The health emergency created by the COVID-19 pandemic is of course the primary concern of Canadians, and the first priority for government to address. But it is increasingly clear that the economic fallout from the pandemic is also going to constitute an emergency. And it requires government to respond as urgently and powerfully in the economic sphere, as they are attempting for public health.

I was invited onto CBC Radio’s special broadcast today to discuss the economic consequences of the pandemic, and needed policy responses — and also to comment on the policy announcements made by Finance Minister Morneau, Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz, and superintendent of financial institutions Jeremy Rudin at a special joint news conference.

Here are some quick thoughts on what we can expect in coming months, the nature and dimensions of the policy response, and — of course — how we pay for it!

What we’re in for

There is no doubt that the macroeconomy, already near-stagnant at the end of 2019, will now slide into recession. The immediate spillover effects of cancelled transportation, cancelled tourism and entertainment events and services, and reduced output in many different industries are knocking GDP backward right now. Second-order effects will be experienced across a wide swath of the economy, as both consumers and businesses scale back their purchases dramatically. Even a short-term surge in purchases of groceries and essentials (including toilet paper!) won’t offset that shock decline in aggregate demand.

Another category of impacts will be felt through disrupted supply chains. Imported parts and supplies from overseas producers (especially but not exclusively China) have been seriously disrupted, and that will have a ripple effect on Canadian production — even assuming we are allowed to go to work in the first place. All that will be enough to produce a serious, but not unusual, recession: a loss of two-four per cent of real GDP, lasting for two-four quarters, driving unemployment up to perhaps eight per cent.

However, if we end up facing a full-out lockdown (as experienced in China or Italy) then the downturn takes on a new order of magnitude. We could see a decline in second-quarter GDP of perhaps 10 per cent (at annualized rates), and an enormous jump in unemployment (well into double digits). In fact, if government statisticians are also on lock-down, we won’t even be able to measure how bad it gets. How soon and how sharply production begins to recover is unknown, depending first and foremost on how quickly people are allowed to begin leaving their homes and resuming normal activity (including working and spending). And if the experience of the “Great Recession” — a decade of slow growth and underutilization that followed the 2008-2009 GFC — is any indication, we would then likely face an extended period of hardship, perhaps lasting another decade.

Another dimension of the crisis could be its potentially dramatic effects on financial stability. It was out of that concern that the announcement today featured all three critical government players (Morneau, Poloz, and Rudin) at the same podium – and why all their announcements were focused on the goal of maintaining credit flows (through emergency lending for small and medium-sized companies, lower interest rates and relaxed credit quality controls). Since the 2008-2009 crisis, the private credit system has behaved in predictably Minskian fashion: first cautious, then (as memories of the meltdown faded) expansive, and finally speculative (entering Minsky’s “Ponzi” phase). This time the debt bubble in the U.S. was concentrated in places other than real estate (the focal point of the 2008-2009 meltdown). Risky (“high-yield”) corporate debt is the most fragile link in the current financial daisy chain: already high-yield bond markets have seen interest rate spreads explode (to seven-eight percentage points above normal corporate lending), and credit is starting to seize up. With many fragile companies, some of them very large, unable to borrow (even for routine or “overnight” purposes) just as their cash flow evaporates from the recession, they will face quick collapse. Other financial weak spots exist in the U.S., too (including credit cards, student debt and some oversold equities).

In Canada, as in 2008-2009, the financial system has been less adventurous and hence is not as fragile. The biggest risk here would be a serious downturn in inflated housing prices (the main legacy of our own debt expansion), with cascading impacts on consumer spending, household financial stress and ultimately the stability of banks and other financial institutions. Stopping that kind of contagion quickly is almost as important to the government, as stopping the spread of the actual virus.

How government should respond

I look forward to working with other progressive economists to imagine and describe a fulsome, comprehensive, ambitious and concrete vision for responding to this crisis. Here are some of the obvious areas:

Immediate Mobilization of Resources to Protect Health: Obviously governments and health authorities must now throw every possible real resource into protecting health, as much as they can, including:

- More staff at health facilities.

- Alternate off-site or mobile testing capacities.

- Home support for people quarantined or recovering at home.

- Quick expansion of capital equipment (including buildings and equipment), as much as possible.

This mobilization will cost many billions of dollars, and constitutes an unfortunate form of “stimulus.”

Income Protection for Workers: The pandemic has exposed a frightening and dangerous aspect of the new precarious labour market. Only about half of employed people now work in a “standard” full-time permanent job with benefits — like sick leave. So when people are instructed to stay home from work to avoid spreading the virus, many incur a major and immediate financial loss. Unfortunately, that will compel some to ignore the health advice and keep working — with catastrophic health consequences. This pandemic is reminding us that the wellbeing of everyone, depends on the wellbeing of everyone else. The short-sighted responses of some business leaders, complaining about the cost of sick leave and that workers “whine” or “fake” their conditions, is as morally repugnant as it is clinically destructive. (For a despicable example, see Howard Levitt’s comments about workers imagining illness on CBC’s The Current).

