Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

In the past few months we’ve heard the term “machine learning” bandied about by Google execs, computer scientists and nerdish blowhards at pool parties. The phrase is used to explain why digital assistants like Google Now and Siri have gotten so much better at understanding what we mean, why Google Photos can find images of flowers so well and how even our watches seem to listen better than an average 14-year-old.

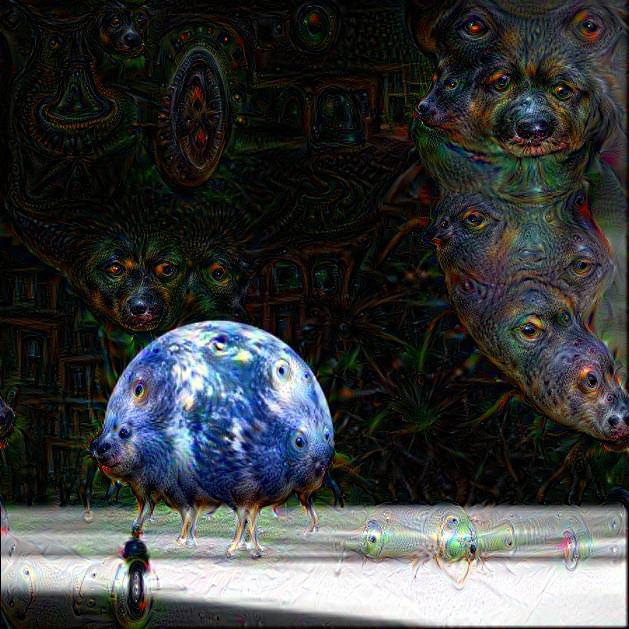

Plus, the terms have been in the news. Last month social media sites were atwitter with pictures generated by Google’s “Deep Dream” neural network. The images, actually iterated versions of abstract images from a high level in the neural network, looked like Salvador Dali’s bad acid trips.

And, last week came news that a cute little robot had achieved a kind of self-awareness by passing (in a fashion) an induction puzzle called the “King’s Wisemen” test. In both cases, it seemed, machines were starting to imagine the world and their place in it as if they were human.

But what is machine learning, exactly?

At a very simple level, pattern recognition. Machine learning allows computers to understand all sorts of patterns. And, pattern recognition is something humans are good at and computers have been historically terrible at. Pit a computer against a human in a cube-root calculating contest and the human will be buying the drinks. But, ask a human and a computer to sort pictures of cats from pictures of not-cats and it will be the circuitry picking up the tab. Machine learning is levelling the playing field.

Humans see stories, patterns, faces and archetypes everywhere. They help us filter our world. Until recently, computers have had very little exposure to the real world and so couldn’t make sense of it. But modern neural networks fed a steady diet of real-world images can help machines sort out one kind of image from another. Artificial neural networks work much the way our brains do when we try to sort out what we see and hear. Think of neural networks as layers of abstraction each talking to the others and each with a specific task. The first layer of a neural network might be good at hunting for the edges of things. All it knows is that one thing in a photo has ended and another has begun. It will be up to further levels to take that input and interpret shape and finally object. Neural networks need to be trained and tweaked so that they learn what a banana is and isn’t. Or that a banana doesn’t always have to appear in a bowl, or beside an orange. Given enough varied images of bananas, a network can then learn to recognize the fruit in a variety of photos, or videos. That doesn’t mean it understands “banananess,” just how to recognize a banana in a picture. The word banana is just a label to it. It knows nothing about slipping on it, the taste, how it is used in smoothies, how it can be used as a joke telephone, etc.

The zany nightmare images that made the social media rounds last month were repeated iterations of one layer of the visual neural network feeding on its own input, making wilder interpretations of shapes based on what it was trained to look for. Despite the chatter about it, it did not mean that androids dream of electric sheep or in any way have such abstract processes going on.

The little self-aware robot is a bit different. In the test, each of three robots was tapped on the head. They were “told” the tap meant that they could not speak, but one tap was essentially a placebo. The robots were then asked “who got tapped so they couldn’t speak.” If all the robots could speak, they all would have answered, “I don’t know.” But, when only one robot could answer, it stood and said “I don’t know.” Then, realizing it was the only one that spoke, corrected itself and said it was not made mute. In other words, it heard itself speak and had related that back to the question. Then it had deduced the solution and was able to identify itself as being unique and apart from its two fellow robots. There’s no doubt the little robot was clever in a very constrained test, but it doesn’t mean machines have become sentient. Good first step though, little robot.

Both items show the strides machine learning has taken in the last while. Which is good news because artificial intelligence research has been stalled for decades. These breakthroughs may mean that self-aware robots that can laugh when another robot slips on a banana peel are just around the corner. Which is, of course, is a boon to humanity.

Listen to an audio version of this column, read by the author, here.

Wayne MacPhail has been a print and online journalist for 25 years, and is a longtime writer for rabble.ca on technology and the Internet.

Photo: PhOtOnQuAnTiQuE/flickr

Chip in to keep stories like these coming.