In late November, Statistics Canada released its latest data on hate crimes. The anecdotal and discrete experiences of many racialized communities were empirically validated. In 2017, hate crimes reached an all time high; I am worried but I am not surprised.

Since the tail end of the Stephen Harper government, as a visible Muslim woman, I felt a growing discomfort with my presence in public spaces. Usually my emotions remained unsubstantiated and since I generally do not want to give in to fear, I brush off many personal racist encounters. But when I hear reports of women’s hijabs are ripped off, when a swastika is painted on the side of places of worship or when a poster comparing the prophet Mohamed to Hitler appears, my worst suspicions are confirmed.

The StatsCan data demonstrates there has been an increase in the number of hate crimes and their gravity, against Muslim, Jewish and Black communities in the last three years. What the data does not show is how this targeted and racialized violence operates intersectionally. Like I wrote in The Leveller in September, class, gender, immigration status, and race, and other identifiers, work in tandem when it comes to manifestations of discrimination. Anecdotal evidence shows that black Muslim women face violence at the crux of Islamophobia, misogyny and anti-black racism.

Last year, in the aftermath of the Quebec mosque shooting, Liberal member of Parliament Iqra Khalid tabled M103, a non-binding motion to explore Islamophobia and religion discrimination in Canada. As a result, she received multiple hateful threats, many to her life. The motion, which has no legal clout, rallied hate groups and mobilized fear-driven politics.

Ultimately M103 passed in the House of Commons and the standing committee on Canadian Heritage heard from various faith groups, grassroots organizations and academics on the topics. Many witnesses spoke firmly against racial and ethnic hatred, including anti-black, anti-Indigenous racism, and anti-Semitism. A total of 30 recommendations were made but no pressings actions were demanded of the federal government. The report lightly touched on intersectionality, with witnesses, like activist and professor Dr. Cindy Blackstock emphasizing its importance. Although, recommendation No. 12 acknowledges the adoption of intersectionality in the development of public policy, it does not present it in its recommendations on data collection and reporting of hate crimes.

In the United Kingdom, an all-party report on Islamophobia proposed a working definition of the term, stating: “Islamophobia is rooted in racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness.” It considers, therefore, attacks on those who are, for instance, Arab and not Muslim or Shiks who are attacked on the assumption they are Muslim (data shows both these scenarios occur in Canada). The report complements academic research and community consultations with stories of lived experience, highlighting human voices in a conversation often dominated by statistics.

The report considers the specific nature of gendered Islamophobia and explains the psychological distress female-identifying victims experience following a hate crime. It details how women, in particular, reconsider performing their gender and religion in public spaces after threats to their identity and security.

At the vigil for the six Muslim murdered men in Quebec City in early 2017, politicians from all parities were eager to engage in the optics of mourning. Yet, neither the prime minister nor the minister of Canadian Heritage, Pablo Rodriguez, has announced concrete steps to prioritize combating racial and religious hatred. An important first step would be for the federal government to designate Jan. 29 a national day of action against hate and intolerance as recommended by more than 100 Canadian organizations. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Islamophobia is real in the aftermath of the mosque shooting, and yet, his government’s actions do not echo to that stand.

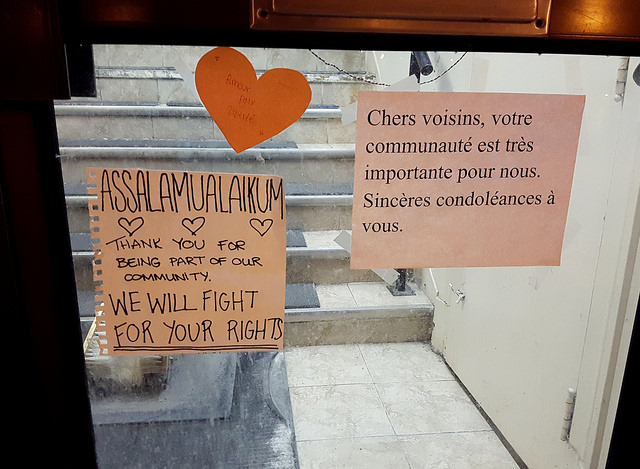

A common and loaded accusation is that these criticisms of Canadian society work against freedom of expression and association. I disagree; advocacy to make our streets, campuses and workplaces safer is a service to all of society. We have countless anecdotal reports along with raw data to show we are failing our must vulnerably systemically and socially. Racialized communities do not have to prove their victimhood or their marginalization. We owe it to our Canadians to develop a robust, intersectional and human-centred approach to combat gendered and racialized hatred.

Barâa Arar is a recent graduate of Carleton University’s College of Humanities with a focus on art, politics and resistance. She is a community organizer, writer and the co- host of The Watering Hole podcast. You can find her at: www.livewellspoken.com

Photo: Coastal Elite/Flickr

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!