At the entrance were three photograph collages of those who have fallen to fatal overdoses, many of them youthful and vibrant British Columbians.

It is intended to be a reminder that this scourge isn’t something confined to the back alleys of the Downtown Eastside. One B.C. presentation showed a photo of a smiling young couple from North Vancouver with their baby.

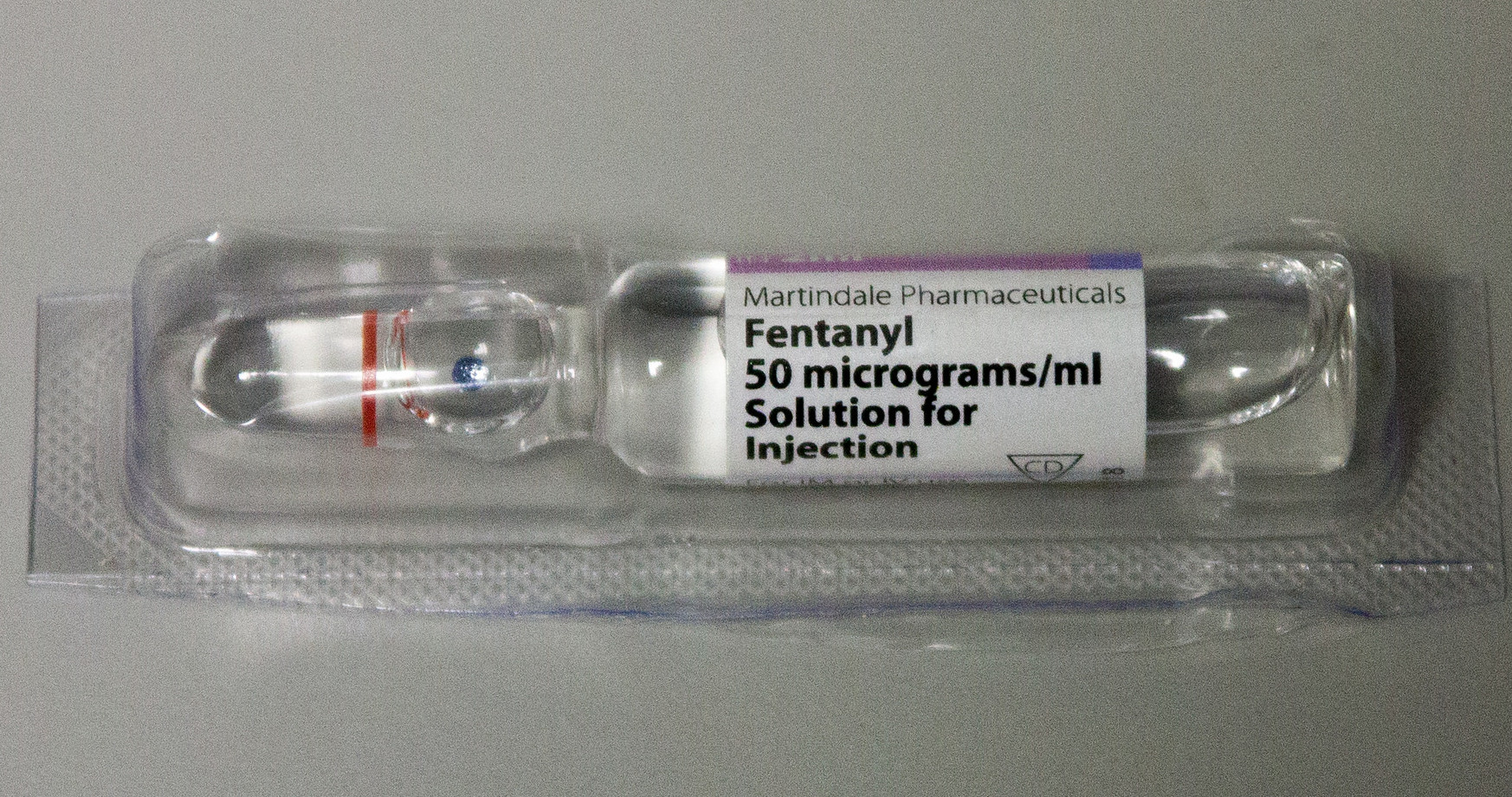

Fentanyl has been in the news a lot this past year. As the synthetic opioid reaches deeper into Canadian towns and cities, there’s a rise in reporting about overdoses.

