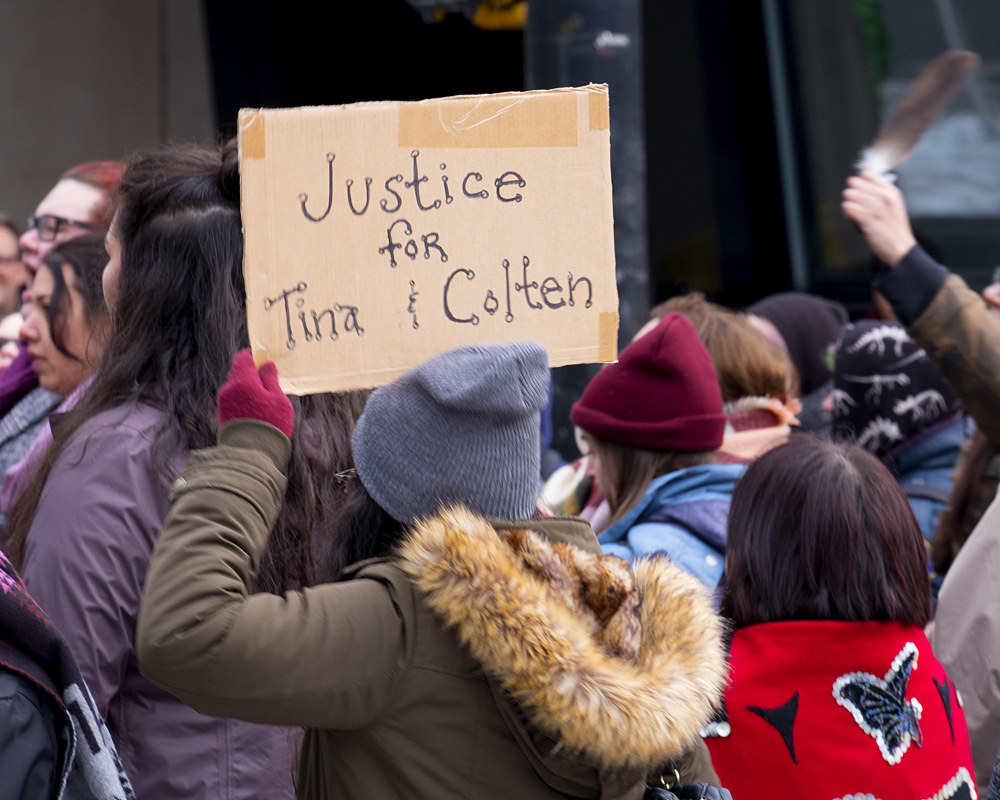

The violent deaths of Colten Boushie in Saskatchewan and Tina Fontaine in Manitoba hit their families, communities and First Nations pretty hard. These were youths who had their whole lives ahead of them. The fact that deep-seated institutional and societal racism and violence against Indigenous peoples is what led to their deaths is a glaring injustice that we have seen happen many times over to our people. But the other glaring injustice is how institutional and societal racism and violence allows the killers of our people to walk free. The high level of impunity for lethal race-based violence against Indigenous peoples serves only to reinforce the racist idea that Indigenous lives don’t matter. Without intervention from federal, provincial and municipal governments, agencies and police forces, our people will continue to be at risk.

Canada’s failure to act on this crisis means that First Nations must continue to take action to stand against these injustices which are killing our people. At a time when our hearts were collectively breaking over the non-guilty verdicts in the Gerald Stanley murder trial of Colten Boushie and the Raymond Cormier murder trial of Tina Fontaine, First Nation members from Saskatchewan got together and created the Justice for Our Stolen Children Camp. On February 28, 2018, they raised a traditional teepee and lit a sacred fire in Treaty 4 territory at Wascana Park, just across from the Saskatchewan legislative building. These grassroots community members used their most powerful tool to bring attention to this crisis — their voices and their traditions.

But the teepee and the sacred fire not only attracted media attention for our issues, it also turned into something special. This camp became a gathering place for those who had lost children to violence, foster care and the justice system. Mothers, fathers, aunties and cousins with broken hearts came to the camp to share their stories, release their emotions and start their healing journeys. Far from creating any safety risk to the public, this camp offered hope, comfort, solidarity, a sense of collectiveness and empowerment. The longer the camp remained at Wascana Park, the more the media took notice and started to highlight the many injustices faced by First Nations. The core message from the camp was that we need justice specifically for Indigenous youth in the wake of the Stanley and Cormier not guilty verdicts; and justice for the many Indigenous children stolen from our communities by child welfare agencies, the justice system and societal violence.

For many months, it may have appeared to outsiders looking in, that they were alone and that their camp would eventually fade from attention. They occupied the area peacefully for four months, supported by donations from First Nations and allies. It wasn’t until the Province of Saskatchewan thought the camp would interfere with its planned location for its Canada Day beer gardens that they took legal action. On June 5, the camp was issued and eviction order and 10 days later, the Regina Police Service began their eviction procedures by removing the tents. On June 17 the teepee was taken down and on June 18 six of the campers were arrested and removed from the area, though charges were never laid. Many of us watched with anger as the province carried out this heavy-handed action, trampling over the wounded hearts of those who have found some temporary peace at the camp — all for the sake of beer gardens.

