Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Matthew Heineman’s Cartel Land is a 2014 documentary that describes itself thus:

“With unprecedented access, CARTEL LAND is a riveting, on-the-ground look at the journeys of two modern-day vigilante groups and their shared enemy – the murderous Mexican drug cartels.” [From the Cartel Land website.]

And as stated the film is divided into two parts: One follows a self-defense or auto-defensa organization in the state of Michoacán, Mexico, a region currently in the grips of violence between competing drug cartels. The other section of the film follows a group of US vigilantes on the Arizona/Mexico border. The two stories are interlaced, and the two situations are juxtaposed without comment.

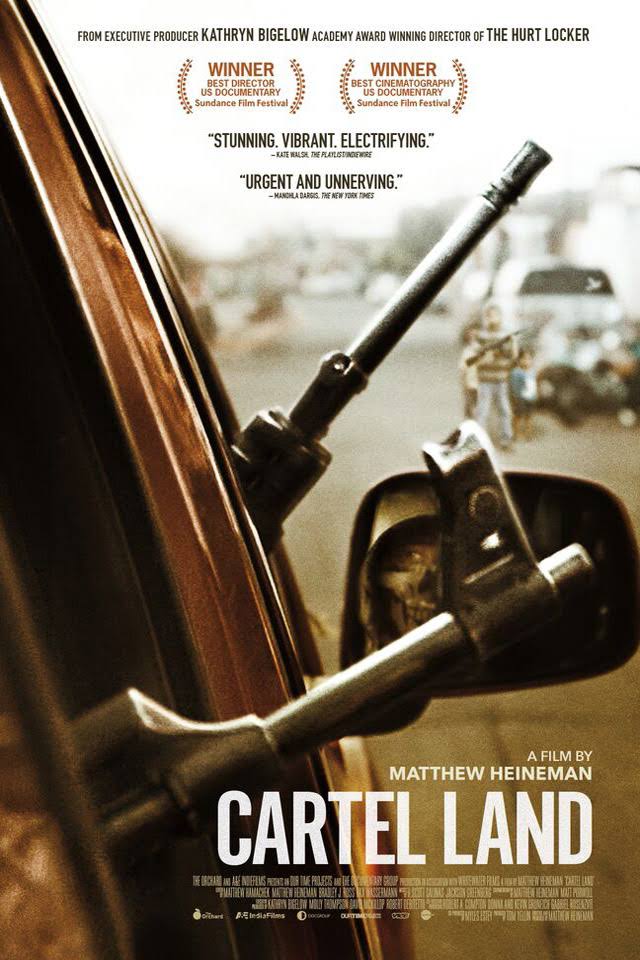

Brilliantly photographed and containing excellent access to all sorts of impressive footage, including actual firefights captured on film, Cartel Land netted “Best Director, U.S. Documentary” and “Best Cinematography, U.S. Documentary” from the 2014 Sundance Film Festival.

The first section of the movie is about Michoacán, Mexico, specifically Dr. Jose Mireles, who is one of the main organizers of his local autodefensa group, which was organized to defend against the extremely violent drug cartel known as Los Templarios who operate in the area. In the past decade such autodefensa groups as this one have sprung up around Mexico as the government fails to protect its own citizens and people around the country, particularly in regions wracked by drug-violence, have responded by taking matters into their own hands. I myself reported on the earliest of such groups, La Policia Comunitaria, here.

The camera follows Dr. Mireles as he travels his region of the state garnering support, giving speeches, passing out literature, recruiting, and organizing patrols against Los Templarios. These sections of the film are somewhat breezily edited, giving the impression that the success and the popularity of the autodefensa organization is growing daily at leaps and bounds. Given the grave nature of the situation one can’t help but be suspect that the situation is not quite as simple as it appears. This seems to me to be a recurrent problem when Hollywood (or in this case, HBO) produces documentary films: too often the story is force-fit into a convenient “narrative arc” even when the reality may be much more complex, as the truth usually is.

In fact a group of Mexican independent journalists, Subversiones, wrote a critique of Cartel Land that pointed to the film’s overly simplistic portrayal of Dr. Mireles entitled “A Myopic View Of The Reality In Michoacán” which can be read in Spanish here.

