Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Lately I’ve been watching the show Halt and Catch Fire. It’s an AMC series about the early days of the personal computer revolution. The show’s title comes from a machine language command that would cause a computer to have the machine equivalent of a rabid cocaine fit that could only be calmed by a reboot. So yeah, it’s for nerds, the way Mr. Robot and Firefly are.

In season two, a couple of the female leads start a gaming company called Mutiny. It offers online games, such as a very low-res version of Tank Battle. The games are played over snail-slow dial-up modems — almost as laconic as a Bell Fibe connection when school gets out.

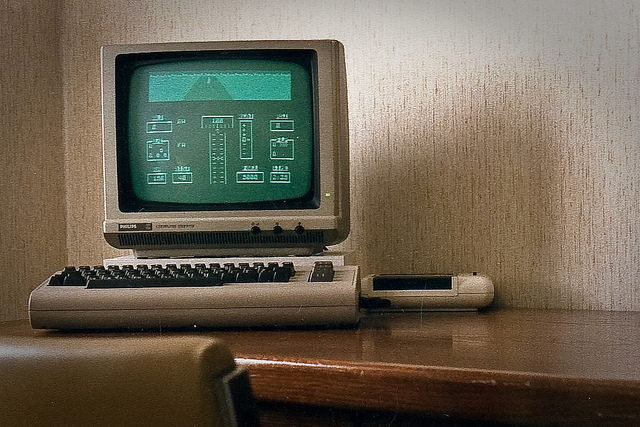

And here’s the thing that makes my nerdy and nostalgic heart ache. The games are being played and programmed on beige, plastic Commodore 64s. Back in 1983, I lived on that computer. I jammed it — along with a rattling dot matrix printer, a colour TV monitor and a kludgy modem — into a tiny closet off the living room of our rented apartment. Listening to the clack of the C64s’ keyboards on the show takes me immediately back to the geek fug and joy of that little room.

I knew every pixel and register of that machine. I programmed games on it using the BASIC language. It wasn’t as close to the metal as the Assembly language I had used with my first home computer, the Sinclair ZX81, but it got me far faster results. I could generate sounds and move snake-like sprites around the screen. I could make things happen. And, I was just a lowly amateur in a little room. I put up with the squawk and howl of a 300-baud modem to connect to the Quantum Link Network (soon to be AOL). I could talk to the world and discuss programming the C64 — because for me back then, there was nothing else worth talking about.

In the early ’90s, I was a relative latecomer to HyperCard, a remarkable Macintosh program that allowed users to create complex applications using graphic stacks and a scripting language called HyperTalk. I loved it and used it to create mock-ups for what I thought would be the newspaper of the future. But HyperCard was killed by Apple in 2004 and never made its way to OSX. It was the last time many amateurs like me could easily bend a modern graphic user interface computer to our will.

I mention all this because I’m now taking the first halting steps towards learning the Swift programming language. It is light years beyond BASIC and HyperCard. And I know that I will never get good enough at it to program anything halfway useful. And I miss that. I think it is a real shame that there is nothing like HyperCard for the Macintosh or BASIC for the C64: a simple, accessible language toolkit that allows non-programmers to feel some degree of mastery, invention and control. That mastery is what drives Halt and Catch Fire’s lead nerd, Cameron, as she rebels and codes with a fierce passion. In a small way, that’s also what drove me into my work now. Maybe learning Swift will give that back to me, but I don’t think so. For me, the days of Mutiny have passed.

Wayne MacPhail has been a print and online journalist for 25 years, and is a long-time writer for rabble.ca on technology and the Internet.

Listen to an audio version of this column, read by the author.

Photo: Luca Boldrini/flickr

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.