“We are just here to ask you some questions Syed.”

Said the younger, shorter man who introduced himself as Ryan. This other one said his name was Dave. “We are from the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Air Marshall Service.” Badges flashed and taken away.

Its 9:30 a.m. on Thursday, July 28, 2011. I’ve just been put in an interview room with blood stains on the floor and clothes strewn around. I’ve been at the United States border, the Peace Bridge, since 4:45.

“I understand you are under house arrest, Syed.”

“No, I am not.”

“I see, why are you trying to enter the United States today, Syed.”

I’ve already been interrogated by Customs and Borders Patrol, by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, by plain clothes men that declined to introduce themselves and I am exhausted.

“Look as I told the last five people, I was arrested with 1,100 people during the anti-G20 protests in June 2010, and I am awaiting trial. My house arrest was lifted a month ago. My mom was diagnosed with cancer last week, she’s just had surgery and I need to go see her. I am just here to go to the Canadian consulate, get a Canadian re-entry visa, so that I can get back into Canada on my way back from Pakistan. I have had my bail conditions changed to allow that. The embassy closes in 30 minutes, why am I being held here?”

(I’ve spent the last two weeks to prove to the Crown that she is indeed my mother, and that I am not lying about her illness, begging to get my passport back.)

“We’d just like to ask a few questions,” Dave says.

“Do you know anyone who holds extremist opinions?”

“Do you know anyone who intends to destroy the United States government?”

“Do you believe the United States should not be a member of the G20?”

“Are you working as an agent for a foreign government?”

“Would you like to share information with the United States government about extremist elements?”

“Are you worried about the political situation in Pakistan?”

“Do you believe the United States government has exacerbated the political situation in Pakistan?”

“Would you like to help us?”

“Do you condone violence?”

“Do you know anyone that has ever counselled violence against the United States government, its allies, or its institutions?”

“If you knew any of this, would you share this information with the U.S. government?”

“Please list all U.S. citizens you’ve associated with in the last five years.”

“Have you taken part in violent activities?”

“If you were made aware of violent activities, what would you do with this information?”

“Are you aware of anti-government elements in the United States?”

“Why were you born in Libya?”

“List every address you have lived in since birth”

“Describe the protests that took place against the G20.”

This goes on and on and on. I answer. Knowing that I had to avoid lies, as well as statements they did not agree with.

At 1 p.m., I’m told I will be let go. My entry visa has been cancelled by the Department of State, for unknown reasons at an unknown date. I’m asked to sign papers saying that I understand this.

At 1:15 p.m., I am strip-searched, shackled, handcuffed to a chain around my waist, driven three minutes across to Canada and handed over to Canada Border Services Agency and Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

The questions start anew.

“Are you in contact with the people that were responsible for the crimes you are alleged to have committed?”

“Have you come in contact with any law enforcement body in the last year?”

“How do you feel about the political situation in Pakistan?”

At 2 p.m., I am let go and start the drive back to Toronto. I am still in Canada. I could still go to Pakistan to see my mom, but I would then have no way of getting back to my friends and community in Toronto.

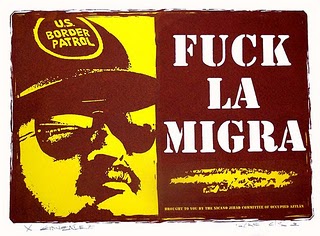

We have to do something about these borders.