It’s membership time. Cultivate Canada’s media. Support rabble.ca. Become a member.

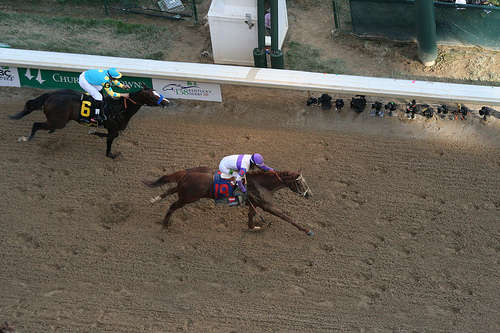

The final jewel in Thoroughbred horse racing’s Triple Crown has been won by Union Rags, an impressive animal with a smile-igniting name. But the politics of our metaphorical and literal relationships with horses are still going strong.

Canadian-owned I’ll Have Another had the potential to become the first Triple Crown winner since 1978, upping the excitement for the Belmont Stakes. In the world of elite Thoroughbred horse racing, well-pedigreed yearlings can sell for millions of dollars.

I’ll Have Another was bought for $11,000. He was passed over by many, and was truly a long shot. As a result, the excitement was because of our admiration for a lightning fast chestnut colt. But it was also because people blur the boundaries between human and animal, and turn horses into metaphors onto which we saddle our frustrations, and our hopes.

Contemporary racing involves hundreds of thousands of people, from very low wage grooms toiling long hours behind-the-scenes, to working class owners who train their own harness horses to compete on local tracks.

But top level horse competition is widely considered a playground of the rich. So when a horse who isn’t born or expected to win, wins in that arena, the animal becomes larger than life. Certainly there are expensive and well-pedigreed champions who are honoured, but the underdog horses really capture our imagination.

Snowman, a former plough horse featured in a popular biography, was bought for eighty dollars on his way to a slaughterhouse, yet he went on to win top level show jumping classes. Neville Bardos was first saved from slaughter, and then survived a horrific barn fire one year ago. Now he is a strong and admired contender for the U.S. Olympic eventing team.

Canadian show jumping legends Big Ben and Hickstead were both unexpected champions. 2010 race horse of the year, Zenyatta, was not only bought for a lower price, but she is female. In a sport dominated by male horses, she is heralded as a champion and for breaking an equine glass ceiling.

The most famous equine embodiment of the rags to riches motif is Seabiscuit. This great horse twice rose against massive odds, inspiring millions of unemployed and poverty-stricken workers during the Depression.

Today, as the threats of job losses and lay-off notices keep coming, whether due to Harper’s cuts or the decisions of foreign companies like Caterpillar and Target, people are again looking for sources of hope.

The vast majority of us are not born socioeconomic winners, and it is becoming tougher to hold ground, let alone get ahead. The current North American economy is designed as a pyramid, so there can only be a minority of victors. But much attention is paid to those on top. And how working class people feel about the very rich is complex and varied. It involves feelings of envy, shame, anger.

These ideas about wealth and class are projected onto equines. Underdog horses who win can suggest that those without economic and cultural privilege can sometimes make it big, despite stacked odds. Some people like to hold onto this dream, however slim it is. Underdog horses who win can also symbolize beating the rich at their own game, thereby providing a kind of catharsis or revenge, however fleeting.

Although they are not usually explicitly called workers, horses have done a lot of work. They have hauled goods, building materials and people. They have been harnessed for war, ranching, mail delivery, law enforcement and people’s leisure, sport and entertainment. And by focusing primarily on the victors, whatever their background, our attention is turned away from the vast majority of horses who do not win marquee races, but whose lives nevertheless matter.

Snowman and Neville Bardos were saved, but tens of thousands of horses of all ages are killed in slaughterhouses every year in North America. This reminds us that horses are more than metaphors. But they are also more than commodities. They are living and feeling beings.

Damage to I’ll Have Another’s body halted this stage of the latest famous underdog’s literal and metaphorical journey, but thankfully not his life. And jockey Mario Gutierrez still calls the horse his hero. But far too many horses are seen as disposable. Too few go onto second careers, welcoming homes, or peaceful retirement.

It is an interesting time for all lives interwoven with horse racing. Horse people in Ontario are engaged in a struggle with the McGuinty government over track and slots closures, as well as revenue from the slot machines housed at race tracks. Tens of thousands of jobs are at risk, as are horses’ lives. But racing folks and horse people of all stripes are joining with the labour movement in Ontario, and promising new coalitions are being formed among rural, urban, union, and non-union workers. So this is an ideal moment to think about the well-being of human – and equine – workers in the racing industry.

We can celebrate the winners of the big races, but individual and symbolic victories are not enough. We deserve more, and so do the horses. If we really want to celebrate horses and everything they do for us, we can provide them with greater dignity and respect, during and after their working lives. Real hope lives in compassion and solidarity, within and across species.

Kendra Coulter is an anthropologist and professor who will be joining the Centre for Labour Studies at Brock University in July. She is currently at the University of Windsor.

A list of horse rescue, retirement, and adoption agencies is available here.

An earlier version of this article was published in the Guelph Mercury.