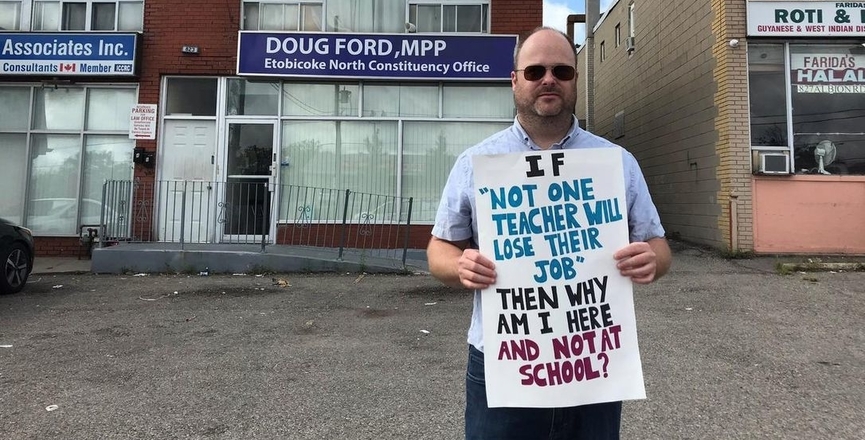

Jonathan LeFresne has been teaching for seven years. After four years of short- and long-term occasional work, LeFresne got a full-time contract in the 2018-2019 school year with the Toronto District School Board (TDSB). In spring 2019, Doug Ford’s government announced it was increasing class sizes, and LeFresne was declared surplus to the school, and later, the board. Despite assurances the TDSB would find a placement for him over the summer, on August 31 LeFresne was laid off.

Unemployed for the first week of September, LeFresne managed to pick up some short-term work in the second week. The TDSB then placed LeFresne in a long-term occasional position. Then, six weeks into the year, LeFresne was recalled to a 0.5 contract at a new school with three new classes created by reassigning students from a variety of established classes.

During all of this upheaval, LeFresne was completing his social sciences additional qualifications, at a personal cost of $725, in order to be more competitive in the recall process and LTO market.

LeFresne’s situation highlights the domino effect Ford’s cuts are having on students and teachers. In September, the TDSB laid off approximately 200 full-time teachers. They entered the long-term occasional pool which bumped an equivalent number of long-term teachers with less seniority into the daily supply pool where work is already scarce.

LeFresne’s contract ended January 30, 2020. On February 3 he started a long-term occasional position at a non-semestered school where he will be taking over six courses and working with 170 students.

Still, LeFresne remains cautious: “I am reasonably sure, barring sudden retirements or resignations, that I have been permanently reduced to a half-time contract from full-time. But again, nothing official on that. This also means, assuming I don’t get surplussed again next year, that I will likely be in two schools (or more) each year for the foreseeable future.”

Biology and chemistry teacher Sharie Sobers graduated from the two-year bachelor of education program at Queen’s University in 2016. She then took additional basic qualifications for intermediate and senior math to be more competitive in the high school job market.

Despite being a high school teacher, Sobers worked as a short-term elementary teacher with both the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board and TDSB in 2016-2017.

During the 2017-2018 school year she was called to the secondary panel. Sobers gained valuable experience and made it onto the long-term occasional list as well as the hire to contract list.

The decision paid off in the 2018-2019 school year when Sobers landed a one semester permanent contract that was increased to a full-year permanent contract. Sobers said she was “over the moon that I landed a position so quickly. There was a huge hiring that year due to the increase in enrollment and I felt fortunate to be in the midst of that.”

“Finally reaching what I thought was job security, I moved to Toronto and drastically cut down my commute. I was able to have benefits for the first time since graduating from university. I thought I had job security and wouldn’t have to interview anymore.”

Sobers’ happiness was short-lived. In March 2019, she was notified her position was potentially suplussed due to Ford’s education cuts. In August, Sobers was officially laid-off from the board.

Sobers said: “After Ford stripped me of my permanent status, I was a little shell-shocked. This year I’m back to occasional work covering a person who’s on sick leave first semester and a person on maternity leave for the second semester. Fortunate to be working, but it’s tough to feel like I’m back at square one.”

According to Paul Bocking, vice president and chief negotiator of the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation – Toronto (OSSTF-T) occasional teachers’ bargaining unit, “Over 120 permanent teachers remained surplussed this school year. Around half got some kind of fixed-term appoint for semester one. The rest returned to the occasional teacher’s list, some got long-term occasional work. For semester two, only around 30 of the 120 have positions lined up so far, so 90 are unplaced even for the semester. Those 120 teachers would teach over 700 classes over a year, were they fully employed.” This scenario is being played out across the province.

Students who can’t get courses they need to meet post secondary entrance requirements are forced to take night or summer classes — if there are spaces — or come back for a victory lap. That’s set to be the next income generator for the Ford government — charging students for additional credits.

Ministry spokesperson Ingrid Anderson said in a February 3 email, “As committed to in the spring, it is expected that there should be no involuntary job loss for teachers from the class size changes within the 2019-20 GSN. This was echoed by the independent Financial Accountability Officer, who confirmed that there would be sufficient funding to ensure no involuntary job loss due to the implementation of the class size changes.”

Daily occasional teachers are entry-level teachers who receive a set standard daily rate of pay and no benefits. Normally, they would eventually move into long-term occasional positions before being considered for a permanent contract. But that’s not happening any more.

According to Bocking: “The first several rounds of weekly LTO postings from mid-August to the end of September saw a decline of nearly 50 per cent compared to the same period in 2018. Week to week LTO postings since then have been similar in number.”

Supply teachers must work 10 consecutive days with the same kids teaching the same classes before their pay increases to reflect their qualifications and experience. That’s also the time they qualify for benefits which end with long-term placement.

As if that wasn’t enough, supply teachers are often disrespected and treated poorly by students. Students mistakenly see supply teachers as an excuse to opt out of completing assignments. Adding to the frustration is larger class sizes that make classroom management more challenging.

Unfortunately, not all full-time classroom teachers take this disruptive behaviour seriously, but Sobers makes sure her students treat supply teachers with respect. Sobers had her class write apology letters for being extremely loud and off-task with one supply teacher and made phone calls home to ensure that it wouldn’t happen again. Sobers put in the extra effort because, “I think part of the responsibility lies with the regular teacher to let the students know that respect is warranted regardless of if you’re with them for a day or for the entire semester.”

As Bocking points out, “Supply teaching is a usually invisible, thankless job. It’s very challenging, entering a new school every day or week and having to establish your reputation with students, as well as find out how to make photocopies and where the students are at in a unit plan. Supply teachers are generally given the least benefit of the doubt, should anything go wrong. But we’re certified teachers in our subject areas, who can do a lot more than babysit.”

Doreen Nicoll is a freelance writer, teacher, social activist and member of several community organizations working diligently to end poverty, hunger and gendered violence. A different version of this article appeared in NOW Toronto.

Image: Submitted

Editor’s note, February 3, 2020: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated LeFresne was placed in a long-term job in September last year. In fact, he was placed in a long-term occasional position. The original story also stated LeFresne began a new half-year contract on February 3. In fact, he started a long-term occasional position.