While all eyes remain on the impending U.S. Supreme Court decision targetting abortion rights by overturning Roe v Wade, a new book is working to fill a gap in people’s understanding of abortion access north of the border.

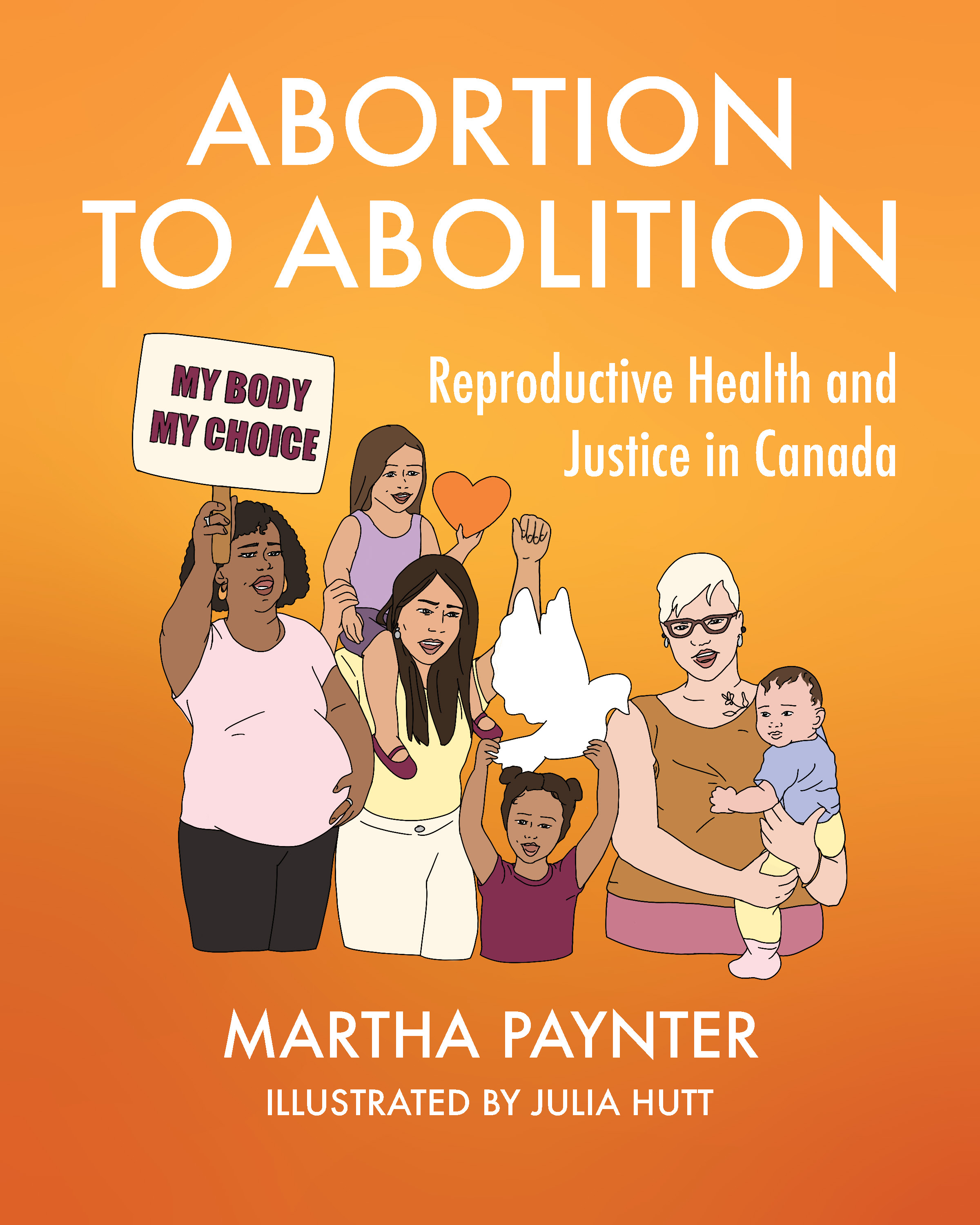

Authored by Martha Paynter, Abortion to Abolition: Reproductive Health and Justice in Canada details the intersections between parenting, bodily autonomy, and policing and the carceral system.