But it is the other section of Heineman’s film that I want to address more at length. He juxtaposes the Michoacán autodefensa organization — people organizing against murderous narco-gangs that are in cahoots with the Mexican government — with a group of vigilantes who patrol the U.S. side of the Arizona/Mexico border in an attempt, as the film’s description puts it, “to prevent Mexico’s drug wars from entering U.S. territory.” The group are self-organized and appear to number, based on what we see in the film, roughly 5-20 individuals. They wear camouflage, carry powerful automatic rifles, and their main activity is patrolling border. They call themselves Arizona Border Recon, and director Heineman spends a great deal of time with them, following them on night patrols and recording their explanations of why they do what they do. And by comparing these paramilitary fascists with the Michoacán autodefensa organization, without comment, he is posing them as moral equivalents.

This is a problematic if not ridiculous comparison on many levels. Firstly, the main market for drugs produced in Mexico has always been the United States. So if one really wanted to neuter the power of drug dealers in the U.S. the solution would be to de-criminalize drugs, as has been being espoused across the political spectrum including by right-wing libertarians for several decades now. Also, as Mexican government officials are quick to point out, most of the weapons used by the narcos are procured in the US. And let’s not forget the biggest winners in all of this: banks like HSBC, who were referred to by a Mexican cartel as “the place to launder money”. So in that sense the Mexican drug trade is already deeply intertwined with the United Sates economy and has been for a very long time.

And there are indeed cartel operatives working in the United States. But they don’t walk across the border into Arizona with a backpack full of cocaine. While there are some drug “mules” used to haul narcotics by foot into the U.S., there is simply no way that that could account for the lion’s share of illicit drugs entering the U.S. from Mexico. Cartel operatives in the U.S. are either “recruited” in the U.S. (which usually means that the cartels threaten to boil their families in acid back in Mexico if they don’t cooperate) or sent by the cartels to oversee operations in places like Chicago or Georgia.

As I watched the footage in Cartel Land of this group of paranoid white guys with automatic rifles wearing camouflage troop around the desert insisting they are “defending” the U.S. from drug cartels, I almost laughed. Do they really think that cartel members are trying to enter the U.S., overland, across the Arizona desert? The cartels are already here, as are their customers (the U.S. population).

And indeed, who do we witness the Arizona Border Recon actually apprehend on one of their patrols of the border, in the film? The founder of A.B.R., Tim “Nailer” Foley insists that the Mexican cartels have “scouts” in the region of the desert he patrols, and that these scouts keep evading his attempts to apprehend them. Which begs the question, never asked by the director, “How do you know that these scouts exist in the first place if you have never seen them?” It appears that we are accompanying phantom-chasers in the film.

Then a dramatic radio alert crackles on the walkie-talkie of the man we are with on patrol: one of the Arizona Border Recon reports that he sees several men wearing camouflage walking through the brush. The camera shakes as we follow the armed men running towards their objective.

And, well what do you know! What do these vigilante guys find? A group of migrants trying to enter the U.S. Imagine that! They are indeed all wearing new, cheap-looking camouflage shirts and hats, probably because they are sneaking through a desert trying to avoid the border patrol. The migrants all carry small backpacks and large bottles of water. They are, to anyone with more than a couple of braincells, obviously just desperately poor men who have risked their lives (because the drug cartels in fact prey on such men as they cross Mexico, often kidnapping them and demanding a ransom from their impoverished families back home) to try and get into the U.S. where if they succeed they will look forward to a career of underpaid, overworked labor as a landscaper, dishwasher, or house framer. These are the dastardly villains that have been apprehended by the brave men of Arizona Border Recon.

In this short scene of the film we are confronted with the whole truth of this matter. In it Mr. Foley addresses the migrants, who are now held at gunpoint by the vigilantes, in awful Spanish, “Sientate!” [Sit down!] He then asks their “coyote”, the man who they have paid to guide them across the border, a more rotund gentleman obviously a bit better off than his skinnier charges, “You speak English?” asks Foley of a foreigner.

“Yes,” replies the man in a surprisingly snarky tone for someone who is surrounded by armed paranoid fascists, “I speak English because I once worked in Cancun. You know Cancun?” As if to say, “Maybe you’ve been there on vacation, gringo? Maybe I even served you a beer once, asshole.”

Then of course Foley and his men round up the migrants and march them off to deliver them to the Border Patrol where they will all be deported back to being poor and desperate. Before they leave, the rifle-toting Foley barks to his soldiers, “If any of them touches me, drop ’em,” as if a group of unarmed, dirt poor immigrants would ever attempt such a stupid act. Our last glimpse of them is the steel door of a Border Patrol cruiser slamming shut with them inside. And there we see justice being served, damnit. Foley then tells us that the men were there, “As a re-supply to the scouts.”

