The Assembly of First Nations will hold its election for national chief on July 25 in Vancouver. Only the chiefs of the 634-plus First Nations are eligible to vote but most chiefs’ assemblies see less than half of those attend, and of those, many are proxies and not actual chiefs.

While elections for prime minister, premier and even mayors attract nightly political commentary, analysis and predictions in the months and weeks prior to their elections, there is generally very little commentary about the AFN election outside of Indigenous media like APTN, Windspeaker or smaller Indigenous political blogs. Yet, what is at stake in this election for First Nations should be of great concern to Canadians.

This election feels more like a boiling point — a critical juncture spurred by the growing discontent of the AFN that was apparent in the last three AFN elections for National Chief. The outcome of this election could change everything for the better or the worse and Canadians will be impacted either way.

The colonial reality of First Nations impoverished through the dispossession of lands and resources, together with an aggressive and unrelenting assimilation policy, forces leaders to make hard decisions in order to provide relief for their people. Their own local elections depend on whether houses are built on reserve to relieve the crisis-level over-crowding and homelessness or whether there is access to safe drinking water and food to keep their children out of foster care.

The focus of local First Nation elections is often based on life and death issues — a far cry from federal or provincial elections which tend to focus on the best interests of the middle class, tax relief or international trade. The AFN is well aware of this dynamic in First Nations and uses the fear of losing critically needed social programs and services as a means to garner support for federal policies — which in turn equate to more money for the AFN itself. While everyone is aware of this dynamic, the need to provide for First Nation citizens is often paramount.

Historically, First Nation leaders addressed their concerns privately, but the AFN’s drastic departure from its original purpose as an advocacy organization risks the very rights of First Nations, thus requiring the very public pushback we have seen in recent years.

What is happening both before our eyes and behind closed doors is an epic battle to protect First Nation sovereignty, lands and cultures. It is a battle that seeks to frame reconciliation as more than the beads and trinkets offered by the Trudeau government and one which aligns more with First Nation constitutional and international rights.

This election will be a contest between those who accept the federal government’s legislative framework agenda in exchange for relatively minor (but desperately-needed) funding increases to programs and services versus those who reject it, and demand the return of some of their lands, a share in their natural resources, and the protection of their sovereignty and jurisdiction. Either path will result in significant consequences for First Nations. But make no mistake — there will be government retaliation if the election choice is real reconciliation.

Sadly, this is not a battle of their own making. Most of the divisions amongst First Nations have been created and maintained by federal bureaucrats, who have maintained their vise-like grip on the so-called “Indian agenda.” Even the first few attempts at national political organizing among First Nations after the First and Second World Wars were defeated by government interference.

While the National Indian Brotherhood started out strong in defence of core First Nation rights and title, more recent years as the re-named Assembly of First Nations have seen a drastic decline in advocacy and a corresponding increase in the support of federal agendas. While most of the federal pressure occurs behind the scenes, the previous Conservative government wielded social program funding and federal legislative power as a weapon to bludgeon any attempt to advocate for First Nation rights. Former Prime Minister Harper’s government enacted a historic amount of legislation against the will of First Nations and even threatened to cut funding for “rogue chiefs” who dared challenge their legislative agenda of increased federal control over First Nations.

While Trudeau was elected on a promise to repeal all of Harper’s legislation, he hasn’t done so — nor will he ever. He has his own legislative agenda designed to build upon Harper’s increased legislative control of First Nation governments by also limiting the scope and content of First Nation constitutional rights and powers once-and-for-all.

The Trudeau government seeks to define and limit the scope of First Nation rights and powers under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 in federal legislation under the guise of reconciliation. Therein lies the Trojan Horse of Trudeau’s brand of reconciliation. Trudeau’s reconciliation, while flowery and tearful, will result in the legal assimilation of First Nations into the body politic. Something his father, former Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, tried to do with the 1969 White Paper on Indian Policy designed to get rid of Indian status, reserves and treaty rights.

Real reconciliation — which is about addressing the wrongs of both the past and the present — requires the transfer of lands and resources back to First Nations, the sharing of the wealth made in First Nation territories and the full recognition of First Nation sovereignty and jurisdiction (the right to be self-determining). However, most Chiefs are acutely aware that although this is the path that most honours our ancestors and coincides with our rights; it is also the path with the most severe consquences. The path of retaliatory reconciliation has always attracted the full force of Canadian law enforcement and military power.

When the Mi’kmaw Nation at Listuguj tried to manage their own fishery in the 1980s, they were brutally beaten and arrested by the Surete du Quebec (SQ) police. When the Mohawks of Kanesetake tried to protect their traditional territory and burial grounds from a golf course in 1990, the SQ, RCMP and military laid siege to their territory for months.

