When Neela Devaki walks on stage and starts singing the song “Wanting,” it’s as though she’s speaking to an entire generation of Instagrammers who desire affirmation through likes and regrams.

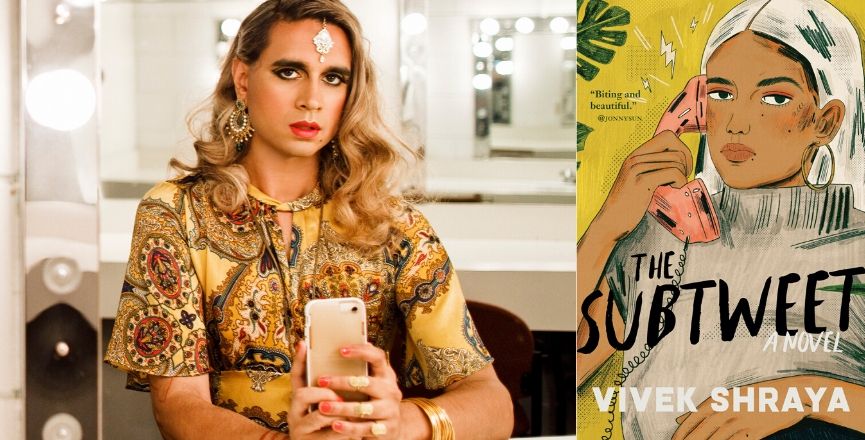

Except that these lyrics were written back in 2008, two years before the official launch of Instagram, the platform that plays a vital role in the budding friendship between Neela and Rukmini in Vivek Shraya’s The Subtweet. Her latest book follows last year’s graphic novel, Death Threat, in which Shraya revealed the darkest depths of internet culture and the dangers of easy online accessibility.

The Subtweet is similarly critical of how our URL presence can impact our IRL relationships. And yet, for a book ostensibly about online culture, The Subtweet also recognizes that our desire for affirmation existed long before social media came into our lives.

Set in 2018, The Subtweet follows the tumultuous but loving friendship between Neela and Rukmini, who bond over their shared affinities: they’re both musicians, brown women of colour, and Rukmini (who goes by the stylized RUK-MINI) became famous for covering Neela’s “Every Song.” The two meet at a music industry panel called “Race and Music,” with Neela as the moderator and Rukmini as a panelist.

This positioning sets the stage for one of the central conflicts in their relationship: Neela feels underappreciated and jealous of Rukmini’s rise to stardom; while Rukmini, who only sings covers, always worries that she’ll never be “an original” like Neela. In other words, they both want what the other has, but neither is able to admit it. Despite these tensions, the two become best friends.

Eventually, however, their inability to articulate their wantings leads to the downfall of their friendship. After Rukmini is asked to go on tour with white pop superstar Hayley Trace, Neela’s jealousy takes over and she posts the following subtweet: “Pandering to white people will get you everything #hegemony.” Neela’s first subtweet is quickly recognized as a jab at her best friend, with #hegemony referring to an album created by Rukmini a decade before with her now ex-friend Malika.

Included on the album was a bonus track entitled “Wanting,” which Rukmini sings on tour: “Nobody can see my isolation / Nobody can see how much I want to be friends / Nobody can see my wanting / Don’t want to be wanting / Because wanting is dangerous / Wanting is dangerous / I’ll suppress the beast, I’ll be my best for now.”

It would be easy to interpret these lyrics as Shraya’s critique of online culture and social media, which we’ve been told, time and time again, turns us all into narcissistic performers, constantly wanting more and more validation in the form of likes and follows.

But The Subtweet is not interested in such a critique. In fact, when we place these lyrics in the time in which they were written, we can see how this kind of “wanting” existed long before Instagram and Twitter became ingrained parts of our daily lives. The Subtweet demonstrates how one cannot “suppress the beast” of their wanting forever.

While social media can exacerbate our jealousy and longing, it is not the root cause of these feelings. After her subtweet goes viral, Neela acknowledges how the two friends have responded differently to “being brown women in a white world. You had questions and ideas and opinions. All I had were my regulations and reservations.” Neela’s lack of vulnerability is her survival strategy in a world ruled by the white cis-hetero-patriarchy. Social media illuminates the ways in which Neela’s “self-preservation” strategy isn’t actually serving her — at least not when it comes to her intimate relationships.

In a moment of vulnerability, Rukmini asks Neela why she never likes any of Rukmini’s photos on Instagram (a question that so, so many of us ask ourselves internally all the time). Neela then admits that, “I only like things I hate…If I like something, it feels kind of redundant and showy to declare it publicly…I just think that actually liking something is a private, internal feeling.” Eventually, Neela will have to confront the fact that her hate-liking policy extends into her IRL relationships as well.

In a letter to Rukmini, whom she hasn’t been able to get in touch with since her subtweet went viral, Neela explains: “I’m writing you this letter because I owe you more than an apology. I owe you an admission: I was jealous. Maybe if I had admitted this to myself sooner, I wouldn’t have reacted the way I did.” Neela’s jealousy has nothing to do with Rukmini’s success in music; rather, it’s Rukmini’s “effortlessness” and her ability to “thrive on building connections with other brown women…I was jealous of your ability to open up so freely to someone new, when it had taken me so long to open up to you.” Rukmini’s ability to be vulnerable, both on and off of social media, enables Neela to see that she can let go of her “reservations and regulations.”

At the end of her letter to Rukmini, Neela reveals how wanting isn’t the problem:

During the past few months, I have often looked for the green-eyed monster in the mirror and have been disappointed to see my own face. Seeing (and then hating) myself as a monster would be relatively easy. Instead, I am recognizing that the real monstrosity is not in wanting — even if it’s wanting what someone you love possesses — but in harbouring jealousy without naming it.

What Neela desires, what she wants but can’t name is embodied in the lyrics of “Wanting”: “Nobody can see my isolation / Nobody can see how much I want to be friends.” This is her own form of “self-preservation,” and while it may serve her as a brown woman “in a white world,” it isn’t serving her in her relationships with other brown women. And so, when she takes the stage as the new opener at Hayley Trace’s Toronto show, Neela’s choice to sing “Wanting,” a song that isn’t hers, but is hers at the same time, it becomes clear that she’s no longer interested in “harbouring jealousy without naming it.”

In Shraya’s The Subtweet the beast can no longer be repressed, and that’s a good thing. In offering this nuanced representation of desire and friendship, both IRL and URL, The Subtweet shows us that in a world that pathologizes vulnerability as weakness, we need now, more than ever, to let others see just how much we want to be friends.

Margeaux Feldman is a writer, educator and community-builder from Toronto and now living in Treaty 7 Territory in Calgary, Alberta. She’s currently completing her PhD in English literature and sexual diversity studies at the University of Toronto. Her writing has been published in PRISM, The Puritan, The Minola Review, GUTS Magazine, Shameless Magazine, and The Vault. She’s currently at work on a memoir entitled The Bed of Sickness: Essays on Care. You can learn more about her at margeauxfeldman.com

Author image: Vanessa Heins