There is of course not a shred of evidence to support this claim. The men looked like normal Latin American migrants trying to reach the U.S. That these men arrested by A.B.R. were part of some drug-cartel-related “scout operation” is taken as 100% true by the filmmaker for some reason. To be fair there are likely to be “scouts” in the hills above the border, but they are there to move migrants. Nowhere in the movie and in fact nowhere anywhere else is there any evidence that Mexican drug cartels are sending armed men to invade the United States across the border. There is a brief part in the beginning of the film where we hear a cut-together mix of media reports about shootings along the border and various voices from right-wing radio shows howling about how we are being invaded…but that is the normal blathering of such fools and not to be taken seriously.

In other words, it is 100% accurate to describe these men at Arizona Border Recon as completely delusional.

Let me say that again: this part of the film profiles a group of people dedicated to fighting a nonexistent enemy — they may as well be chasing flying saucers, or hunting manticores. And they have automatic weapons. And HBO, and Sundance, think they are cool. That makes me deeply pessimistic about the future of U.S. documentary film.

That the Sundance Jury could miss such a glaring contradiction speaks worlds about the continuing myopia of U.S. society and by extension U.S. independent cinema. That a group of paranoid gun-toting right-wingers in the United States who are basically just assisting the Border Patrol and who are guided by a racist delusion that all Mexicans are drug smugglers, could in any way be presented as the moral equivalent of a group of rural Mexicans self-organizing against the very real threat of narco-violence in their communities, is an unforgiveable act of ignorance on Sundance’s part and of course, by the filmmaker.

However being that Kathryn Bigelow, the Lady Macbeth of American cinema, is an executive producer of Cartel Land, I probably shouldn’t be so stunned: because if Seymour Hersh is correct in his findings about the truth of Osama Bin Laden’s killing, then Bigelow’s big-budget CIA propaganda film Zero Dark Thirty is, unsurprisingly, total horseshit.

Juxtaposing these two organizations as moral equivalents, the volunteer border patrol fascists with the autodefensas of Michoacán, is akin to comparing the Ku Klux Klan with The Deacons For Defense And Justice, the latter being an armed African-American Self-Defense force protecting people against Jim Crow violence in the 1960’s. The crucial difference is in their relation to the state: the Klan were assisting the racist Jim Crow state in oppressing blacks (and half of them were police officers so they feared no retribution), while the Deacons were defending blacks against that same racist Jim Crow state.

Just because the two groups portrayed in the film have weapons and are self-organized does not make them both causes worth supporting. An organization’s deeper politics must be examined or else the filmmaker is simply being lazy. For example The Tea Party Movement is a true grass-roots political phenomena, much as it may have been co-opted by elements of the Republican Party. However that does not mean that any sane person should support its bizarre ultraconservative agenda.

What these groups do have in common is that we could describe them all as having a politics of “populist nationalism”: they are deeply critical of their respective governments, are driven by a desire to see their countries’ populations treated more justly, and they are all made up of or appealing to regular, working people.

The crucial difference and one that Michael Moore for instance never seems to grasp is that a “regular guy” in a place that is/was the heart of a global empire is going to have a very different politics from a “regular guy” in a country that was the subject of said empire.

To put it another way, populist nationalism in a first-world, settler-colonialist society like the US is almost always going to have right-wing, pro-imperialist politics. So we see these Arizona guys dutifully acting as Border Patrol agents (the Border Patrol being one of the largest law enforcement agencies in the country), and by doing so they are effectively allying themselves with the state.

Whereas populist nationalism in a third-world, colonized society like Mexico is almost always going to be anti-imperialist, and often socialist: the autodefensas of Michoacán and elsewhere are fighting against the state, because the Mexican government, as anyone in the country will tell you, is itself in league with the drug cartels. That is why, unlike Arizona Border Recon, autodefensa groups in Mexico are often subjected to repression from the military. In fact Dr. Mireles, the organizer of the Michoacán vigilantes who is profiled in Cartel Land, has been in Mexican federal prison himself since last year. Isn’t it interesting that for all their anti-government bluster, Arizona Border Recon never face similar threats?

