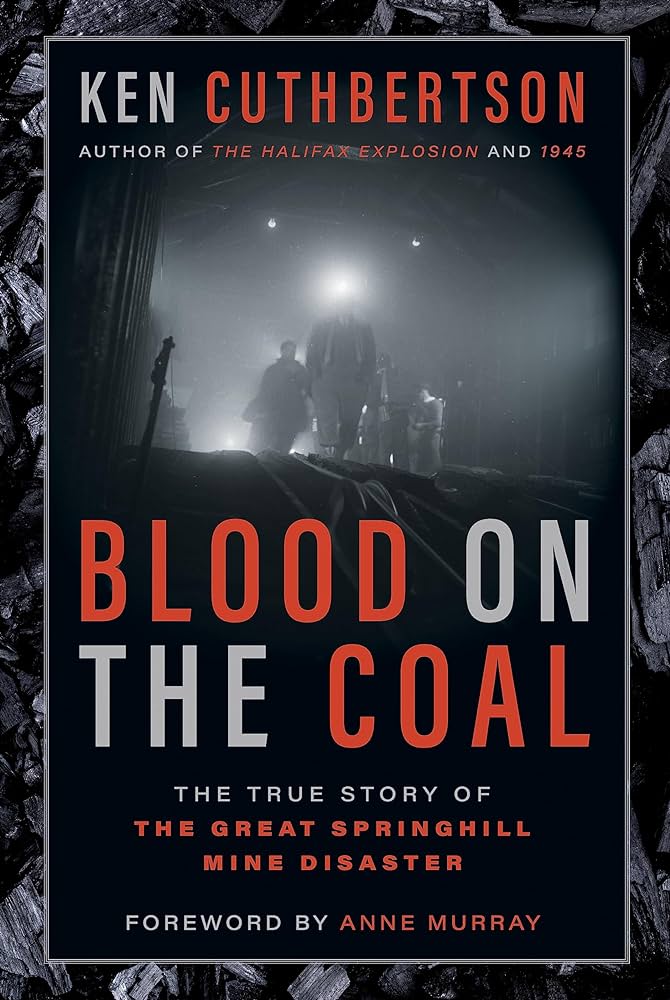

Anne Murray reminisces in the forward of a new book about growing up in Springhill, NS, the site of a horrible 1958 mining disaster at the number two colliery (a British term for a mine and surrounding building and equipment infrastructure).

She recounts how her father, one of the town doctors and her entire family, stuck around even after their one industry town lost its major employer, the British owned Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation which decided to close its money losing coal mine following what happened.

As families moved elsewhere to find work, the population of Springhill subsequently dropped from 7,000 to about 2,000. The town eventually lost its municipal status.

The singer’s own words can be found inside a compelling new historical nonfiction book by veteran Kingston author and journalist Ken Cuthbertson which is aptly titled, Blood on the Coal: The True Story of the Great Springhill Mine Disaster.

Mini-earthquakes or what locals call “bumps” are a common occurrence in this part of the world. More than 500 bumps had shaken the Springhill mine in the four decades prior to what happened in 1958.

This time around on October 23, the upheaval in the ground was deadly, resulting in the collapse of the underground structure at the number 2 colliery which was extremely deep at 4,600 feet and thus both dangerous and unstable, says Cuthbertson.

One hundred and seventy-four men (in an all-male profession) were in the mine that day when disaster struck. Some of the miners were trapped and had to wait for a rescue. Scores were injured and 75 lost their lives.

Cuthbertson recounts a long history of coal mining in Springhill going back to the 1880s when the town was the largest producer of coal in Canada.

In the late 1950s, there was less regulatory attention paid to working conditions or safety gear to boot. Daily on the job, each miner dressed casually in pants and tee shirts and wore head lamps. Underground they experienced sheer darkness, confined space, smell, rats, coal dust, noxious gases (known as fire damp) and methane (which is flammable). Many miners ended up getting the potentially deadly black lung disease which results from the penetration of the coal dust into the lungs and the development of serious breathing problems.

Miners’ pay consisted of how much coal they extracted each day; there was no regular salary. So, when the disaster happened, it was no coal, no money for the miners and their economically dependent large families.

One piece of good news was that the employer was legally obligated to pay survivors’ benefit cheques for widows of the miners killed on the job.

The Springhill mine disaster garnered a lot of international attention. A moving folk song, the Ballad of Springhill was written and performed by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger in the UK. Furthermore, two of the surviving Springhill miners travelled to New York City to appear on the Ed Sullivan TV show, which had a loyal Canadian audience (including myself as a young lad).

A larger number of Springhill miners and their families were also invited by the state of Georgia to enjoy an all-expenses paid week-long vacation at the Jekyll Island State Park as part of a tourism gambit. State officials overseeing a strict Jim Crow regime of segregated barriers for their black residents were embarrassed to discover that one of the invited Springhill miners Maurice Ruddick (also known as the ‘Singing Miner’) happened to be a Black Afro-Nova Scotian. But by then it was too late for the state to rescind the invitation.

The working conditions in the mining sector as described in Blood on the Coal are not of the same magnitude today. Nevertheless, going over Cuthbertson’s book I am reminded of the scholarly writings of Harold Innis and his analysis of the reliance on resources or staples for economic survival and advancement in Canada in its evolution as a settler colonial state.

The destructive 2016 wildfire in Fort McMurray and the denial in the city and across Alberta politically of the role that fossil fuels and the tar sands played in the intensity and scope of the mishap does remind me of a similar phenomenon and attitude which happened in Springhill in 1958.

Cuthbertson told me in an interview that there was a visceral dislike in Springhill in 1958 for big city journalists and photographers arriving in town in their suits to cover the mining disaster. Their appearance represented for the locals the end of their livelihood in King Coal. Indeed, the men recovering from the disaster were quite prepared to return to the mine once it was fixed up. Their fears were correct as it was subsequently closed down and the structures demolished.

What keeps people going in the most awful of environmental conditions is a work and social culture which in Springhill, NS spanned generations.