When Toronto resident Ahmad El Maati refused to sign a false “confession” in a Syrian torture chamber, he was threatened with having his eyes burned out with cigarettes. Having already endured almost two months of indescribable torture, El Maati made a decision

whereby he traded his innocence for his eyes.

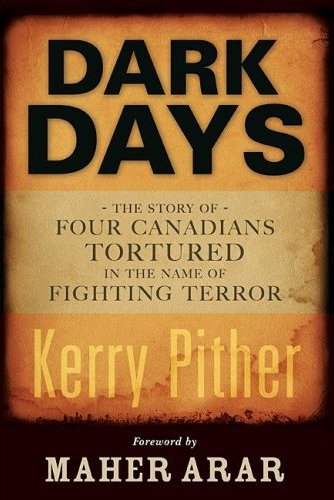

This singular act of barbarity, one of many described in Kerry Pither’s important new book Dark Days, might leave some readers feeling blessed that ours is not a country connected to torture. But anyone who reads this history of four Canadians tortured overseas with the complicity of their own government will no longer have cause for such complacent conclusions.

These four men — Maher Arar, Abdullah Almalki, Ahmad Elmaati, and Muayyed Nureddin – are all Canadian citizens who were illegally detained, interrogated and tortured in Syria and, in one case, Egypt. In all of their cases, the fingerprints of Canadian officials show up everywhere, from the torture chamber questions that could only have originated in Canada to very specific acts, originating in Ottawa, that gave the green light to those holding the overseas whips and electrical prods.

Mr. Arar’s case helped open the world’s eyes to the U.S. practice of “extraordinary rendition” (kidnapping and forced removal to overseas torture). A Canadian inquiry concluded Arar was tortured in Syria based on completely untruthful allegations that originated in Canada. He was cleared of any suspicion, and won significant compensation, though he lives with the scars of a year in a grave-like cell and physical and mental torture.

And while Time‘s Canadian edition made Arar its 2003 man of the year, fewer people are familiar with the cases of Almalki, El Maati and Nureddin, in large part because the inquiry looking into their cases was held in complete secrecy, absent the men, their lawyers, the media and the public. That inquiry, chaired by former Supreme Court judge Frank Iacobucci, did produce conclusions in October that were enough to clear the names of the men, and also found that certain “deficiencies” in governmental conduct led “indirectly” to the torture of these men.

Such cowardly ambiguity has allowed the Harper government to thusfar refuse an apology and compensation, not to mention consideration that some officials should be held accountable through the legal system.

Which is why Pither’s book is so timely. Connecting the dots going back a decade, providing a chronological overview of the political and security context in which key Canadian decisions were made to target these men and their families, Dark Days does a valuable service by recording in open view a history that the federal government is desperate to sweep under the rug.

It is a history that gives the lie to the idea that complicity was “indirect.” Indeed, how indirect is the fact that in December 2003, Muayyed Nureddin was detained by Syrian officials on his way home from an overseas trip? After being told he would never see the sun again, while being tortured, he was asked the exact same questions that were the subject of a Toronto airport interrogation three months earlier.

How “indirect” is the fact that Canadian officials sent questions to Syria regarding Mr. Almalki even though they knew this would likely result in his being tortured? Or that when he was finally released, Almalki was informed: “The Canadians are not happy that you are released, and they want you back in jail.”

Drawing largely on the public documents made available during the Arar inquiry, as well as interviews with the four men, human rights advocates, government officials and reporters who covered the stories as they developed, Dark Days is clearly an indictment of a government that had very clear choices to make about whether or not it would subscribe to the rule of law. Indeed, Pither’s book is a necessary rejoinder to the federal government’s insistence that such difficult “fog of war” decisions were made in a time of fear and anxiety following the events of Sept. 11, 2001.

Rather, Pither’s book shows that there is a clear pattern of Canadian complicity in torture, one that does not end with these cases, but which instead opens up new questions about cases like those of Algerian refugee Benamar Benatta. Benatta was Canada’s first 9/11 rendition to torture, unceremoniously kicked across the Canadian border on 9/12 as a Muslim who knew something about airplanes, leading to five years of detention and treatment amounting to torture. Benatta applied for standing at the Iacobucci inquiry but was denied.

Then there’s the case of Abousfian Abdelrazik, a Montrealer detained in Sudan five years ago at the request of CSIS, tortured and still stranded, unable to get home because Ottawa has done nothing to remove him from a no-fly list.

Dark Days is also important because it is clear on many things, not least of which is the fact that these men were tortured. Despite that fact, it is something which the Iacobucci Inquiry shamefully attempted to downplay. Indeed, a “Commissioner’s Statement” that opens the report continues to cast an air of suspicion over the men, freely repeating the word “terrorism” but not once mentioning the other T-word, Torture.

While Dark Days is well-documented and hefty, it is a fairly fast and accessible read. It could have benefitted from a more careful case of proofreading (a deficiency likely to be corrected in paperback form). More importantly, though, it could also have used a bit more background exploring how Canada’s role as torture enabler did not begin in the post-9/11 world, but has roots that go far back in this country’s history.

Examples include Canada’s first extraordinary rendition program (the kidnapping, forced disappearance and torture of First Nations children through the residential school system), its post-WWII role in developing new forms of torture (as documented in Alfred McCoy’s A Question of Torture), and Ottawa’s shameful complicity in the horrors of Vietnam, Chile, El Salvador, South Africa, Indonesia and other states where human rights atrocities were committed.

Strangely enough, Dark Days is also a hopeful work. That these men, having been targetted by the Canadian government, still have the courage and strength to speak out so that such crimes will never happen to anyone else, is a testament to the fact that the goal of torture – the complete destruction of the human person — was no match for the faith of innocent people who, despite the inestimable damage done, consider themselves “the lucky ones,” for they got out and got home.

Pither’s tome reminds one of Hannah Arendt’s famous finding of the Nazis’ “banality of evil,” the emotionless manner in which horrific policies to destroy human beings can be carried out by a bureaucracy wholly disconnected from the repercussions of their actions and decisions. While Arendt’s findings focused on the Third Reich, Pither’s recounting of decisions made within the offices of the Canadian Justice Department, CSIS, the RCMP and the foreign affairs bureaucracy, should give pause to those who wonder about the relative health of Canadian democracy.–Matthew Behrens

Matthew Behrens is a Toronto writer and editor.