In fact in the film the founder of A.B.R., Tim “Nailer” Foley clearly states that originally he decided to form the group because everywhere he went to look for work in construction he found Mexican immigrants working. In other words he started the group as a blatantly racist, anti-immigrant organization. Later on, Foley says, he decided that the “real” enemy (sic) were these narcos who must be trying to stage a ground assault on the US even though there appears to be absolutely no evidence supporting this ridiculous assertion.

So we have a poor man who cannot find work, but instead of seeing the problem as being the whole system, he blames immigrants. Or else he claims that the system itself needs undocumented workers to function – which is true – but again, he takes a right-wing position and blames the victim.

Over the years, different friends of mine have brought up the question of these overwhelmingly white, gun-obsessed libertarians as potential allies with the left. Are they not disenfranchised, economically marginalized, and deeply distrustful of the government? They are. But again and again, where and when do we see them organizing? Why were they not out with us in the Black Lives Matter protests? Surely a freedom-loving, anti-government person would be supportive of a movement that opposed government-sanctioned murder, wouldn’t they?

The answer apparently is No.

And surely, since these guys in Arizona Border Recon are struggling working-class people, they could relate to a poor person like a Mexican immigrant simply trying to feed their family, couldn’t they? (Hell, even Merle Haggard saw it that way once.)

The answer apparently is No.

There are many more examples: the white anti-government libertarians howled to the rafters about what happened to the Branch Davidians in Waco in 1993, but said nothing about what happened to MOVE in Philadelphia in 1985 – and yet both groups were brutally firebombed by the police. And of course these folks flocked to support rancher Cliven Bundy in his armed standoff in Nevada, but they are absent at any of the much-larger protests against pipelines and fracking that have been sweeping the West and which have united both Indians and Cowboys, as it were. Funny how you won’t get these militia guys fighting against oil companies.

This all reminds me of a conversation I had back during that brief several-week period when it was unclear who had won the 2000 presidential election, Bush or Gore. At the time I lived in Austin and I knew a young man who hosted a conspiracy-drenched radio show and who described his politics as “neither right nor left”, which is always a sign that you are talking to a right-winger. He claimed to have connections to the various “militia” groups around the region and he told me one night, in grave tones, that were Al Gore to steal the election from George W. Bush, there would definitely follow a “revolution”, and that the militias would rise up and attempt to overthrow that would-be dictator Al Gore.

Leaving aside the foolishness of believing that a spineless milquetoast like Al Gore would ever do anything of the sort, what transpired was the complete opposite: it was of course George W. Bush who stole the election (and the ever-pathetic Democratic Party let him do it, naturally). And did the militias rise up and object to this blatantly anti-democratic move? They did not. The militias had no problem with this. And then 9-11 happened and Bush charged into an illegal war that he carried out for the most cynical of objectives. The militias apparently had no problem with this either. Following this, then-Attorney General John Ashcroft all but wiped his ass with the U.S. Constitution. The militias had no problem with this either. Because at heart, they are not “neither right nor left”, they are patriotic racist right-wingers. They may be disenfranchised, anti-government, pro-community (depends which community, however), but unless something serious changes, they remain an obstacle to progressive political change, not an asset. Or at least very rarely so.

Matthew Heineman’s film Cartel Land contains excellent footage and he deserves compliments for his dedication to that part of the craft. But he completely undermines his film’s strength with a lazy, naïve, and completely failed sense of political context for a subject matter that urgently demands it. Simply having access to armed conflict and armed men does not absolve a documentarian of the responsibility of explaining exactly what the Jesus fuck is going on when everyone starts waving rifles around.

[Full disclosure: I myself have covered several armed conflicts as a documentary filmmaker, and each time I tried to do what I have described above, and provide adequate context. The interested reader is invited to watch my work, and decide for themselves if I succeeded.]

That neither Heineman nor the Sundance jury saw the fatally obvious faults in the film’s argument speaks worlds about U.S. independent cinema and the continuing myopia of our own country towards the rest of the world, especially with regards to our “distant neighbor” directly to the south. And with blowhards like Donald Trump riding high in the presidential polls, our own homegrown American xenophobic fascism is nothing no sniff at. It’s time for all Americans, most especially documentary filmmakers, to end this self-enforced ignorance, and Cartel Land does nothing towards achieving that goal, in fact it impedes it. This film is most useful as “negative inspiration” in other words, “here is what you should not do”, otherwise it has not justified its addition to the global landfill.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.