Despite the current unsustainability of our individual carbon footprints, the standard method of personal renewal in affluent postmodern society continues to be tourism. Eyes glazed over by routine and sameness are opened to the pseudo-newness of “elsewhere.” It’s a strategy often used in the creative writing game. From that temporary, distant perspective, one can cast a long look back at one’s homeland, and gain fresh insights.

However, there are those citizens of Canada (and of any of the affluent postmodern societies) who for no other reason than the colour of their skin, their sexual orientation, religious or philosophical or political beliefs, find that “at home they’re tourists” (to paraphrase Gang of Four). While many will concern themselves with assimilation, others — and the poet Kaie Kellough is one such — bring their consciousness to bear on their situation, and offer up new perspectives on citizenship.

Kellough, originally a Westerner with roots in Calgary and Vancouver, moved to Montreal in 1998. From the start, he has carved a unique niche for himself in the African diasporic arts community. He self-published numerous chapbooks, and his first book of poetry, Lettricity, appeared in 2004. He also co-edited (with Jason Selman) 2006’s essential anthology talking book: blues, jazz, dub, rap, song and freedom in the literature and orature of Montreal’s Kalmunity Vibe Collective.

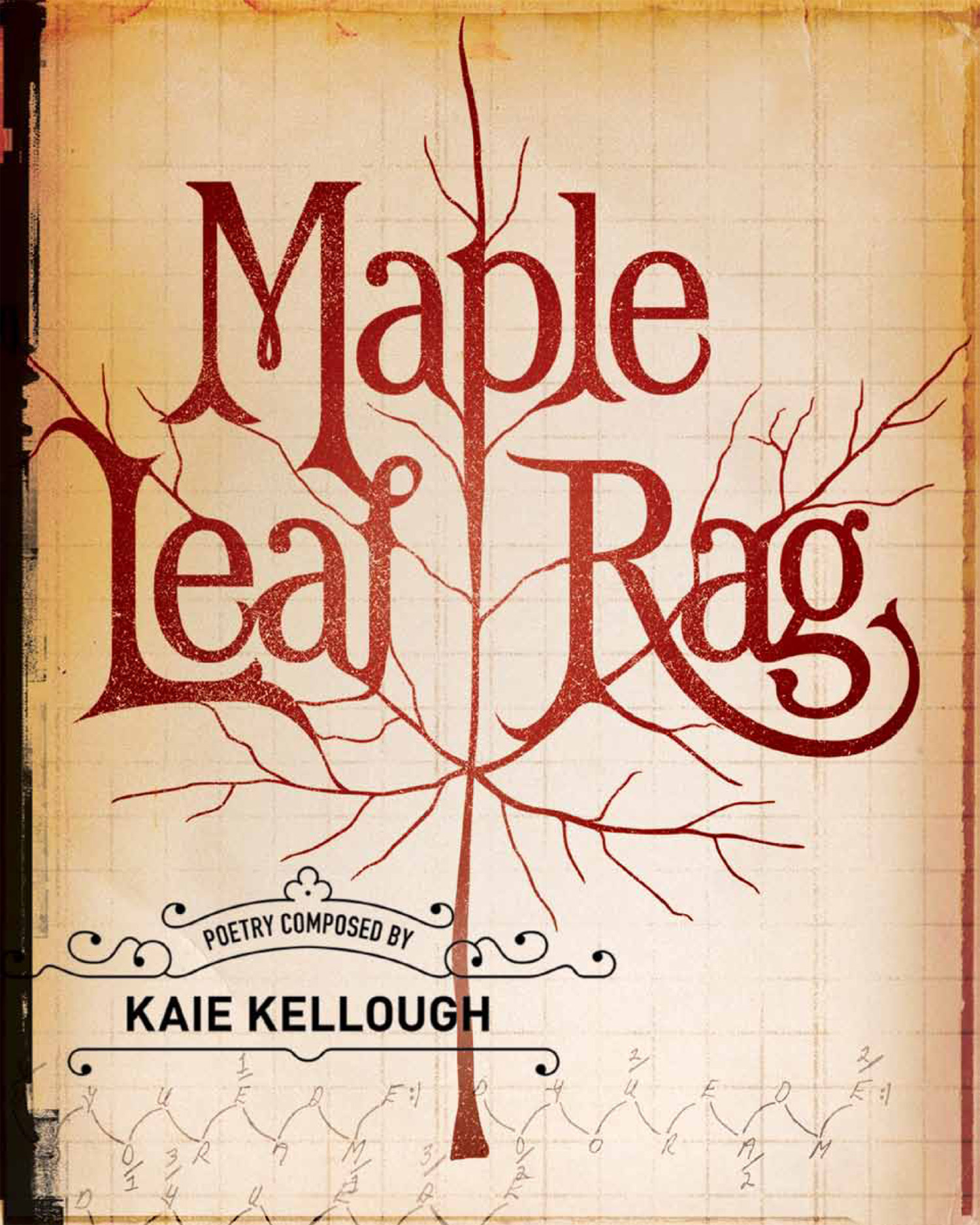

Kellough’s page poetry has always exhibited a joyful engagement with wordplay, and this is highlighted in many of the poems in his new collection, Maple Leaf Rag. Poems like “boy hood dub II,” “jelly roll in canaan land” and “échos” incorporate elements of concrete poetry to draw out the inherent sound of the work; others, like “word sound system #2,” “quittin’ rhyme” and “the didnt dues” foreground the underlying jazz-inflected voice of each piece by using Maple Leaf Rag‘s design for the artful distribution of words across large-format pages. As Kellough writes in his introduction, “sound guides each poem, often to a place where words are splintered, meanderings belabored, & meanings blurred.”

In a recent interview I did with Kellough, he expressed some doubts about the more narrative poems in his oeuvre. I hope this is just a side-effect of his current enthusiasm for sound and concrete poetry, and not a hard-and-fast judgement, because some of my favourite Kellough pieces are his prose-poetry meditations on the particularities and peculiarities of various quartiers in Montreal. “between the royal mount and the river below” paints a portrait of Hochelaga-Maisonneuve that is as accurate and poignant as anything I’ve read on this city:

children tough and wiry as weeds dash down rusted walkups, kick away cans and garbage bags to clear a canvas, chalk daydreams on the sidewalk, stooped men wither into cigarette smoke, all the pawnshops on ontario est are packed with hagglers hawking bile and costume jewelry for petty prices — neighbourhood princes seeking oblivion in bomb-shaped 1l bottles of bière extra-forte, once drunk, will they dream of cartier’s voyages?

Although not conceived as a unified, thematic collection, I found Maple Leaf Rag‘s overall impact to be like a rollicking guided tour of an “other” Canada, a black diasporic, jazzy-bluesy rumination on notions of place and identity in this 21st century. Whether commenting on encounters of racism in Calgary schoolyards or delivering brief lessons on the secret history of Canadian Blacks in B.C., Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia, or ruminating on farther-flung locales like Harlem, New Orleans and the U.K., Kellough’s poems remain rooted in personal experience, with a voice that’s sometimes acerbic, often ironic, occasionally angry, but always compassionate, a voice which carries a high level of commitment to the craft of the poet.—Vincent Tinguely

Vince Tinguely is a Montreal-based performance poet. Read his blog illimitable reality wreck.