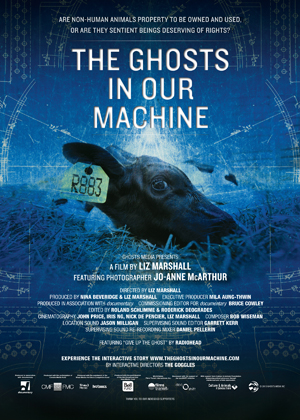

The film “The Ghosts in Our Machine,” directed by Liz Marshall, is a view of the animal rights issue through the lens of Toronto photographer Jo-Anne McArthur. The film posits that animals are not an insentient resource to be mechanistically processed, but a separate nation. Humanity is making imperial war on this nation, and Jo-Anne McArthur is a combat photographer.

McArthur makes an international career of documenting the inhuman misery that capitalism visits upon animals. She has worked with numerous animal rights campaigns documenting the horror that are the lives of billions of animals treated as system throughput rather than sentient beings. Her photographs are haunting both to herself and the viewer. Her lens gives meaning to lives lived only to gain protein mass, fur or some other commodity traded and consumed by human beings.

In the scenes where McArthur infiltrates a fox fur farm, the banality of the evil that is fur is immediately apparent. The foxes are caged, exposed and miserable. As a European animal rights activist enumerates the number of foxes that are raised and killed in this single operation, it becomes apparent that billions of animals are born, live and die in conditions tantamount to life long torture.

Despite “advanced” animal protection legislation, most animal cruelty is concentrated in the developed world. For that reason industries exploiting animals fear the right photograph more than property damage or animal liberation direct action.

It will be people who will eventually end animal abuse. This will only happen when the suffering of animals is unavoidably evident. Insurance will cover property damage and stock loss, but the idea that there is no more god given right to exploit other species than to exploit other races is the biggest threat to the status quo.

An eventual acceptance of basic animal rights will occur like the end of slavery, or universal suffrage. It will take a critical mass of awareness. McArthur is clear in her purpose. She is not there to liberate individual animals. That would not change the system that is geared to exploit them. She is there to add to the critical mass of awareness needed to render the concept of animal rights as normal as that of human rights.

McArthur is personally haunted by the life of one chimpanzee, Ron, whose image is truly poignant. Despite a life of enduring medical experimentation, Ron forgave humanity for the horrors of his existence. The picture of Ron is heartbreakingly anthropomorphic. If we can abuse a creature separated from ourselves by so few degrees of evolution, what hope does a rat or mink have.

But McArthur’s photographs show us the animals we don’t want to see: the beagles bred for torture, the highly intelligent marine mammals imprisoned in water circuses, and the trailers full of pigs trucked to slaughter in a Toronto urban slaughterhouse. These are all animals who we don’t want to view outside their normal context. Everyone loves images of majestic wildlife, or cute cats. What nobody wants to see is billions of animals being processed into product. The machinery of modern life is greased with the suffering of sentient creatures, but it’s best if no one questions what makes the machine run so smoothly.

Recent legislative gambits may actually render McArthur’s craft illegal. The factory farming industry has sponsored many bills to make photographing slaughterhouses a crime. The success of photographers like McArthur in advancing animal rights can be measured directly by the efforts of animal exploitation industries to have their profession criminalized.

The farm sanctuary sequences in Ghosts in Our Machine show one of the last contexts within which human beings form actual connection with farm animals. Most real farms are protein factories wherein animals are commodities and no regard is given to their sentience. The tranquility of farm sanctuary is a welcome counterpoint to the film’s merciless displays of industrial and scientific cruelty.

The difference between the life of an animal in a sanctuary and an animal in the machine, is the difference between heaven and hell. Piglets at the sanctuary are things of beauty enjoying happiness. The fact that their mother was the subject of torture by cattle prod seems an incongruity, rather than the brutal norm.

The film moves slowly and deliberately. It is richly shot, and has a lingering ambient and atmospheric soundtrack by Bob Wiseman. The film’s atmosphere does not reflect the noise and pain of the lives of the animals caught in the machine. What it does reflect is the inner tranquility of McArthur, who, though haunted by what she has seen, is at peace for knowing she is doing whatever she can to ameliorate the existence of billions of creatures.

Upon meeting with a Newsweek editor she whispers: “I’m trying to save the world” in a way that is self-consciously exaggerated. This is pure insight. The secret to tranquility is a life spent in good humour, pursuing a higher purpose.

After a creature is consumed in the machine, a McArthur photograph is usually the only thing documenting its miserable existence. There are cultures that believe that a photograph steals the spirit of its subject. McArthur’s photographs actually accomplish the opposite. They are often the only haunting trace of an entire existence; ghostly representations of billions of lives lived in horror.

Humberto DaSilva is a union activist whose ‘Not Rex Murphy’ video commentaries are featured on rabble.

For more film reviews, see our Film Festivals in Toronto page.