One day, Kate McQuillen was shopping at her local Home Depot, in the market for a six-inch pipe among other materials she needed for her work. As she made inquiries to an employee, the man looked at her and asked: “Lady, are you making a pipe bomb?”

“On one hand I could say ‘yes,'” says the Chicago-based artist, who finished an MFA in 2009 at Toronto’s York University. “I panicked and ran to the checkout but then, do I pay with cash or with credit? Credit can be traced.”

McQuillen — whose show “Backscatter” (an exploration of surveillance in the wake of 9-11) recently closed at the O’Born Contemporary gallery in Toronto — says in creating her works, she could easily become a terror suspect herself. The items she shopped for at Home Depot were for a pipe bomb — which she re-created by making a porcelain mould of it and then tearing one end, so it had the appearance of having exploded.

“My work is about the climate of suspicion we live in [and] I generally do a lot of research on improvised explosives. I wonder if this is drawing attention to myself — especially in light of Edward Snowden’s revelations.”

McQuillen’s Toronto show dovetailed with Snowden’s plight — the former National Security Agency (NSA) computer contractor who absconded with highly classified information revealing the magnitude of the U.S. government’s mass surveillance program.

However, McQuillen’s “Backscatter” work was actually triggered by stories she read in 2012 about the extent of the U.S. government’s wiretapping program. She was intrigued by its covert nature and the idea that the public “wasn’t really allowed to ask about these things.”

No checks on the NSA’s power

Of Snowden’s whistleblowing, McQuillen says she primarily felt relieved: “I’ve been questioning the freedom of thought and how terrorism is affecting our lives. When the Snowden story broke, I felt less like a conspiracy theorist.”

The artist says the lack of oversight over the NSA’s snooping program worries her.

“There must be some way they can do their job and find the information they need and not sweep up everyone’s information into some haystack they can sort through,” she points out.

“My bigger concern is that there are no checks on the amount of power they have. There’s no discussion of where the lines should be drawn and, we’re entrusting them to look for the right things.”

