Like this column? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

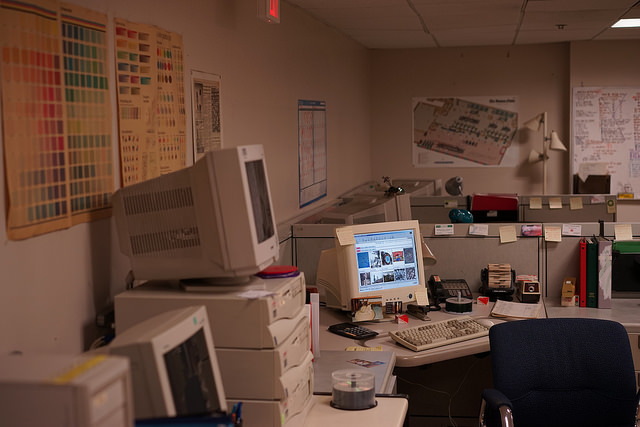

For anyone who’s worked in a newsroom for over a decade there’s a montage in the movie Spotlight that has to trigger a warm rush of nostalgia.

We see a newsroom library at the Boston Globe stuffed with clippings, file drawers and microfiche. Librarians, the saviours of journalists everywhere, rifle through old stories and print articles from spinning reels. They bundle the results into a brown file folder and deliver them to waiting reporters who already have teetering stacks on snack-strewn desks.

It’s July, 2001, a couple of months before the fall of the twin towers and a decade after the World Wide Web started being a phrase folks used at cocktail parties. In a later scene Sasha, the sole female reporter on the Spotlight team, is in church with her grandmother. Their priest is delivering a homily: “The other day I was on the World Wide Web. Anything you want to know. It’s right there. Now as a priest, I admit, this makes me a little nervous. Should I be worried about job security?”

We now know it was Sasha, not her priest, who should have been concerned. In 2001 the web was big enough to spark a sermon but not deep enough to replace the racks of clippings, the print directories and the microfilm the Spotlight team relied on for their investigation of pedophile priests and the system that allowed them to do so much damage in Boston and around the world.

And back then the web had already started picking at the financial heart of the newspaper business, want ads. In yet another scene, the paper’s new editor tells the head of the Spotlight team: “The Internet is cutting into the Classified business and I think I’m going to have to take a hard look at things.”

Today newspapers have taken that “hard look” as the Internet has, over the 15 years since the Spotlight team broke the priest story, cut into not only the Classified business, but display ads, ad value and circulation.

Today the kinds of resources the Spotlight team had — months to pick a story, even more to research and write one — is a distant fantasy. Many papers today, desperate for readership, are more interested in writing about Scandal than scandal. Or, as Margaret Sullivan, the New York Times public editor wrote last week about her paper’s failure to cover the water tragedy in Flint, Michigan:

“After all, enough Times firepower somehow has been found to document Hillary Clinton’s every sneeze, Donald Trump’s latest bombast, and Marco Rubio’s shiny boots. There seem to be plenty of Times resources for such hit-seeking missives as “breadfacing,” or for the Magazine’s thorough exploration of buffalo plaid and “lumbersexuals.” And staff was available to produce this week’s dare-you-not-to-click video on the rising social movement known as ‘Free the Nipple.'”

The spotlight is now falling in the wrong place. And the wheel has turned in the past 15 years. The web is hardly an upstart, though many papers act like the threat was born yesterday.

Postmedia, it seems, is on its deathbed, financial servicing American debtors and shrinking its local coverage. Torstar has given up on Guelph, Ontario, ceasing the publication of that city’s paper late last month. Journalism students are told to think like entrepreneurs, reporters are being asked to write drivel for advertisers, editors are thinking more like publishers, publishers are thinking more about head office than their own communities and head office cuts jobs, closes papers and services cross-border debt.

Meanwhile there are pedophiles, corporate criminals, bent cops and crooked politicians who know, just as the priest did at the beginning of Spotlight, that it has become easy to get away with it all.

Listen to an audio version of this column, read by the author, here.

Wayne MacPhail has been a print and online journalist for 25 years, and is a long-time writer for rabble.ca on technology and the Internet.

Photo: Tom Cole/flickr

Like this column? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.