In 1995, an unarmed land defender named Dudley George was killed by Ontario police for protecting his reserve lands at Ipperwash. In the same year, the RCMP launched the largest attack on ever on a civilian population at Gustafsen Lake — all to prevent a small group of sun dancers from performing their ceremonies on so-called Crown lands.

Even once the Mi’kmaw Nation at Esgenoopetitj (Burnt Church) had proven their treaty right to fish at the Supreme Court of Canada in 1999, the RCMP and DFO used brutal force to stop the Mi’kmaw from fishing. Hundreds of RCMP SWAT forces were called out to suppress the peaceful resistance of the Mi’kmaw Nation at Elsipogtog to hydro-fracking on traditional lands.

Sadly, Canada’s vision of reconciliation only works if First Nations don’t assert their rights. First Nations are more than welcome to enjoy their powwows, re-name streets in their languages or hang their art in public spaces, as acts of multi-culturalism. But when it comes to asserting inherent, treaty or constitutional Aboriginal rights and land title — that is where Trudeau’s vision of reconciliation breaks down. One need only look at the arrests related to protests against the Trudeau/Kinder Morgan Pipeline to know where real reconciliation is headed.

Canadians should be very concerned about the actions of their governments towards reconciliation and what this AFN election means for the safety and well-being of Indigenous peoples moving forward. After all, as beneficiaries of the treaties, Canadians have a role to play in addressing historic and ongoing wrongs.

There is no way to sugarcoat what is at stake in this AFN election. A vote for Perry Bellegarde is a vote down the rabbit hole of assimilation that looks eerily like a pipeline. A vote for real reconciliation means First Nations will have to brace for retaliatory impact — but this is the only path that will protect our rights from voluntary erasure.

Full disclosure: I was the runner-up candidate in the AFN election 2012 to the former incumbent National Chief Shawn Atleo.

This article was originally published in Lawyer’s Daily on July 18, 2018.

Postscript:

I would like to refer you all to two very good articles written by Indigenous commentators on the AFN election. Both Niigaan and Doug are excellent writers and have a great deal of insight into First Nation political issues.

1. “National chief election matters” written by Niigaan Sinclair for the Winnipeg Free Press on July 7, 2018.

2. “Changes needed to AFN structure” written by Doug Cuthand for the Saskatoon StarPhoenix on July 14, 2018.

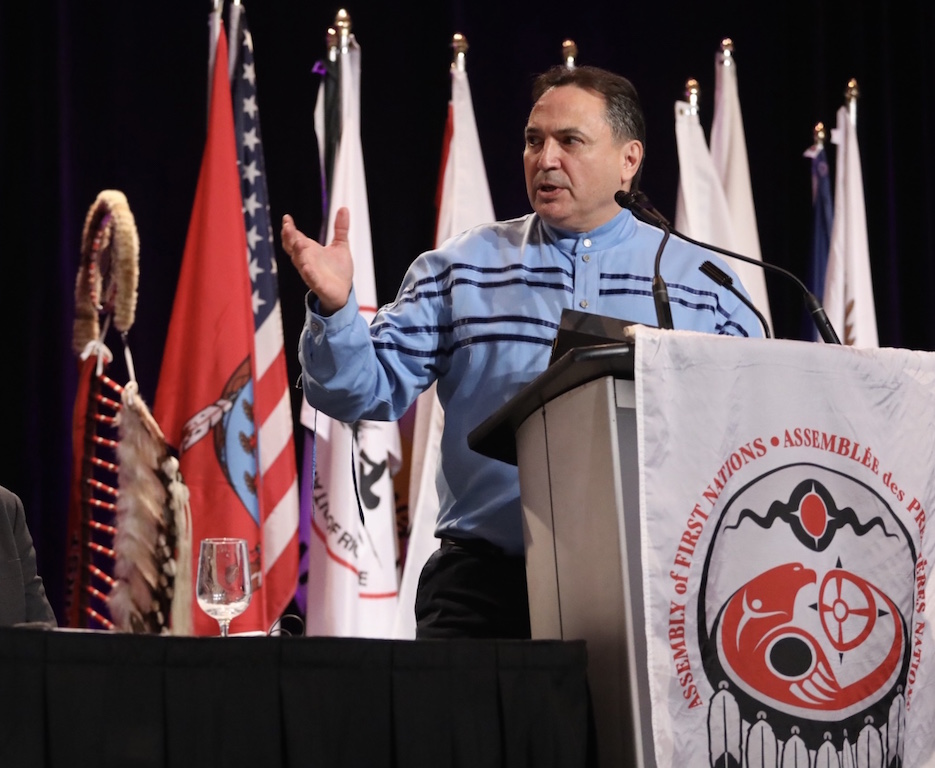

Photo: Andrew Scheer/Flickr

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.