In her youth, Christina McCall dreamed of becoming a theatre critic, where she could hobnob in the theatre districts of London or New York. Instead, she crafted a career as a magazine writer, immersing herself in the drama of the Canadian political stage.

Though she might best be remembered for her in-depth coverage of the Liberal Party of Canada, McCall’s breadth included issues of urban planning, Canadian nationalism, and of course, feminism.

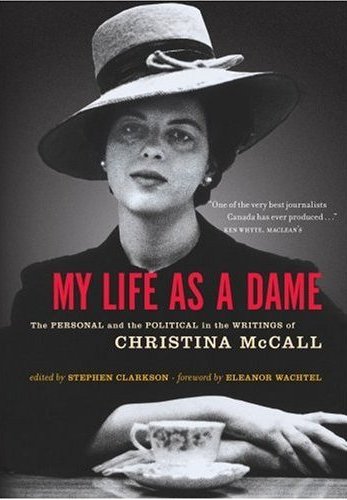

McCall passed away in 2005, leaving behind an unfinished autobiography coupled with decades of published writing in magazines such as Maclean’s, Chatelaine and Saturday Night. Selections of her writing have been compiled and edited by her husband, Stephen Clarkson, resulting in My Life as a Dame: The Personal and the Political in the Writings of Christina McCall.

Christina McCall began her career in 1956, shortly after graduating from the University of Toronto’s prestigious Victoria College. Here, McCall’s "steely-eyed but compassionate feminism," as Clarkson later called it, separated her from her classmates, who she viewed as "good girls with shiny hair and diamond engagement rings," who were housewives in waiting. McCall envisioned a world where women didn’t view a "marriage license as a lifetime meal ticket," but she saw little to prove this was possible.

So, she began her career like many young women did in the 1950s — pouring coffee for her male counterparts. Editorial secretaries at Maclean’s were the "lowliest wage slaves" in an industry that was wickedly misogynistic.

But McCall didn’t stay at the bottom for long. In 1957, she published her first feature for the magazine, a profile on female mining pioneer, Viola MacMillan, which her superiors accepted without revision. At only 22, McCall was on her way to becoming one of the most recognized writers in the country.

For those familiar with McCall’s writing, My Life as a Dame is a collection of some of her most memorable work. For those who have yet to experience her witty, yet fiercely intelligent prose, the book is an introduction to McCall as a journalist, social historian, nationalist, feminist and "the best political writer in Canada," according to Ken Whyte.

Divided into four parts, My Life as a Dame begins with the first two chapters of McCall’s unfinished memoirs, which are also the last pages she wrote before her death. The apt title of the unpublished book, also My Life as a Dame, was an ode to female journalists who were often dismissed as "dumb broads" capable only of writing articles on softer issues, such as fashion.

The second part, "Canadian Society: The Low and the High," reveals McCall’s talent for accurately capturing the mood of her subjects, whether she is writing of a dismal town, faltering in the aftermath of a mine disaster, or writing a colourful portrait of urbanist Jane Jacobs. Not surprisingly, many of the timeless issues McCall wrote about, such as urban sprawl and classism, still face Canadian cities today, decades later.

"Feminist in Arms," part three of this anthology, shows Christina McCall’s prescience as a feminist at a time when very few writers in the mainstream press were writing about the women’s movement. An ardent advocate of The Royal Commission on the Status of Women, McCall wrote of her disappointment of the "formidably bleak and awkward document," which she wrote was "so lacking in passion that it might be a report on freight rates." McCall was moved by the personal stories of women who gave their testimonies to the commission, regretting that the final report did not give them enough of a voice.

My Life as a Dame showcases McCall’s ability to masterfully weave together personal journalism and social commentary, especially when discussing women’s issues. For example, in her essay "Some Awkward Truths the Royal Commission Missed," she manages to seamlessly transition between the serious topic of the Royal Commission hearings and a recent lunch-line conversation about homemaking. In one particularly memorable article, she alludes to her own experience with "separation syndrome" just as she was divorcing her first husband, Peter C. Newman.

Even when writing on topics generally left for the "second sex," McCall approached these assignments as though she was uncovering a telling social trend. "She wrote about style not as a maven of fashion but as a sociologist who could understand symptomatic value as a signal of a culture’s every-changing mores," writes Clarkson.

Finally, part four highlights McCall’s essays on Canadian politics, focusing on four major themes: The Pearson years, Canadian nationalism, Quebec and the Trudeau era. Along with her in depth political analysis written for magazines and newspapers, McCall also wrote a number of books, including Grits: An Intimate Portrait of the Liberal Party and two volumes of Trudeau and Our Times, co-written by Clarkson.

Though some might argue that equality for female journalists isn’t quite there yet, My Life as a Dame sheds insight on a time when female journalists were mere tokens in a male-dominated industry. In an essay called "What Won’t Appear in my Next Paradise," which acts as an endnote to this book, McCall prophesized about the year 2020, dreaming of "a society in which women aren’t and don’t feel like an oppressed minority, a society in which they are truly equal to men. But not, of course, the same."

While society might not be quite there yet, one thing is for sure — Christina McCall’s concoction of pithy literary non-fiction was a major step forward for Canadian women and Canadian journalism, making My Life as a Dame a critical, yet heartwarming read.–Jessica Rose

Jessica Rose is a regular contributor to rabble’s book lounge.