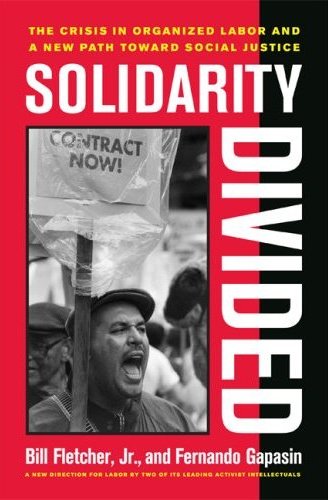

Author, educator and union activist, Bill Fletcher, Jr., was the keynote speaker for a conference entitled Globalization, Union Renewal and the Fight for Social Justice at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education in Toronto last month. The event was sponsored by the Labour Education Centre. Fletcher, formerly the president of TransAfrica Forum, is co-author (with Fernando Gapasin) of the recently released book, Solidarity Divided: The Crisis in Organized Labor and a New Path Toward Social Justice. The book is a candid appraisal of the U.S. trade union movement that draws deep lessons from history while constructively critiquing the present.

Robin Breon met up with Fletcher for this exclusive interview for rabble.ca readers.

RB: One central thesis of the book is the pivotal role that central labour councils (herein referred to as CLCs and not to be confused with the Canadian Labour Congress – ed.) can play with regard to organizing and focusing the work of local unions in predominantly urban arenas. You comment on "missed opportunities" with regard to the role of CLCs and I was wondering if you could expand on that a bit?

BF: One of the missed opportunities we refer to in the book is the notion of geographic organizing to increase union density in urban areas. The problem occurs when local affiliates within the central labour councils refuse to support the strategies being put forth by the CLC. This can occur for a number of reasons. It might be that organizing the unorganized is seen as central to the union project by some locals while others may feel that it is just some kind of "add on" burden that takes away from the day to day contract servicing that they see as their main responsibility to their members. After all, the geographic approach to organizing in urban areas comes out of the AFL-CIO’s Union Cities program that asks CLCs to envision organizing from one end of the city to the other rather than just individual workplaces. This is a daunting challenge.

Another missed opportunity by the CLCs was to transform them into councils of workers rather than a coalition of affiliated unions. Although this discussion never got off the ground under the Sweeney administration at the AFL-CIO, it did gain some credence in New York City when the NYC Labor Council invited in the New York Taxi Cab Alliance that, although it was not a bona fide union per se, had many of the common interests and concerns that the affiliated unions had.

RB: With regard to organizing, when there is a jurisdictional question, how should that be handled among the stakeholders within any particular CLC?

BF: One approach we suggested was that when interest is expressed by a group of workers or when a strategic plan is completed that outlines a particular geographic area that is to be organized, then the various affiliates should all pull their resources and participate according to their abilities in the organizing drive. If the drive proves to be successful, then a jurisdictional decision should be made within the CLC that basically involves all of the stakeholders who participated in the effort. If one particular union is seen as more appropriate than another, then so be it. The next successful effort could see members going into another union and so on and so forth until new members are joined up with appropriate affiliates within the CLC. Everyone should benefit over the long run.

RB: The book speaks about the union movement’s reluctance and sometimes outright unwillingness to go out and organize the unorganized and you say there is a danger in "ideologizing" the question of organizing. Could you explain that a bit more?

BF: What we are trying to get at here is that the idea of union organizing in and of itself is not necessarily a progressive idea all the time. Though workers are generally better off being in unions than not, it can also be a power grab that is retrogressive. For example, a union leader may be keen on organizing within his particular sector because he wants to build a power base within a union that has historically discriminated against women and people of color. There is nothing within the strategic plan or public position of this particular union leader that indicates he has any problem with this. But we have a problem with a union leader that would seek to build an organization that has historically discriminated against people. There is nothing progressive in organizing and increasing membership within this kind of model. This is what we mean by ideologizing the question of organizing. You must look closely at what kind of organization you are asking people to join.

RB: On the question of "core jurisdictions" – it seems to me that this genie has been out of the bottle for some time now what with Teamsters organizing airline pilots, while the Autoworkers organize the flight attendants and Steelworkers organize university administrative and technical staff. I don’t necessarily have a problem with this in that I work as a university administrator and we are getting excellent representation from the Steelworkers. But it does seem to speak to the issues that you raise in your book, am I correct in this assumption?

BF: The lack of core jurisdictions within the union movement is problematic on several levels. First of all it tends to facilitate mergers and amalgamations more than it does broader organizing activities. And the advent of amalgamated unions has in some cases been just a move to keep their membership numbers up. This is not unlike the private sector that links a weaker partner (one with liabilities, debts, etc.) up with a stronger partner so that it looks good on paper but doesn’t necessarily translate into the possibility of expansion. Steel and Auto especially will have to come up with new organizing strategies in the manufacturing sector or they will simply continue to absorb smaller unions.

RB: You use the term "social justice unionism" in the book. With the election of Barack Obama, do you think this concept has a better chance of catching on and in what areas do you see movement is possible?

BF: The idea of social justice unionism is a concept that you know well in Canada. We have to move unions in the States to take an interest in and be part of the movement to bring about a national health care program, to take on issues such as poverty, affordable housing and education. I think more than the recent election, the most compelling reason that union members will see social justice unionism as a viable project is because of the economic meltdown. It was this crisis, more than anything else that allowed the Obama victory to happen.

RB: In your view, what is labour’s top priority for the new administration in Washington?

BF: Passing the Employee Free Choice Act is certainly one top priority. This legislation would bring in card check and allow unions to organize more freely and effectively without so much company/management interference and intimidation during the process. But I think also that labour’s agenda needs to be much broader than it has been in the past with a re-defining and expansion of the notions of what constitutes the working class. We need to take on the rebuilding of the nation’s infrastructure through major work projects and this should be part of a whole new concept of structural reforms that involves health care, education, etc.

RB: Thanks very much for this, Bill.

BF: My pleasure.

Robin Breon is vice president of USW Local 1998, University of Toronto.