Like this column? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Here’s a question: Can technology change the fundamental nature of story? I ask because a recent publishing experiment by Google suggests it can. I’m skeptical.

Stories have been around as long as human brains have been large enough to imagine the future. At first they were purely oral, told around a campfire, in dream song, epic poems, sung by scops in mead halls or captured in nursery rhymes. This was a time of story as a communal property and as a way of demonstrating the natural order, the nature of gods and the ways of the world. The stories were passed on, by word of mouth. The rhythm, rhyme and cadence of the words acting as an aide mémoire for the long, sometimes epic, tales of morality and battle.

Even when monks began to write down the works of Aquinas and others, the marginalia of one monk was often folded into the text when another monk did further transcription. The idea of authorship was mutable and collective. That’s also the case with the Talmud, perhaps the world’s first hypertext document, with rabbis commenting on rabbis commenting on rabbis in glosses that float around the edges of the main text.

When the book arrived on the scene in 1439, stories started to be the possession of authors. But the nature of the stories, narratives with heroes, villains, plots and resolutions, didn’t fundamentally change even though book technology went through massive shifts over the next 100 years.

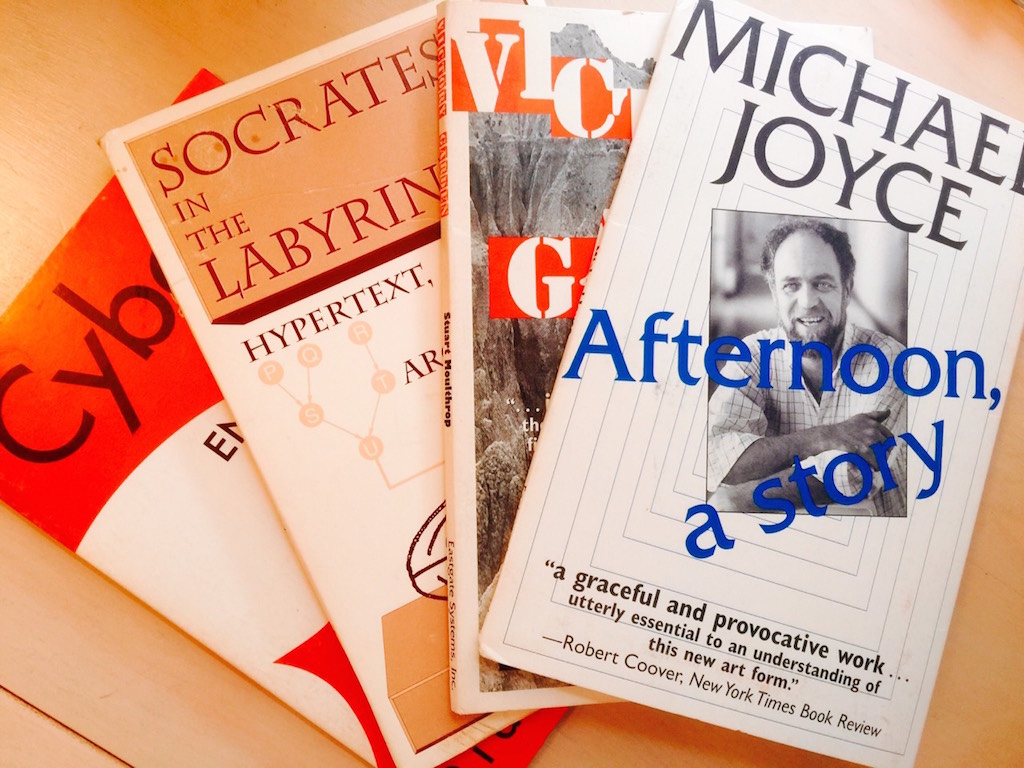

But, when computers began to have the ability to link digital documents, something strange began to happen to story. Some academics and authors, inspired by postmodernism and the power of computers, began to imagine hyperfiction. Hyperfiction is a form of narrative that can only exist on a computer. Its heyday was in the early ’90s when authors like Michael Joyce, Diane Greco and Stuart Moulthrop created works of hyperfiction that were driven forward, sideways and backwards through the associations and resonances between nodes of text. It was fiction as a game of Zork, a popular text-based game at the time. The idea of a story having a single, linear narrative road, was blown up and replaced with a tale that went madly off in all directions, depending on the choices of the reader.

Back then, I was a fan. Like the authors, I believed in the narrative power of hypertext. It just seemed natural to me that a new medium would spawn a new narrative form. We were all wrong. With a couple of exceptions, hyperfiction went exactly nowhere. That’s despite the best efforts of the foremost publisher of hyperfiction, Eastgate Systems, which also created software, Storyspace, with which authors created their work.

The general public, it seemed, didn’t want to work that hard for its stories. And I found, time and time again — I have quite a collection of hyperfiction — that I was disappointed and confused by the mesh of linkages that left me feeling like I just wanted a campfire and someone to tell me a story around it.

This all came back last week when I read that Google’s Creative Lab, in conjunction with Visual Editions, is developing Editions at Play, a “new kind of book: one which makes use of the dynamic properties of the web.” Oh, really? I think these folks may have been asleep in the early ’90s.

A few of the interactive books are now available through Google Play Books. I’ve looked through a couple of them, The Truth About Cats and Dogs and Entrances and Exits. And, while it is true, they are works of fiction that could not exist on paper, they are also works of fiction that are frustrating, confusing and feel like literary masturbation more than works of art.

I imagine these experiments will suffer the same fate as the hyperfiction of the early ’90s. I think humans like our stories told to us, not discovered by us in a labyrinth of links. Even when those stories are told backwards, as in Memento, by an unreliable narrator, as in The Usual Suspects or with reveals within reveals as in The Prestige, we like narratives that, when the pieces are assembled, tell a cohesive tale we can all agree we saw in whole, even though we may have different opinions about what it means, as in Inception. So, I no longer think different media engender different kinds of narrative. We remain, somewhere deep in our brains, toolmaking monkeys just looking for a fire, a shaman and tale to fall asleep to.

Listen to an audio version of this column, read by the author, here.

Wayne MacPhail has been a print and online journalist for 25 years, and is a long-time writer for rabble.ca on technology and the Internet.

Like this column? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.