(Full disclosure: Monique Bégin and Libby Davies are friends I hold dear, while Beverley McLachlin is someone I have met, and talked with on several occasions).

Early in Truth be Told: My Journey Through Life and the Law (Simon & Schuster), Beverley McLachlin writes of her homeroom teacher taking her aside to discuss the aptitude test she and her grade school classmates had recently taken. The teacher found McLachlin’s results disconcerting. She should never choose to be a telephone operator or a waitress — McLachlin had the lowest alertness scores the teacher had ever seen.

While the Grade 8 student did have very high reading-retention results, “that will not do you any good … being a girl,” the teacher explained.

Some decades later, having arrived in Ottawa, and being shown by her predecessor the office she would now occupy at the Supreme Court of Canada, McLachlin asked if judges read in their entirety each of the many books of trial evidence they received before each case (as the outgoing judge explained how well suited the closets in this particular office were to store them). He remarked that Supreme Court justices had in common at least one thing: high reading-retention.

With a gift for irony, and a fine sense of the unexpected, and unusual occurrences, McLachlin has turned her judicial writing skills into a fine memoir.

The former chief justice tells of growing up in the area around Pincher Creek in Southern Alberta, where failing family fortunes led to a series of moves to homes increasingly distant from town. Each had no running water or electricity.

Few would have expected to see a Supreme Court chief justice become a Canadian hero, but the way the McLachlin court overruled the social conservative legislative agenda being force fed through Parliament by the Harper majority government endeared her to many.

Though she does not write about it in this memoir, it was the McLachlin court that recognized that freedom of association under the charter guaranteed the right to collective bargaining, rejecting decades of anti-union Supreme Court rulings.

The judicial story concludes in Vancouver with a recently retired McLachlin riding a bus. Not far from an original safe injection site — protected by her court from attempts by the Harper government to shut it down — a man sits down beside her. He turns his head sideways: “Aren’t you that judge?” Yes, she acknowledges.

“I just want to thank you for all you did for Canada,” he says.

Any one of a great number of Vancouver bus riders could have offered a similar thank you to Libby Davies whose political memoir Outside In: A Political Memoir (Between the Lines) includes a full account of her 20-year fight to save the lives of thousands of heroin addicts dying on city streets, because the police, civic, provincial and federal authorities were too thick to understand that drug addiction was a medical problem, not a criminal matter.

Davies superbly balanced work (she took a course at UBC on memoir writing when she retired as the member of Parliament for Vancouver East, and it shows) provides numerous lessons from real life on how to make a difference as a social justice activist, working with street people from a store front, sitting on city council, or as deputy leader of the federal NDP.

Davies was a close associate of Jack Layton, and here she gives an engrossing account of the rise, and fall of NDP fortunes in the Layton years.

For many, the very personal stories Davies chooses to share with her readers will be the most interesting part of this highly readable, enjoyable book.

Like a very few other politicians (the late Marion Dewar, a former NDP MP and Ottawa mayor comes to mind) Davies was not just appreciated or admired, she was loved by her constituents.

Another elected political figure also loved by the public is Monique Bégin. In Ladies, Upstairs! My Life in Politics and After (McGill-Queen’s) she gives an engaging account of her full life, from an incredible June 1940 childhood escape from Paris (partially by foot, at the age of four, with her parents and siblings) in advance of Nazis troops, to her resuming a formal university career as chair of women’s studies, dean, and professor at the University of Ottawa.

Bégin, a sociologist, with a gift for observing, understanding, and relating the inner workings of government in our society, interrupted her graduate studies to become research director for the Royal Commission on the Status of Women. Elected to Parliament in 1972 and the first woman to claim a seat in Quebec, Bégin would serve until 1984, leaving public life as one of the most successful cabinet ministers in Canadian history.

It was as minister of health and welfare in the Pierre Trudeau government that Bégin secured the first child tax benefit paid to women (a refundable tax credit, meaning it could be even claimed by women with no income), introduced the guaranteed income supplement to take seniors out of poverty, and secured passage of the Canada Health Act. How these accomplishments, and other amazing incidents played out is what drives her fascinating narrative.

Bégin stands in the first rank of Canadian feminists, and her memoir is an indispensable primary source for anyone interested in knowing how power can be used to displace barriers the male patriarchy builds to contain Canadian women. Readers hoping to glean her secrets about how to achieve feminist change in a male-dominated milieu will not be disappointed.

Whether you want something engaging to read over the holidays, or are looking for a gift idea, or simply to satisfy your curiosity about how things happen in public life, I can recommend these three fine books by three remarkable Canadian authors.

Duncan Cameron is president emeritus of rabble.ca and writes a weekly column on politics and current affairs.

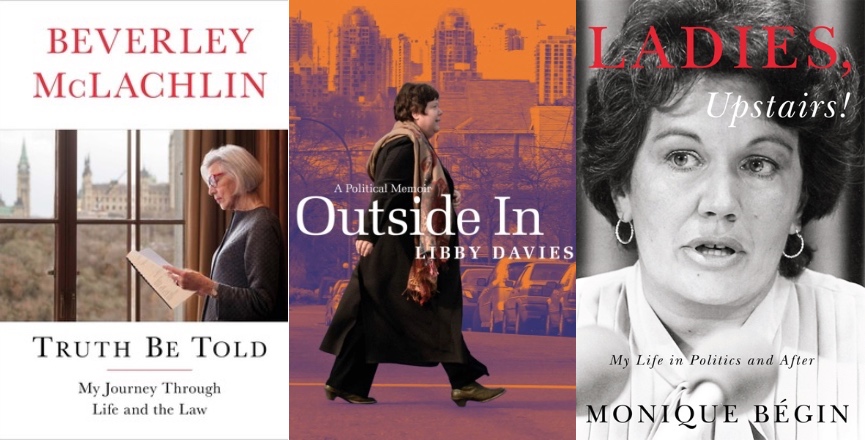

Image: Beverley McLachlin; Libby Davies; Monique Bégin