Predictably, the majority of these stories feature “high functioning” drug users, casual users, people with stable employment, middle-class status and their tragic tales of having unwittingly, or accidentally, overdosed on fentanyl.

As fentanyl menaces “youthful and vibrant” Canadians, the news pays more attention.

It’s a classic problem with mainstream news: drug-addicted Canadians with no fixed address who overdose aren’t newsworthy. Or, they aren’t as newsworthy as drug-addicted Canadians with an address, a good job or upward social mobility.

The good news is that there is more attention on the drug crisis, and the need to broadly distribute naloxone, the antidote to an opioid overdose. In June, Ontario announced that naloxone would be available without a prescription at Ontario pharmacies.

Drug overdoses are at crisis levels. From January to October, there have been 622 apparent drug overdose deaths alone in British Columbia. This is a more than 50 per cent increase from the year prior. Overdoses related to fentanyl are climbing while other overdoses are remaining stagnant.

Doctors and front-line health workers are warning that fentanyl is creeping east. If these trends continue, 2017 will be even more deadly.

And, as fentanyl makes its way into party drugs that are consumed by groups of people together, the deaths will increasingly be in clusters, as friends or family overdose on the same batch.

The B.C. Liberals have struck a taskforce. They plan to restrict the distribution of pill presses and circulate kits for people to use to test what’s in their drugs. They are calling for more powers to be given to Canada Border Services Agency to search smaller packages.

Is more policing really the solution here? And, while a testing kit will help casual drug users with the social capital to obtain them and who can afford to ditch bad drugs if there is fentanyl detected, what good are kits if you’re already struggling to survive with a vicious addiction that won’t leave you alone?

We have to do better.

Fentanyl is good business if you’re making money off of illegal drugs. Because the drug is so potent in small quantities, it’s easy to smuggle into Canada or make, and it’s easier to make lots of money from when compared to other drugs. The illegality of the drugs fuels its power — and its ability to take people’s lives.

The federal government has done very little to address this crisis. They have made legislation to allow for more safe injection locations, a policy that was viciously opposed by the Harper Conservatives, but they’re even reluctant to call a state of emergency.

It seems like the most obvious way to combat fentanyl is to undercut what makes it so popular for dealers, and then deal with the underlying public health issues. Why not give people the tools that they need to know about where their drugs are coming from, to reduce the possibility of fentanyl sneaking into them? Isn’t now the time to talk about drug decriminalization and even legalization?

The Liberals promised to legalize marijuana. But since their election in 2015, it’s clear that the Liberals are more interested in a model that legalizes drug profits, rather than legalizes drug use.

The recent announcement that veterans who use pot will have their daily doses cut from 10g to 3g is a good example of this: sure, they’re cutting into the profits of marijuana growers, but by not encouraging people to simply grow their own, and medicalizing marijuana use, the restricted market remains in place, and medical marijuana facilities remain ready for profits.

The largest medical marijuana grower, Canopy Growth Corp., reached a peak of $17 per share in early November. Shares dropped by 15 per cent when the government announced that it would limit daily marijuana doses. Canopy estimates that the medical marijuana market will reach $10 billion annually. That is, if it remains restricted.

The CEO of Canopy Growth Corp. is Bruce Linton. A quick search of Elections Canada data shows that a Bruce Linton of Ottawa has been a regular contributor to the Liberal Party of Canada, with more than $33,000 in donations since 2005. The company’s president Mark Zekulin was senior advisor to former Ontario Liberal Finance Minister Dwight Duncan.

Indeed, even with a soft drug like pot, there’s big money to be made.

This is bad news for users of hard drugs. While Portugal’s decision to decriminalize all drugs is a potentially interesting model for Canada to follow, the federal government isn’t likely to enact policies that loosen the restrictions on drugs.

This hurts the folks whose stories are hidden from mainstream news, the most.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: Flickr/School of Veterinary Medicine and Science University of Nottingham, UK