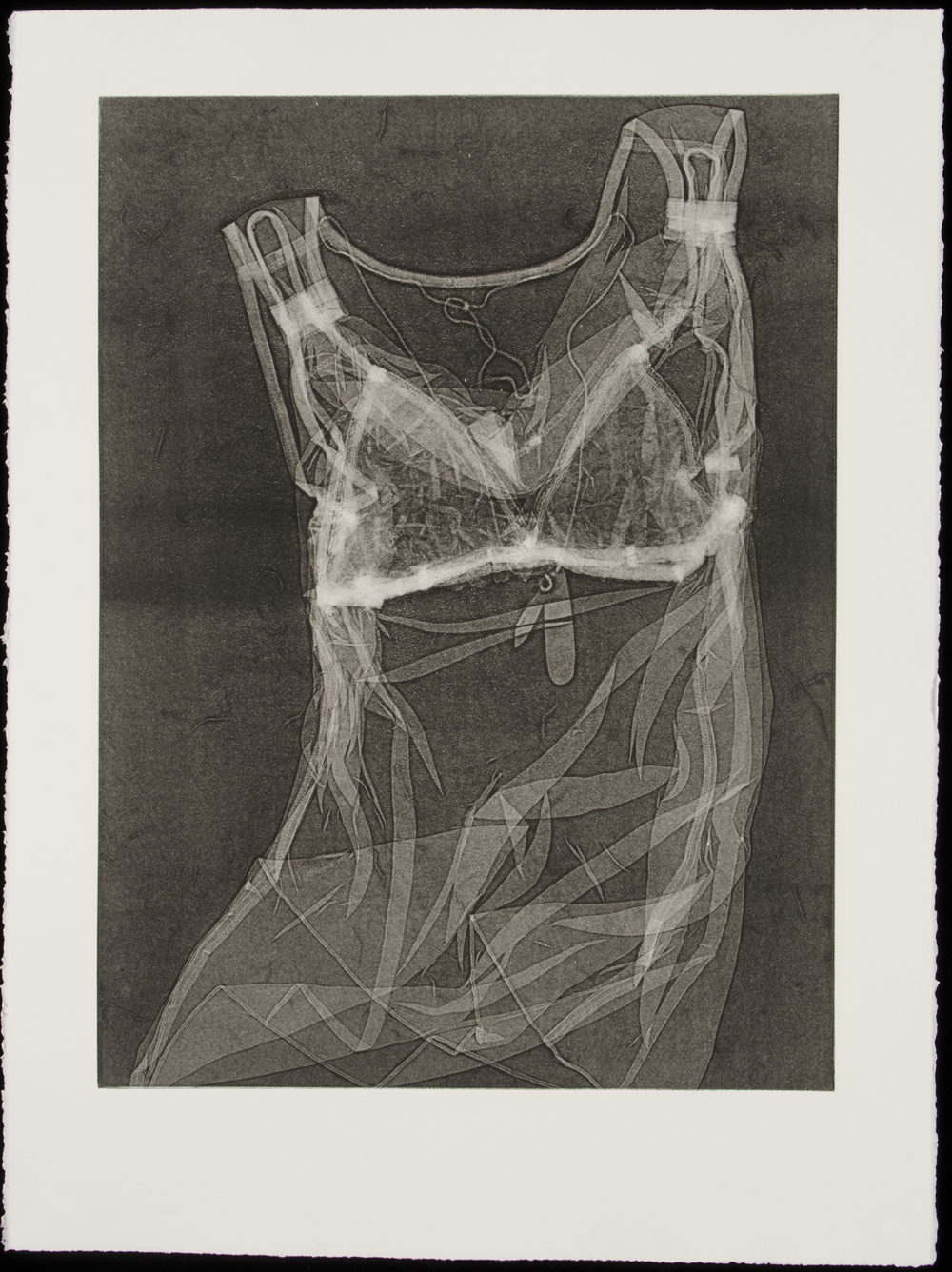

For her “Backscatter” exhibit, McQuillen used a process of pressure printing in which soft objects like clothing could be sent through a printer to produce a kind of X-ray image. She decided to run her clothes and underwear through with cut-out paper images of box cutters, knives and guns “hidden” in the clothing.

“I wanted to produce a body of work about my feelings concerning the extent of being under surveillance. I used my underwear to show the intimacy we’re having with the government,” says McQuillen. “They are seeing more of me than I want. I am a victim of surveillance. I feel vulnerable.”

Analog vs. digital

Other images in the exhibit are in the shape of a human being but created with a composite of squares that resemble UPC codes. These are titled “Backscatter” in reference to the Backscatter X-ray body scan machines. The machine captures the radiation reflecting from a person and forms a 2D image.

“It’s the idea of the data trails we leave behind,” explains McQuillen.

For those works, she uses paint on a plate and runs that through a press in a process called mono printing. First, she uses razor blades to manipulate ink on the surface plate and then prints the image before cutting them into 4×4 inch squares. Lastly, she re-arranges the squares into a form, placing a negative human silhouette cut-out over them.

“Data is compiled to make a portrait of a person. They are using meta-data,” says McQuillen. “I’m doing the same but instead, using real paper and a printing press — which was the original mass disseminator of information as you might recall, i.e. Luther’s bible. It’s analog versus digital.”

McQuillen, who visits Canada often, credits two years at York with informing her practice.

“It made me realize how extreme things had become in the U.S.,” she observes. “Even going to federal buildings in downtown Chicago, you go through security and you have to hand over your electronic devices. These are government buildings which shouldn’t be fearful places. When I go back to Canada, it’s like a sigh of relief to be in a place that’s less crazy.”

This year, however, terrorism became real again in the U.S. with the bombings at the Boston Marathon. It’s McQuillen’s hometown.

“My life has been touched by terrorist events. My first experience of terrorism was actually the 1993 bombing at the World Trade Center. My older brother was working there and it took a few hours to find out if he was OK. In Boston, one of my sister’s friends ended up losing her foot… but she’s has been amazing, she’s doing really well.”

McQuillen says despite having had personal connections to these incidents, she insists on taking a “practical” look at terrorism.

“In this story of terrorism, there have only been a few actual attacks on American soil in the past decade. More than 3,000 people have died in terrorism-related incidents here since 9-11 but you look at gun violence and in Chicago alone, 400 to 500 people die every year. Where are the priorities?”

Some of McQuillen’s work will be featured at O’Born’s booth (#1012) at Art Toronto, running from Oct. 25 to 28, and her pieces are also available through the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Sales and Rentals Department.

If you’re wondering how she purchased her items at Home Depot — she paid with cash.

June Chua is a Toronto-based journalist who regularly writes about the arts for rabble.ca.

Images: Kate McQuillen/O’Born Contemporary