An obvious place to protect workers whose incomes are being interrupted by the pandemic is through the EI system, but it needs immediate and far-reaching emergency changes (I listed some of these in my recent Toronto Star column):

- Waive the 1-week waiting period for EI (the government has already said it will).

- Waive the qualifying hours requirement for the period of the pandemic (and, of course, it should be fixed long-term anyway).

- Consider special emergency payments (similar to EI’s existing natural disaster provisions).

- Consider special payments to contractors, gig workers and others not normally entitled to EI.

- Accelerate work-sharing arrangements to allow more people to keep their jobs.

In addition to extending EI and other income supports, workers need other protections in the coming period: including waiving requirements to fetch doctors’ notes and other red tape and having full job protection during the pandemic (so their jobs are not at risk for following health advice). All of this highlights the need for big reform in Canada’s existing laws governing sick pay (only Quebec ensures minimum paid sick leave), STD and LTD measures, and job protection. These problems were already glaring; the pandemic has now brought them to everyone’s attention, and reminded everyone that their personal health depends on collective well-being.

Other ways to put spending power directly into the pockets of low- and middle-income Canadians, reducing the financial barriers to staying at home, could include direct one-time payments to all households (as Australia did in 2009, with great success), or more targeted income assistance to reflect and offset the economic impact on more financially vulnerable households. One option in that regard would be to expand and accelerate payments of GST credits and Canada Child Benefit cheques.

Debt Relief: Morneau and his colleagues moved quickly today to assure businesses that they can continue to access credit to maintain operations and stave off bankruptcy. There will likely be a need for more hands-on support for firms in many industries (including airlines and other transportation and tourism providers). It makes sense to keep businesses from going bankrupt at a time when unemployment is rising anyway, but those interventions need to learn from the mistakes of past rescues. Conditions must be attached to protect employees at these firms right through the crisis (like no layoffs), and to ensure that rescued companies are held to long-term performance requirements (including future Canadian production and employment). The memory of major banks and automakers that were bailed out at the public’s expense in 2009, and then quickly returned to their bad old ways (speculative lending and industrial disinvestment, respectively) reminds us to leverage our support during times of crisis into long-run influence over their subsequent activities. The best approach in that regard is to take public equity stakes in these businesses as a condition of financial support (as some European countries did with banks and other major bailed-out businesses).

At the same time, other segments of society also need protection from their creditors, as their ability to work and earn disappears. There should be restrictions placed on foreclosures and evictions (for both homeowners and renters), and deferral periods for personal and credit card debts.

Other Short-Term Fiscal Stimulus: The federal government will need to consider other ways to inject immediate spending power into the economy in its March 30 budget, or earlier. Expanded transfer payments to the provinces for health-related expenses is an obvious option. Other ideas are helpfully catalogued in the annual “Alternative Federal Budget” documents.

Longer-Run Reconstruction: On the assumption that the coming recession is harsh and its after-effects long-lasting, the government will need to play a leading role in the longer-term reconstruction and reorientation of the economy. The traditional tools of stabilization (monetary and fiscal adjustments) are clearly not capable of addressing the scale of the problem. Monetary policy, indeed, has already lost most of its effectiveness: with interest rates near zero, and borrowers scared deeply about what lies ahead, the emergency interest rates cuts announced by the Bank of Canada this week will have virtually no impact on real economic activity in the coming year or longer. (It probably won’t even reignite house price inflation, which has been its dominant “achievement” of late.)

And fiscal interventions will need to go far beyond counter-cyclical stabilization. Canada’s economy will need to rely on public service, public investment and public entrepreneurship as its main “engines” of growth, to recover from the coming downturn, prepare for future health and environmental crises, and improve conditions in our communities. The abysmal failure of private business capital spending in recent years — which has fallen by one-third as a share of GDP since the turn of the century, despite hugely expensive corporate tax cuts — was already indicating a growing role for public investment to lead the way. Now, in this moment, it is laughable to imagine that private capital spending or exports will somehow lead the reconstruction of a national economy that will experience an unprecedented and scarring shock.

There is no shortage of urgent rebuilding required in our economy and our communities: sustainable transit, green energy, non-market housing, expanded public services (including aged care and early child education) and any number of other urgent priorities. The case for mobilizing those resources, under the leadership of governments and other public institutions, is compelling. We can put people to work, repair the damage of this crisis (and better prepare for the next one), and deliver valuable services. All we need is the willingness to imagine a different model of organizing and leading economic activity.

Last nail in coffin of deficit-mania?

Incredibly, Conservatives like Jason Kenney and Pierre Poilievre have still been scare-mongering about deficits, even as the public-health emergency gathered momentum. Kenney in particular should be politically shunned for his incredible decision to attack Alberta’s doctors and rip up their employment contracts (alongside his other attacks on public-health workers) — just as we ask them to risk their lives, to save ours. This tired old deficit-mania will have zero resonance with the public in coming months: they are quite rightly preoccupied with more important things.