But if there is one lesson from our elders that we have to remember, is that we can never give up hope. Our ancestors died protecting the rights of future generations not yet born. We inherited the obligation to face each barrier put in front of us by colonial powers, with the same commitment to overcoming it, as our ancestors had. So, on June 21 National Indigenous Peoples Day, when we saw videos of the campers returning to Wascana Park, re-erecting the teepee and joining together in a round dance, our collective hearts were lifted again — this time with a renewed sense of resistance and empowerment. On June 23, a second teepee was erected and others joined in solidarity after that until there were many teepees side by side. People made donations of cash, food and water to support the campers and the healing continued. We owe so much to the spirit and determination of those who have stayed at the camp for long. Their commitment is why we are still talking about justice for our stolen children.

There is a real and growing crisis in Saskatchewan that demands an emergency, crisis-level joint response by federal, provincial and First Nation governments, experts and advocates. It doesn’t matter what the federal or provincial governments say they have done, what programs they have funded, or who they talk to at various discussion tables — what matters is that what they have done to date has not worked and the crisis continues to get worse. Therefore, a radical shift from the status quo is required to save the lives of our children. They don’t have a whole childhood to wait for the slow, drawn-out process of policy change. Our children are dying and the statistics present a dire picture for their life chances if we don’t change this now.

Child welfare

In Canada, Indigenous peoples make up five per cent of the population and Indigenous youth make up seven per cent of the youth population. Nationally, Indigenous children make up 48 per cent of all children in foster care — a number that is three times higher than during the height of residential schools. However, in Saskatchewan, an alarming more than 70 per cent of children in provincial care are Indigenous and the numbers continue to increase. We know that less than half of those children will graduate from high school and more likely to end up in youth corrections. The statistics also show that that Indigenous girls in foster care are four times more likely to be sexually abused; more likely to be targeted for human sex trafficking and are over-represented in murdered and missing Indigenous girls. The theft of our children into foster care does not just impact the children. Indigenous mothers who lose their children to foster care are more likely to die from heart disease and suicide.

Justice system — prison

Canada has had the lowest crime rate since 1969 with a reduction of 34 per cent since 1998. Yet Indigenous people make up more than 26 per cent of those in federal prisons and Indigenous women make up 34 per cent. Saskatchewan’s numbers are frightening. Over 76 per cent of admissions to Saskatchewan prisons are Indigenous — the highest rates in Canada. Nationally, 41 per cent of youth in corrections are Indigenous, with 51 per cent being Indigenous girls. In Saskatchewan youth corrections, 92 per cent are Indigenous boys and 98 per cent are Indigenous girls. They have the highest youth incarceration rates in the entire country. More than one-fifth of Indigenous prisoners were in residential schools and two-thirds were in the child welfare system. It is important to remember that Indigenous peoples represent one-third of all suicides in prison and more than half of those who suffer in solitary confinement/segregation.

Violence — state and societal

In 1996, the report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples noted that racism is rampant from police forces to the courts. Saskatchewan policing in particular has a long, violent history of racism against Indigenous peoples. In 2004, the Saskatchewan Commission on First Nations and Metis Peoples and Justice Reform found that racism in policing was a “major obstacle” in relations with First Nations. The well-known police practice of “Starlight Tours” where police detain and drive Indigenous men to the outskirts of town where they freeze to death doesn’t seem to have ended with the Neil Stonechild inquiry. Indigenous women are often targeted with sexualized violence — including from police. The Human Rights Watch report from 2017 documented instances of excessive use of force, abusive strip searches and other sexual harassment against Indigenous women. The statistics also show that Saskatchewan has the highest rate of police involved deaths (beatings, chokings, shootings) of Indigenous peoples (62.5 per cent).

The RCMP report into murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls showed that nationally Indigenous women and girls make up 16 per cent of those murdered, but in Saskatchewan, that number jumps to 55 per cent. Societal violence comes from the places most people do not suspect: priests, farmers, police, corrections, doctors, lawyers, judges, social workers, teachers, and foster parents. Very few of those who sexually violate or murder Indigenous women and girls are serial killers. The statistics also show they are less likely to be murdered by their spouse than Canadian women. The high level of impunity (non-conviction) for those perpetrators in society who continue to commit violence against Indigenous peoples is exacerbated by the many reports that document how police fail to protect Indigenous peoples or properly investigate their cases.

We have a real crisis in Saskatchewan. What has been done isn’t working. We need a new approach — one that is led by First Nations and their experts and advocates. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to the campers at the Justice for Our Stolen Children Camp who have sacrificed their time and energy, and risked police arrest and jail, to keep the light on this crisis. We don’t want to lose any more of our children and we want to bring the rest of our children who are in foster care, corrections, trapped by human traffickers, or missing — back home. Bring our children home.

In memory of all those precious lives those and sadly, too many to name:

Neil Stonechild, Leo Lachance, William Kakakaway, Leonard Paul John, Colten Boushie

Nadine Machiskinic, Shelley Napope, Melanie Dawn Geddes, Amber Redman, Danita Bigeagle

Haven Dubois, Brandon-Bee Ironchild, Evander Lee Daniels

Please see my YouTube video that I have created in support of the Justice for Our Stolen Children Camp.

This article was originally published on Pamela Palmater’s blog on August 23, 2018.

Photo: Memaxmarz/Flickr