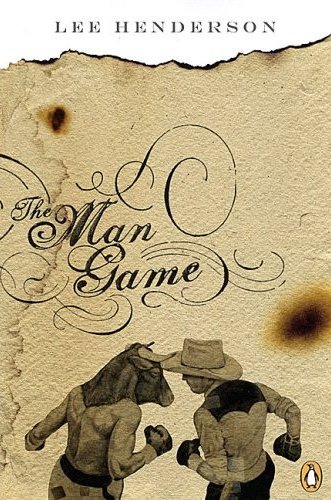

“Whenever I see sculptures by David Altmejd, who is from Montreal, I think of Vancouver — a decapitated rotting werewolf head bursting with crystals,” writes author Lee Henderson by email, answering a question about the frontier-era city portrait that he’s painted in his masterful first novel The Man Game. “The crystal castles of Vancouver are signs of the decomposition of the beast we once were.”

The werewolf-crystals are raised in answer to my question as to how the balls-of-steel Old West resource town depicted in Henderson’s book — in which sinewy and stink-crusty ex-loggers perform an underground combat sport called “the man game” — evolved into today’s sissified capital of yoga pants and tiny dogs in sweaters. But the book itself is the answer to the question: as much as it’s a stirring Western, The Man Game is also a Jungian essay that finds and explores the hard kernel of femininity at the core of masculinity and vice versa. Whenever Henderson’s male characters are at their butchest, they’re working from a place of wounded helplessness, dependence and poverty. The blood-sport man game is, in fact, part ballroom dance, laden with special moves and partnered steps, a burlesque of machismo whose progenitor, kept secret from the game’s fans, is a woman — herself the young city’s epitome of feminine beauty.

The young woman is Molly Erwagen, a former Vaudevillian and wife of a paralyzed accountant (how’s that for the obverse of proletarian macho?), who first approaches the city on the day of the infamous Vancouver Fire of 1886. At her arrival and soon again afterwards, Molly is witness to brawls involving the woodsmen Pisk and Litz, the men suspected of having set the town ablaze. Tracking them down (through her Squamish Indian ward, Toronto, one of the great sleeper characters of recent Canadian fiction) and enlisting them to be coached in the man game, she creates a theatrical sporting phenomenon that enraptures the men of the city. Like the Chinook jargon spoken amongst the city-dwellers (an actual creole hybrid of aboriginal, European and Asian languages once used on the West Coast and sprinkled throughout Henderson’s text), the man game becomes a shared vernacular actively constructed by the people who share it — Litz and Pisk’s enemies increasingly channel their raw hostility and animosity into the codified and ritualized violence of the sport, and the result is unintentionally civilizing.

In this sense — the way it transforms brute violence into something sophisticated and comprehensible — the sport is an apt metaphor for what happens as frontier outposts crystallize into new civilizations; it’s what some political scientists call the substitution of antagonism with agonism; the replacement of out-and-out conflict with regulated, adversarial but ultimately civil engagement.

Appropriately, then, the climactic round of the man game occurs in competition with an anti-Asian race riot in 1887. Vancouver’s founding populist violence against Chinese labourers was the precise reverse of the process of boiling down raw conflict into rational civic discourse — instead, it was the channelling of rational social complaint (against the poor working conditions and low wages consciously brought about by the city’s white business elite) into primal, inchoate racist violence.

“Racism is Vancouver’s history. That’s how I saw it,” says Henderson. “Not separate from Vancouver’s story, not an incident within it, racism is the identity.” Tellingly, the crowds cheering (and betting) on the man game are the only space in the story where Asian and European Vancouverites intermingle, besides the popular Chinese bakery that just barely survives the fire, and which provides Toronto with his favourite pastries as well as an opportunity for heroic redemption.

The Man Game is a literary gem, studded with similes akin to the werewolf-crystals: weird and absolutely pitch-perfect (one man game loser, for example, “[f]elt like he was rolling the losing numbers to the lottery around inside his head”). It’s hard to overstate just how funny, sharp, entertaining and intelligent a book Henderson has wrought here. And while the book is certain to engage those outside of the 604 area code, Vancouverites especially will thrill to just how much they recognize in the 1880s edition of the city, from the sushi to the drugs. Henderson: “Yes, we’re like every other city, fucked up, and so very much the same as we were in 1886.”–Charles Demers

Charles Demers is a Vancouver-based activist, comedian and television host, and is author of the forthcoming novel, The Prescription Errors, and book of essays, Vancouver Special.