Nevertheless, long-standing indoctrination in the ideology of austerity will hold back the government response to the crisis. Mainstream proposals for fiscal stimulus will be too small to make a significant difference. For example, bank economists today are suggesting injections worth one per cent of GDP; that wouldn’t put a dent in the more daunting recession scenarios I described above. It is not unusual for national governments to experience deficits equal to five per cent or more of GDP during severe economic downturns. That works out to $120 billion for the federal government. Anything less than that, and the government is literally not doing its job in trying to protect Canadians from this downturn.

Interest rates, already rock-bottom, have plunged in the last month. The government of Canada can now issue 30-year bonds for well below one per cent annual interest. That is negative in real terms (ie. lower than inflation). So quite literally, the government will save money by borrowing more (paying back less in real terms, after 30 years, than they borrowed) — to say nothing of the economic and social good that would be done by putting that money to work in emergency public projects and services.

Of course, we can and should consider alternative financing mechanisms (like quantitative easing and other methods of directly harnessing public credit institutions to finance public works). That genie was let out of the bottle in the 2008-2009 crisis, but so far has been used in a stinted, one-sided way: using central-bank-created money to purchase financial assets from investors and institutions, in hopes they then spend or lend their excess cash to get the economy moving. A much better approach — perhaps called “people’s quantitative easing”? — would be to use created funds (from the central bank or other public banks) to directly finance needed investments and services, thus putting the new money directly into the projects and people that need it most. That would have much more economic bang for the QE buck. But it would constitute a sacrilege against the traditional property relationships embedded in private credit banking.

A turning point?

Great crises like this are frightening and dangerous. Our economic, social and democratic institutions are still damaged and fraying after 10 long years trying to recover from the last meltdown. Dangerous populist and authoritarian impulses have sprouted from that hardship. Progressives are not sufficiently united, confident and focused on what needs to be done, to turn the tide in our favour.

But a crisis can also be an opportunity. The failure of financialized, neo-liberal capitalism will be laid bare more clearly than ever in coming months. For example, the inability of rich countries (like the U.S.) to provide even rudimentary coordination and communication during a public emergency, resulting in thousands of preventable deaths, starkly highlights the enormous misallocation of human and economic capacity under capitalism, and its inherent and repeating coordination failures. The private sector will definitely be unable to get the economy back on its feet after this crisis. So we need to look elsewhere for economic leadership.

Just as the Second World War “solved” the Great Depression by mobilizing enormous resources in an urgent attempt to meet a huge threat (global fascism), we now need another, peaceful war — a war on poverty, on epidemics and on pollution. And by organizing ourselves as society to fight that war, we will actually make ourselves better off right now: creating jobs and incomes, providing needed care and services, generating taxes. And we will benefit in the long-run by winning those “wars,” and building a safer, sustainable world.

This is the time to develop and advance a progressive vision for a massive, public-led reconstruction agenda. Parts of it already exist, in various forms:

- The “High-Investment Sustainable Full-Employment Economy” I describe in Chapter 28 of my Economics for Everyone.

- The various incarnations of the Green New Deal program that have been proposed in various countries.

- The CCPA’s Alternative Federal Budget.

- The “Jobs You Can Count On” strategy developed by the Australian Council of Trade Unions.

- And many more…

Conservatives and the wealthy they serve never let a crisis go to waste. They follow well the advice of Milton Friedman:

“Only a crisis actual or perceived produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.” (Capitalism and Freedom, 1982, p. xiv)

Naomi Klein showed us how the powerful take advantage of crisis to reinforce their power, even when it was their power that caused the crisis. We gotta know they will try to do the same with this crisis: pushing their well-known agenda of austerity, privatization and inequality into still more frightening and authoritarian directions.

So we desperately need our own courageous, ambitious, holistic alternatives. And if we do a good job educating, organizing and mobilizing around that more hopeful and democratic agenda, then it too can become politically inevitable. That’s the silver lining to this very scary moment.

Jim Stanford is economist and director of the Centre for Future Work, and divides his time between Vancouver and Sydney. The article originally appeared on the Progressive Economics Forum

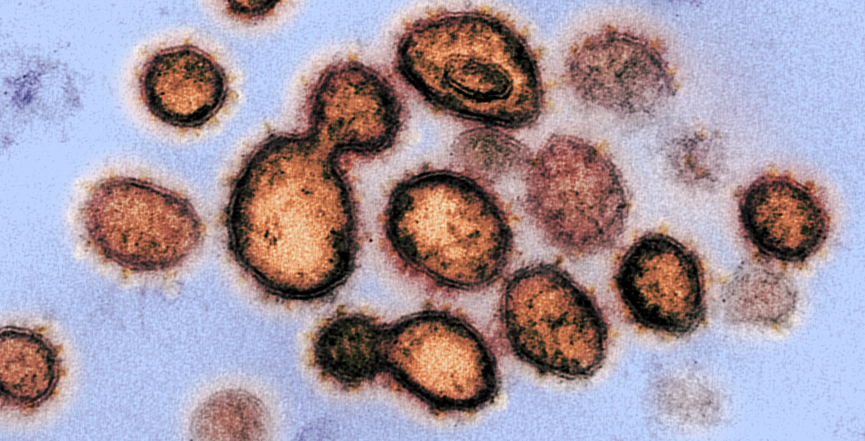

Image: NIAID/Flickr