Panyter is uniquely positioned to pen this type of comprehensive look at reproductive justice. A registered nurse who specializes in abortion and postpartum care, she’s also the founder and chair of Wellness Within, an organization in Nova Scotia that provides support and advocacy for mothers navigating the criminal justice system. Paynter began her career in abortion care by spending her Tuesdays at Clinic 554 in New Brunswick, escorting patients into abortion care providers safely, due to crowds of anti-abortion advocates harassing patients seeking a normal medical service.

“Clinic 554 remains really our national symbol of the enduring limitations,” Paynter said in an interview with rabble.ca. “New Brunswick has always had, since 1810, the most restrictive and conservative approach to abortion access,” noting that the province’s Medical Services Payment Act prevents physicians from being paid for abortion care services if they are provided in a “free-standing” clinics.

While both medication abortions and aspiration surgical abortions are available, Paynter’s book explains that economic inequality prevents many child-bearing people from accessing the care they need.

In Nova Scotia, where Paynter is based, one-in-four children live in poverty. In fact, the rate of child poverty in the province changed by just 0.1 per cent between 1989 and 2019, the worst in the country.

Abortion to Abolition traces the reproductive justice movement to Black feminists in the United States, describing their focus on the impact of racism and limiting choice, while also considering how other layers of oppression impact choice-making.

Reprocide

One term Paynter uses in her book is reprocide: genocide through reproductive oppression. Coined by Loretta Ross, one of the founders of the reproductive rights movement, reprocide is explained by Paynter as the idea that reproduction, family planning, and decision-making of whole populations is a deliberate choice by the Canadian government. The most obvious example, she added, is Canada’s Child Protection Policy. In Canada, one in every two women in federal correctional facilities identify as Indigenous, while 52 per cent of children in the foster care system are also Indigenous.

“That is killing the family,” she said. “Making permanent the destruction of those family and community ties, which, just like the residential schools, is intending and succeeding at destroying culture.”

As Paynter explains, the average length of stay in a provincial facility in Canada is about a week. That’s enough time, she adds, to lose your job, your house, and your children.

“And once you’ve lost them, you can try for a year, year-and-a-half to get them back, depending on the jurisdiction, and you have everything stacked against you,” she said. “One week in custody can ruin many people’s lives.”

Paynter’s book also talks in-depth about the negative health care outcomes that affect separated mothers and children in the form of intergenerational trauma.

“It’s not just the physical welfare that the child can have compromised,” she said, noting children in the care of the state often face physical, emotional, and even sexual abuse in the system. “[There’s a] long term threat to their very identity and core sense of belonging and sense of worth, and that’s why we see the foster care system as a pipeline back into the prison system for the whole thing to renew itself again.”

On the subject of pregnancy in prison, Paynter noted that Canada has very little data to track violations of reproductive rights, or even the frequency of pregnancy in prisons. In the U.S., she added, only one per cent of federal prisoners had their pregnancies end in abortion, compared to the national average of more than 15 per cent.

“We are deliberately keeping ourselves in the dark about what’s happening to these people,” Paynter said, noting that babies born in prisons are more likely to be premature, which increases the likelihood of newborn death.

Putting a face to reproductive care

What makes Paynter’s series of profiles so powerful is that she’s not writing about her observations from the bleachers; she’s also documenting experiences from people she has carefully taken the time to get to know. Whether it’s through providing a prison workshop, providing reproductive care, or by researching the pioneers of the reproductive rights movement, Paynter honours the subjects of her book while giving their stories a face.

Nearly two dozen stories connecting the intersections of reproductive justice are intertwined by beautiful illustrations by artist Julia Hutt. One of the stories made headlines back in 2020 when a mother—still shopping for groceries at Walmart—was assaulted by police in front of her toddler-aged children. The alleged crime the young woman, Santina Rao, committed: not paying for items she’d yet to have the opportunity to pay for.

Rao’s story went viral after a witness recorded the assault where she was taken down by a Halifax Regional Police officer and breaking her arm in the process. Paynter pointed out that Rao’s story showed the public what the police are actually meant to protect: property. In this case, as Paynter says, a grapefruit.

“When we think about how women will have their children taken from them because those women have been beaten in front of those children by an abusive partner, CPS will come in and take your kids for that,” she explained. “Meanwhile, the police can beat your mother in front of you, because she hasn’t quite made it to the checkout yet with that grapefruit.”

That act of police brutality against Rao became a driving force behind the Defund the Police movement in Nova Scotia.

Listen to rabble radio this week to hear the full interview between Martha Paynter and Stephen Wentzell.