in the world, detailed some of the most draconian recent cuts to science funding by the Harper Conservatives:

“The government plans to cut the Research Tools and Instruments Grants Program (RTI), the main equipment-funding scheme for basic researchers, and to jettison the 24-year-old National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (NRTEE), an independent source of expert advice to the government on sustainable economic growth.

“The government plans to cut the Research Tools and Instruments Grants Program (RTI), the main equipment-funding scheme for basic researchers, and to jettison the 24-year-old National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (NRTEE), an independent source of expert advice to the government on sustainable economic growth.

“It is hard to believe that finance is the true reason for these closures. Critics say that the government is targeting research into the natural environment because it does not like the results being produced. If the Harper government has valid strategic reasons to undermine vital sectors of Canadian science, then it should say so. If not, it should realize, and fast, that there is a difference between environmentalism and environmental science — and that the latter is an essential component of a national science programme, regardless of politics.”

The State of the Nation 2010 report praised the innovative work done by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), the Conservative Budget 2012 slashed funding for all of three of these key Canadian research funding institutions, a total of $60.3 million over three years, thereby pushing federal commitment to science, technology, and innovation in precisely the wrong direction. These funding cuts are in addition to funding cuts to Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Library and Archives Canada, the National Research Council Canada, and Statistics Canada — all organizations that could reasonably be supposed to support innovation in Canada.

In the CIC report Drohan draws attention to Smarter and Stronger: Taking Charge of Canada’s Energy Technology Future a report prepared by Tatiana Khanberg and Robert Joshi and published by the Mowat Centre. It makes a strong case that Canada needs a national energy strategy not only to supply raw resources but also to provide “the technology for the efficient development and use of energy across the entire energy system, the tools to reduce related environmental damage, and, eventually, the breakthrough technologies that will allow a transition to new sources of low-carbon energy.” In other words precisely the innovative approaches that add, build, and extract energy value and thereby pave the way a low- or no- carbon sustainable energy future.

In the CIC report Drohan draws attention to Smarter and Stronger: Taking Charge of Canada’s Energy Technology Future a report prepared by Tatiana Khanberg and Robert Joshi and published by the Mowat Centre. It makes a strong case that Canada needs a national energy strategy not only to supply raw resources but also to provide “the technology for the efficient development and use of energy across the entire energy system, the tools to reduce related environmental damage, and, eventually, the breakthrough technologies that will allow a transition to new sources of low-carbon energy.” In other words precisely the innovative approaches that add, build, and extract energy value and thereby pave the way a low- or no- carbon sustainable energy future.

Khanberg and Joshi argue further that:

“Energy technology should be the national energy priority. Becoming an energy technology leader should be a concrete policy commitment from both orders of government. That commitment should span the whole energy system, from supply to end-use. Canada’s current approach to energy technology investments is piecemeal and fragmented. These have a mediocre track record when assessed on the basis of measurable outputs, such as Canada’s (poor) performance in developing new energy technologies.

“A national energy strategy, with a sustained and comprehensive national approach to [energy] R&D as its foundation, is a precondition for energy superpower status. Development of a national energy strategy is of course a challenge, given provincial ownership of natural resources and a lack of alignment of regional interests on many energy issues.”

A striking illustration of how far we are from this objective was provided by this past summer’s Council of the Federation meetings in Halifax, Nova Scotia in July (see Canada’s energy future: Wise strategy or rapacious sellout?) While the provincial premiers (with the exception of British Columbia’s Christy Clark) committed to “assess the new challenges facing the energy sector and ensure that the country has a strategic, forward thinking approach for sustainable energy development that recognizes regional strengths and priorities and respects provincial, territorial and legislative jurisdiction over natural resources, a more integrated approach to climate change, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and managing the transition to a lower carbon economy” the federal government was AWOL with Stephen Harper refusing to even attend the meetings and discuss the issue.

Thus the “challenge” Khanberg and Joshi refer to may understate the case ensuring the continuation of a piecemeal and fragmented approach with mediocre (or worse) results.

Further underscoring this point is Framing the Future: Embracing the low-carbon economy published on October 18, 2012 by the soon-to-be-liquidated National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (NRTEE). It’s a strikingly thorough, well-researched, and visionary document that provides a blueprint for how Canada could become a world leader in the provision of low-carbon goods and services (LCGS), of which NRTEE writes:

Further underscoring this point is Framing the Future: Embracing the low-carbon economy published on October 18, 2012 by the soon-to-be-liquidated National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (NRTEE). It’s a strikingly thorough, well-researched, and visionary document that provides a blueprint for how Canada could become a world leader in the provision of low-carbon goods and services (LCGS), of which NRTEE writes:

“Annual global spending on LCGS is significant and growing quickly. Spending stood at roughly $339 billion in 2010. Our analysis shows that global spending could reach between $3.9 and $8.3 trillion by 2050, depending on climate policy assumptions. The growth potential in Canada is also notable. Taking into account existing and proposed climate policies, annual domestic spending on LCGS could rise from the $7.9 billion estimated for 2010 to $36 billion in 2050. Climate policies that cut emissions by 65 per cent from 2005 levels could drive domestic spending of roughly $60 billion in 2050. In either scenario for 2050, LCGS sectors grow more rapidly than the Canadian economy overall.”

This is the upside. There is a downside, however. If Canadian government thinking remains mired in inaction and (literally and figuratively) in fossilizing thinking about natural resources then:

“The economic risks of inaction are too significant to ignore. For one, billions of dollars in Canadian exports could be subject to trade measures that penalize emissions-intensive industries and products. For another, our international reputation could suffer and with it the marketability of Canadian products and the ability of Canadian firms to invest abroad. The cost of policy delay is also clear. Every year of delay in sending strong, economy-wide policy signals represents a wasted opportunity to take advantage of natural cycles of infrastructure and equipment renewal, making it more difficult and expensive to meet emissions reduction targets. Our analysis shows that waiting until 2020 to implement climate policy aimed at cutting emissions by 65 per cent from 2005 levels by 2050 implies close to $87 billion in refurbishments, retrofits and premature retirement of assets.”

The NRTEE report opens a farsighted vista on an environmentally sustainable vision of a low carbon world and Canada’s potential role in realizing such a future, a roadmap of how to get there, and a warning of the dangers of clinging to a non-renewable status quo. One fears that the impending dissolution of NTREE — created in 1988 under the Progressive Conservative administration of Brian Mulroney, and given its death sentence by the Harper Conservatives in the spring 2012 federal budget (NRTEE will cease operations in 2013) — may prove prophetic in regard to how seriously the federal government considers NRTEE’s proposals.

The NRTEE report opens a farsighted vista on an environmentally sustainable vision of a low carbon world and Canada’s potential role in realizing such a future, a roadmap of how to get there, and a warning of the dangers of clinging to a non-renewable status quo. One fears that the impending dissolution of NTREE — created in 1988 under the Progressive Conservative administration of Brian Mulroney, and given its death sentence by the Harper Conservatives in the spring 2012 federal budget (NRTEE will cease operations in 2013) — may prove prophetic in regard to how seriously the federal government considers NRTEE’s proposals.

In all these critical areas necessary to foster innovation that could add, build, and extract value from the natural resources sector, federal government policies have been running against the current of effective resource economies. While other nations are developing the advantages that natural resources convey, Canadian governments — federal and provincial — cruise the bland middle, if they are not actively paddling backwards. In a world of rapid social, technological, economic, political, and environmental change, not rocking this boat allows it to draw water — on a rapid course straight to Davy Jones’ Locker.

[Part 3 in this series Carbon attacks: The Harper Conservatives and the Canadian resource economy. Part 1 is Failing grades: The Canadian resource economy.]

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.